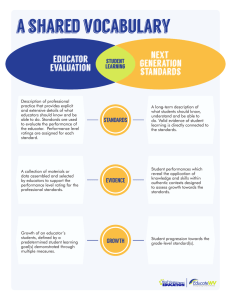

Evaluation Plan for Wisconsin’s Educator Effectiveness System

advertisement