S E R

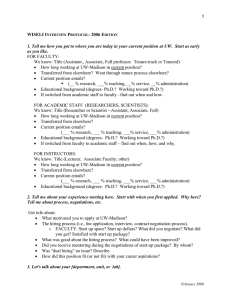

advertisement