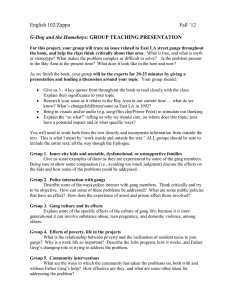

Community Case Studies

advertisement