Process, Statistical, and Comparative Analysis of Routine Claims for Damages against

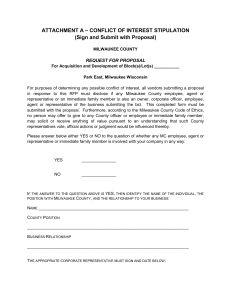

advertisement