Transportation Utility Fees: Possibilities for the City of Milwaukee

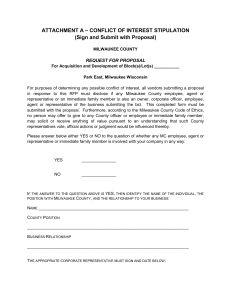

advertisement