Integrating Knowledge Management Technologies in Organizational Business Processes: Real

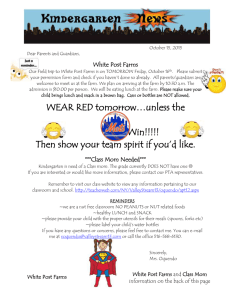

advertisement