Milwaukee’s Community Development Block Grant Connecting Youth Services and Economic Development

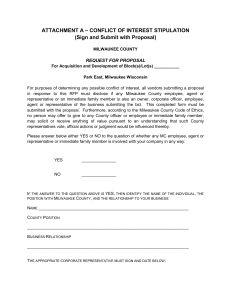

advertisement