Analysis of English Language Achievement Among Wisconsin English Language Learners

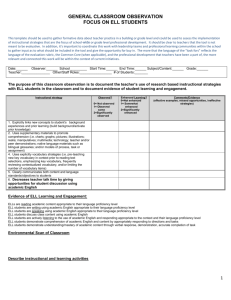

advertisement