In Rem Foreclosures in the City of Milwaukee

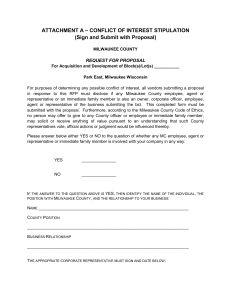

advertisement