BIRTHING AN EPISTEMOLOGICAL SHIFT: THE DISCURSIVE FUNCTION OF EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY OBSTETRICS MANUALS

advertisement

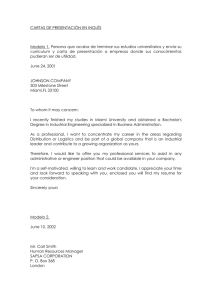

DIECIOCHO 39.1 (Spring 2016) 83 BIRTHING AN EPISTEMOLOGICAL SHIFT: THE DISCURSIVE FUNCTION OF EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY OBSTETRICS MANUALS RHI JOHNSON University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill “Conviene que sepas lo que haces. Ese seno que vas a abrir encierra no un ser humano, no una criatura, sino «una verdad». Fíjate bien. Te lo advierto. ¿Sabes lo que es «una verdad»? Una fiera suelta que puede acabar con nosotros, y acaso con el mundo. ¿Te atreves, ¡oh comadrón heroico!, a sacar a luz «una verdad»?” (Emilia Pardo Bazán: “El Comadrón,” 1901) Volume 39.1 Spring, 2016 The University of Virginia “Luego la criatura se halla en su cabal madurez, incitada de la hambre, y de la necesidad de respirar, y no cabiendo comodamente en la estrechéz de la matriz, inclina la cabeza ácia su orificio, y haciendo para hallar su salida varios movimientos, irrita las membranas del útero, y demás partes sensitivas, produciendo los grandes dolores, que son causa de que todas las partes se vayan relaxando, y contribuyendo á la expulsión.” (Antonio Medina, 1750) Antonio Medina’s suggestion that birth occurs when a fetus gets hungry and starts head-butting the uterus may seem strange, a nightmarish scenario more at home in Ridley Scott’s 1979 Alien than in an obstetrics textbook, but if truths can be birthed, why then should they not take such a text for their womb? 1 The didactic texts of the eighteenth century, like Pardo Bazán’s departed mother, held truths within them, truths that played on the same fears that her story does: about the womb, female power, and the unknown. These texts not only contain the hard cold truths of medicine, but also formed the proving grounds for a host of philosophical ideas. In the textual creation of the midwife in eighteenth century obstetrical manuals, in the turmoil of the medical hierarchy, there is evidence not only of the misogynist power structure that has already been recognized in the period, but of a clash of epistemologies: between classical training, the veracity of which was being called into question, and previously denigrated empirical traditions, the revaluation of which formed the basis of educational reforms throughout the century. This essay 1 Recent research by URI’s Holly Dunsworth has brought into question the “obstetric dilemma” that, for decades, has suggested that the ratio of pelvis to skull size limits gestation. She credits instead the mother’s metabolic ceiling, or highest sustainable basal metabolic rate (Wayman). While fetal agency is absent, birth does happen, in a way, because the fetus gets hungry! 84 Johnson, "Eighteenth-Century Obstetrics Manuals" examines the philosophical discourse that exists alongside the scientific content of physician Antonio Medina’s Cartilla nueva util y necesaria para instruirse las matronas que vulgarmente se llaman Comadres en el oficio de Partear (1750), and fellow medical practitioner Juan de Navas's Elementos del arte de Partear (1798),2 as well as in Benito Jerónimo Feijoo’s published letter “Uso más honesto de la arte Obstetricia” (1747). These texts have been treated to an extreme paucity of literary analyses to date. This lack, perhaps owing to their supposed utilitarian function, is ill conceived, since that focus on usefulness is, in itself, a key element of the philosophy of Spain’s enlightenment reformers. This led to the inclusion of much sociological and philosophical discourse within texts that hold utility as their main function.3 It is this peripheral content that this essay examines, focusing on authorial asides, explanatory material, and choices of diction, as well as threads that tie the three texts together. The earliest of the three texts that I examine, Feijoo’s letter, which was included in the second tome of his Cartas curiosas y eruditas (1747), offers entry to the state of social discourse on the male versus female midwife, in its bureaucratic, systemic, and social contexts, at the outset of attempted reforms. 4 This letter’s consequence, and the weight of Feijoo’s voice, can be seen in the publication of Medina’s book three years later, at the behest of the Protomedicato, to serve as the instructional manual for the licensure examinations of midwives, which were established in the same year (Usandizaga 238).5 Though this book is brief and intentionally focused on the most basic elements and techniques of the trade, its philosophical discourse suggests a beginning to an epistemological shift in the medical establishment, in the face of great social need, and the eighteenth-century’s rapid modernization of surgical and medical practices. Navas’s Elementos del arte de Partear, published at the end of the century, is the more scientifically accurate of two contemporaneous texts that present the state of obstetrical 2 Citations in this text come from an 1815 reprint. The Spanish Enlightenment was not a movement of the populace, but rather one of the liberal-minded subset of the elite, struggling against a more conservative populous. These ilustrados, inheritors of the reformist attitude of the preenlightenment novatores and supported by the new Bourbon dynasty, pushed for public utilitarian education, empirical modes of study in the sciences, and the questioning of knowledge and beliefs supported only by tradition or Church dogma. For a background on the movement, see Deacon. 3 4 While this letter is frequently mentioned in medical histories, it has not been the object of extended study to date. For background on the author, see McClelland. 5 The Protomedicato is the regulatory body that had sole jurisdiction throughout the period in respect to the regulation of physicians, surgeons, apothecaries, and all such persons as were engaged in healing (Granjel 92). DIECIOCHO 39.1 (Spring 2016) 85 knowledge at the time (Granjel 224). While the text is composed of two large tomes, detailing anatomy and procedures, I focus on the author’s history of obstetrics and commentary on the state of the field, which form the introduction to the text. It is there that Navas’s contribution to the birth of a socio-scientific truth is most clearly visible. To give an example of the breadth of his work, see the first of four pages of the table of contents of the first volume (Figure 1). Figure 1. Don José de Navas, Elementos del Arte de Partear (Madrid: Imprenta de Sancha, 1815) When Feijoo published his letter, as Michael Burke discusses in his history of the Royal College of Surgery at San Carlos (1975), Spain’s university programs for medical education were so steeped in solipsism, so firmly entrenched in the study of Hippocratic disease theories and Aristotelian metaphysics, and so distanced from actual patients or cadavers, that one could be licensed a physician without ever having dissected a body (23). While the early seventeenth century had seen Spain’s physicians among the best in Europe, that grandeur, if not the pride associated with it, had long since fallen away. In 1625, the medical faculty at the University of 86 Johnson, "Eighteenth-Century Obstetrics Manuals" Salamanca restored Galen in place of Vesalius, and enacted no further academic changes until 1770 (45). Yet these university-trained physicians, the only medical branch based in extended, institutional study, held the highest socioeconomic position of any healer, and looked down on other providers: surgeons, barber/bloodletters, and midwives, all of whom were trained empirically by apprenticeship and who honed their skills through practice rather than theory (Usandizaga 227). Yet, even at the height of this stratification of power, the medical elite, the power behind the university system, realized that a lay surgeon knew more anatomy than a universityeducated physician (Burke 47). This dichotomy between prestigious training and practical skill, along with medicine’s contact with both classical theory and the natural sciences, is in part responsible for the fact that medical texts are a useful vehicle for the discussion of the societal exigencies that confronted efforts at reform. Indeed, the practice of medicine was seen as representative of the general shortcomings of Spanish science by Feijoo and the ilustrados (Burke 16-17). Crucial for this essay is that through their engagement with the overarching state of medical education, these texts position the female provider in terms of the male hegemony and the problems of access that cement the her as a crucial player in the medical field. What is more, public health reform not only had the potential to be visible, but also to be immediately beneficial to a population that was generally conservative and uncomfortable with the very idea of systemic change (17). Spain’s populace, the seemingly immovable object against which the ilustrados thrust their ideas, is key in entering into any text of Feijoo’s that is aimed at a public audience (whether explicitly, or behind a direct address to an anonymous patron).6 Feijoo stated, with all plainness, the disdain that he held for his public. In “La voz del pueblo,” he asserted that “el valor de las opiniones se ha de computar por el peso, no el número” (1). Nor were intellectual circles free from his critique of common thought, as he held that educated persons were just as likely to deny the usefulness of new knowledge, in an attempt to maintain their status (Burke 6). Even in the first paragraph of “Uso mas honesto de la arte Obstetricia,” Feijoo reiterates his disgust for his readership through a rhetorical question asked of his imagined sole reader: “Pero, señor mío, ¿qué puedo yo en esta materia decir al Público, que el mismo Público ignore?” (235). Because of this desire and repeated intention to dispel long-held but problematic social and academic notions, it becomes useful to discuss not only Feijoo’s message, but also his rhetorical strategies. Critical treatment of “Uso mas honesto de la arte Obstetricia” has assumed that it is supportive of male midwives and surgically trained birth attendants who were entering the traditionally female sphere of the birthing 6 For a study of this eighteenth century public, see Medina Domínguez. DIECIOCHO 39.1 (Spring 2016) 87 chamber in unforeseen numbers, and that the letter and its writer opposed the practice of the female midwife.7 In his Historia de la Obstetricia y de la Ginecología en España, M. Usandizaga references Feijoo’s letter as one of support for the dominance of male practitioners: “defendiendo la intervención de los hombres por más competentes y más capaces” (215). Nevertheless, I claim that this assumption of a misogynist narrative in Feijoo’s letter only makes sense in a reading of its surface level criticism. As the most blatant example of such criticism of the female practitioner, Feijoo says “[l]as mugeres son ignorantíssimas del Arte, que para él se requiere. Mil lamentables casos están descubriendo cada día sus errores” (235). The shortsightedness of a valorization of the letter that looks no further than this open critique of female providers is key to understanding both his message and the social state at the time of his writing.8 While it is hedged in with this kind of anti-midwife rhetoric, the main thrust of the letter is stated clearly: “Mas si se pudiese tomar providencia para que las mujeres se instruyesen bien en este Arte, deberían ser excluidos enteramente de su ejercicio los hombres. ¿Y se podía tomar esta providencia? Sin duda” (237). In this statement not only is Feijoo’s premise clear: that female care providers should be educated and have sole providence in the field, but it is also possible to perceive Feijoo’s means of convincing his public of the merit of his position. In that attempt at persuasion, it is possible to see the function of his indemnifications of female competence. To this end, Feijoo utilizes the social anxieties and prejudices of his readership. He suggests the impropriety of the male provider’s access to the female body by emphasizing female modesty as more important than life itself: “puede una mujer sacrificar la vida a la honestidad, cuando constituida en una enfermedad, que sólo es curable exponiendo a las manos, y a los ojos de un hombre lo que más esconde el honor, le es esto, o igualmente, o más sensible que la muerte” (236). Not only is it appropriate for a woman to choose death over the touch of a man not her husband, it is the moral decision: “que más quería morir, que usar del ministerio del Cirujano; bien que tuvo la dicha de que una mujer le suplió, a quien acaso Dios con especial providencia dirigió la mano, por premiar aquel acto de pureza heroica” (236). Feijoo carries this created modesty to an extreme, in that “cuando llega el caso de ponerlas por algún delito grave en la tortura, 7 Male purview in the birthing chamber can be marked as entering Spain in 1713, when the birth of Queen Luisa Gabriela de Saboya’s child was attended by a male surgeon (Pardo Tomás and Martínez Vidal 49). Pardo Tomás and Martínez Vidal, in “The Ignorance of Midwives: The Role of Clergymen in Spanish Enlightenment Debates on Birth Care,” explore the temporary nature of Feijoo’s support of male attendants, but do not discuss the persuasive function of his use of anti-midwife rhetoric. 8 88 Johnson, "Eighteenth-Century Obstetrics Manuals" sienten más la desnudez, que los cordeles” (237). This clearly hyperbolic construction illustrates the intentionally ironic seriousness with which he treats the topic. The only element described in this letter that makes the death of a woman in labor problematic, thereby validating the existence of the field of obstetrics, falls fortuitously in line with one of the most intense social fears of Feijoo’s deeply religious audience: limbo. This is visible in how he differentiates death by disease from death by childbed: “en el primero sólo insta la conservación de la propia vida, y en el segundo también el salvamento, así eterno, como temporal del feto” (237). Through these two messages, Feijoo sets up a rational argument against the male midwife: women are right to prefer death to the touch of a male surgeon, but it is immoral to choose death when the life and soul of a fetus are at risk. He continues, sweetening the rational answer for his readers by appealing to the stereotypes and prejudices that he assumes them to hold.9 This is evidenced by the letter’s final sentiment, which reiterates his solution, while corroborating a negative social perception: La debilidad, o poca fuerza de las mujeres es patente a todo el mundo. […] Pero no hay experiencia alguna de que las mujeres sean ineptas para el uso de la Cirugía. Y en fin, sea lo que fuere de la Cirugía tomada en toda su extensión; para la particular obra de facilitar el puerperio, supuesta igual enseñanza, no veo por dónde se pueda asignar a los hombres alguna mayor disposición que a las mujeres. (240) Allowing women access to medical training and making them licensed providers, especially if their purview is restricted to the ills of women, does not have to destroy the opinion of women held by his readership -that women are both weak and stupid.10 This assumption of prejudice should not, however, be read as representative of Feijoo’s own opinion. While his argument allows his readers to hold to their beliefs, these popuarly accepted products of the collective consciousness, like inherent female weakness, are the type of sentiment that Feijoo and other reformers, in the tradition of 9 An analysis of Feijoo’s discussion of the mother’s and midwife’s role in both life and birth could counter the contention that “Uso más honesto de la arte Obstetricia” deviates strongly from his argument in “Defensa de las mujeres,” but lies outside the scope of this essay. 10 This use of social and religious angst to create a persuasive argument in a scientific discourse finds a deeper theoretical basis in Paul Ilie’s discussion of epistemological belief in the context of the enlightenment as a system of connections dependent on cohesion of ideas, whether rationally or dogmatically based. This idea allows, in this instance, the application of a religious or social rationalization to form part of a scientific belief system (40). DIECIOCHO 39.1 (Spring 2016) 89 the novatores, fought against, and are what led to his low opinion of his readership. And yet, the idea of opposition to female practice arises not only in discussion of Feijoo’s letter, but also in the little critical attention has been paid to the eighteenth century Spanish midwife. Teresa Ortiz, in “From Hegemony to Subordination: Midwives in Early Modern Spain” (1993), constructs the shifting educational and professional systems of the medical field around the displacement of the female provider, saying: “the educational reforms reduced their autonomy and relegated them scientifically and professionally during a lengthy process which lasted throughout the century” (100). It is easy to see, as she does, the entry of men into a traditionally female sphere as solely that: an invasion.11 There is, however, another facet to this surge in male practitioners that merits mention. While the evolution of surgery in the eighteenth century sent men into obstetrics in large numbers for the first time, they did so, in large part, because of the development of new practices that had the potential to (and did) save many lives. Surgical advances leading to the performance of successful Cesarean sections on living women,12 the symphysiotomy,13 and the development of forceps, all allowed for successful deliveries where This is the angle that Enrique Fernández followed in his article “Tres testimonios del control y desplazamiento de las comadronas en españa (Siglos XIII al XVII)” (2007). where he bases his discussion of gender dynamics off of Ortiz’s, saying “los estudios existentes […] confirman esta tendencia general al desplazamiento y control de las comadronas” (91). Yet one of the three works that he discusses suggests the social merit of the practice of midwifery even by noble women, which forces him to conclude that “es evidente que la historia de este desplazamiento es compleja y no se puede reducir simplemente a una narrativa lineal” (99). 11 12 Post-mortem Cesarean sections and the in utero dismemberment and removal of dead fetuses had existed for centuries, and in the 15th to 17th centuries are recorded as the purview of midwives, but the development of techniques that made in vitu Cesareans possible was an 18th century advance, and required different and more advanced skills than the excision of a fetus from a corpse. These techniques were a point of great contention during the century, with some practitioners denying the viability of the operation in vitu until the 1770’s (Usandizaga 242-3). 13 A symphysiotomy is an operation that, by cutting the cartilage at the pubic symphysis, can widen the opening of the pelvis by up to 2.5 cm. This can make a birth possible in the event of a bony obstruction, where the pelvic opening is of a smaller diameter than the head of the fetus. While a symphysiotomy can lead to a successful birth, it is an operation from which a full recovery is unlikely, as cartilage does not easily regrow. It also has very high maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality rates. This high risk, along with advances in Cesarean sections, has made the procedure relatively obsolete in today’s world, though it is still performed in rare cases where a Cesarean is impossible (Cunningham 544, 567). 90 Johnson, "Eighteenth-Century Obstetrics Manuals" previously a fetus would have died and been removed from the womb in pieces. Advances such as these created an atmosphere where obstructed labors, ectopic pregnancies, retained placenta, dangerous fetal presentation, and other complications no longer spelled a certain death sentence for woman and child (Usandizaga 241-5). These new techniques, however, did not arise from the tradition of midwifery, which is based on assisting nature, rather than intervention (Pardo Tomás and Martínez Vidal 49). The new practices and technologies developed instead in the surgical field, and, in concert with its growing scholastic presence, expanded it, bringing it into contact with midwifery. This contact was not simply a matter of the appropriation by surgeons of the existing practices of the midwife, but rather the development of new skillsets, that were able to ameliorate the high loss of life that has always been a part of birth. Given the correlation between the development of new techniques and the growth of surgery’s influence, the application of a purely misogynist narrative to the period becomes problematic. Midwives were expected to defer to surgeons in complicated cases, but there exists a conflation of educational sexism and professional marginalization in arguments, like Ortiz’s, that assume that these regulations were designed to make midwives “withdraw from some of the duties that they had carried out in the previous century, in order to hand them over to surgeons” (102). It is true, as she discusses, that women’s education was not equal to men’s, but that difference does not mean that surgeons’ entry into obstetrics was designed to excise women. There is one other crucial element in discussing the narrative of the disenfranchisement of the female practitioner, particularly in this narrative’s reliance on an ethos of competition between midwives and medical men throughout the eighteenth century, an idea borrowed from English and French experience and often mistakenly assumed to apply to the Spanish as well (Fernández 91).14 Eighteenth century Spain suffered from a dearth of medical providers, even including practitioners other than physicians, who were unregulated through the first half of the century (Burke 24-25). Granjel’s history of Spanish medicine reveals the extent of this problem. At the end of the century, after a long period of growth in the numbers of physicians and surgeons, there was only one surgeon or physician for every eight hundred inhabitants of a rapidly growing Spain. Furthermore, most of those professionals were concentrated in urban centers, which left the majority of Spain’s population with no access to university-trained practitioners (79). This great need is reflected also in Antonio Orozco Acuaviva’s work on Italian influence in the period, which suggests that “ante la falta de profesionales en el último período de la España de los 14 For a description of the correlative experience of the English midwife, see King (Midwifery chapter 2), Donnison, Achterberg, and Marland. For France, see Sheridan, Gélis, and Marland. DIECIOCHO 39.1 (Spring 2016) 91 Asturias, Felipe V ha de contratar médicos extranjeros para sus ejércitos, Armada y para la propia Casa Real” (192). This need to import providers to serve the portions of society otherwise most likely to have access to care is another strike against the idea of direct and widespread competition between midwives and male providers. In regard to the profession of midwifery at this time, Spanish dynamics are different from those of France and England, and a reassessment of the sort that I develop here is necessary in order to have a more exact understanding of the period in the peninsula. Nor did the midwife exist only outside of the university system. The need for providers throughout the century played strongly into the regulations and systems of licensure that developed around the practice of medicine. Even at the end of the century, when most critics assume that the midwife was on the verge of extinction (Usandizaga 277, Ortiz 95, Fernández 2), Spain’s continued need was recognized, and is evidenced by the Protomedicato’s continued amendment of the requirements that it demanded of midwives as well as surgeons and physicians (Burke 29, 158; Granjel 93), from the reenactment of licensure in 1750 and throughout the second half of the century. When Fernando VI passed the law that made examination of midwives possible, he explained that the poor state of the art required a re-institution of previously suspended requirements: “El Tribunal del Protomedicato me ha hecho presente […] muchos malos sucesos en los partos, provenidos de las mugeres llamadas parteras, y de algunos hombres […]; dimanando este universal perjuicio de haberse suspendido el examen que antes se hacía de las referidas parteras por los Protomédicos” (cited in Burke 216). From that time, guidelines regarding the demonstration and acquisition of requisite skills only increased in rigor. Spain’s protracted need for caregivers should be taken into account when reading texts that suggest problems in the preparation or value of subsets of the medical population. While, as Ortiz suggests, physicians held a bad opinion of midwives because “‘the midwives’ craft is a science or a craft to work with one’s hands” (96), the disinterest verging on disgust that physicians displayed towards midwives exceeded the bounds of a gender binary. The struggle was also based on methodologies of education and professional preparation. Surgeons bore the black mark of the same opinion from physicians throughout most of the century, while surgery grew from a horror show of field amputations and bloody screaming death to something more recognizable as the art that carries the name today. This rift between branches is rooted in the physicians’ inheritance of their art from the classical tradition, in contrast with surgeons’ empirical training. “The physician was a professional, familiar with the classics, and possessing an academic degree; the surgeon, on the other hand, was an uneducated craftsman who worked with his hands” [emphasis added] (Burke 25). This divide between craft and profession discussed in reference to both the midwife and the surgeon was, in fact, the focus of social upheaval. 92 Johnson, "Eighteenth-Century Obstetrics Manuals" As surgical faculties developed in universities, physicians saw themselves losing their status as the sole class of university-trained medical provider, and lay surgeons came into conflict with those who had undergone university training (30). Even before the inclusion of the surgeon in the university faculties, the dichotomy between craft and profession was problematic, because differences in education were not necessarily qualitative. Surgeons and lay practitioners, like midwives, often had a great deal more practical experience than classically trained physicians, which tended to leave these lay practitioner more open to innovation, and less focused on outdated dogmas (Burke 25). Therefore, the threat that came from the inclusion of surgery in university medical systems was not only a threat to the social power and prestige held by the physician, but also a challenge to the epistemological worldview that created him. We can, consequently, describe the conflict between physicians and midwives as indicative not only of a misogynist power structure, but also of the clash of epistemologies that appears in the institutional aversion to surgeons (male). The classical example Feijoo uses in “Uso más honesto” allows a point of entry into the representation of this clash of epistemologies through a social and linguistic gendering of power. This example is the tale of Agnodice, an Athenian girl who supposedly practiced medicine in the fourth century BCE. Although it is unknown if her story is historically true, it is mythic in discourses on female medical practice from the Renaissance onwards (King “Agnodice”). Through the retellings of the same story in both Medina’s and Navas’s texts, it brings us into dialogue with those works. This recurrence of the myth gives entry not only to the meshing of literary and scientific discourses that is intrinsic to the era and the basis of a revalorization of these medical texts, but also hints at the intersectionality that formed the heart of Enlightenment cultural expression. The story, which each of our authors fits his own philosophical ends, is that Agnodice, living in a time when Athens disallowed female physicians, dressed as a man and learned obstetrics clandestinely.15 After she began practicing, because she would tell her clients her sex, she became so popular that the other doctors brought her to trial for misconduct. This trial made it licit for women to practice midwifery. Feijoo not only builds his narrative entirely around Agnodice and other female wielders of agency, but also suggests that in the medical field she is as capable as any man. He goes so far as to excise almost all ascription of positive action to male authority figures. Although Agnodice studies under a physician, the way that he describes her education suggests that she is selftaught: “para cuyo efecto, vistiéndose de hombre, fue a ponerse en la 15 This historical referent signals the potential mendacity of the source material, Higinius’s history, as no known point in Athenian history matches with his description (King “Agnodice”). DIECIOCHO 39.1 (Spring 2016) 93 Escuela de un Médico, llamado Hierófilo, de quien no era conocida. En efecto se instruyó muy bien en la Medicina; y con especialidad en el Arte de Obstetricar” (237). Feijoo’s use of a reflexive construction of the verbs “to put” “to instruct” places the agency of education on the student, rather than the teacher. Agnodice’s practice, once established, is not solely an obstetrical one, though it is comprised only of women: “se puso a ejercer su habilidad en Atenas, siempre disfrazada con el hábito de hombre, asistiendo a las mujeres, no sólo en los partos, mas en cualquiera dolencias, aunque declarándoles en secreto su sexo, por apartar el estorbo de su pudor” [emphasis added] (237). Not only do the verbs here continue to build Agnodice as the creator of her fate, the language places her on par with male physicians, rather than allowing her only enough proficiency to guide births. This creation of a masculine persona for Agnodice draws on the tradition of Spanish Baroque drama, and its trope of the mujer en hábito de hombre or cross-dressing female character, which was enough of a staple of seventeenth century comedia that its convention of credibility increases Agnodice’s transgression: male dress is enough to create the sex, thereby allowing her access to the privileges of the male population as well as a male profession.16 The description of the accusations that come against Agnodice cements the idea of social equality, but also plays on the fears of Feijoo’s contemporaries to suggest the value of female health care providers, without having to state such a position outright. By accusing his Agnodice of sleeping (as a man) with her/his clients, he suggests this as a possible outcome of having a male practitioner, while shielding himself from The Spanish mujer en hábito de hombre was often an intentional and morally justifiable invasion of the sphere of male influence (McKendrick 162), and should not be confused with the English ‘breeches-role,’ where the focus of the crossdressing is on the scintillating view of female ankles (Howe 56). The convention of credibility that Feijoo makes use of also comes from the comedia. Even the most delicate of women, in the dress of a man, would be believed to be male. For example, in the first act of Calderón’s La vida es sueño, Rosaura’s garb not only fools the half-wild Segismundo, it also convinces her unknown father that she is his long lost son: “¡Qué suerte tan inconstante! / Éste es mi hijo, y las señas dicen bien con las señales / del corazón” (I, 412-15). Rosaura’s true sex is only revealed when it is only her female honor that her ex-lover could have damaged. Nor did the inherent believability of such a cross-dressing decrease with time, as is visible in el Duque de Rivas’s nineteenth century Leonor, the fragile heroine of La fuerza del sino. After several minutes of speaking with a priest, while in male dress, and after refusing to enter a cloister: something that for a man suggests excommunication, but that for a woman is the most moral choice, she reveals herself to him: “Doña Leonor: (Muy abatida): Soy una infeliz mujer” (II, 522). To this shocking revelation, the priest responds: “Padre Guardián (Asustado): ¡Una mujer!... ¡Santo cielo! / ¡Una mujer!... A estas horas / en este sitio…¿Qué es esto?” (II, 523-5). Men’s clothing in itself makes for the male character, and an assumption of the prerogatives of masculinity. 16 94 Johnson, "Eighteenth-Century Obstetrics Manuals" rebuttal against that sentiment by putting it not only in someone else’s words, but in a male, powerful, and plural someone else. It was the physicians of the city who “se conjuraron contra ella; y como estaban en la persuasión que era hombre, la acusaron en el Areópago de ilícitas intimidades con el otro sexo; añadiendo, que muchas mujeres se quejaban de dolencias, que no padecían buscando este pretexto para lograr su torpe comercio, con el lampiño Mediquito” (237). This suggestion that a male (but not really) physician might have illicit contact with his patients is exactly the kind of unnatural and unacceptable contact that formed Church and social opposition to the practice of male midwives, until fear of professional females overwhelmed that previous discomfort. That this accusation comes from a group of socially powerful males, who, as representatives of the Athenian power structure, are opposed to female midwives, puts that corollary on Feijoo’s readership. This identification in turn leads his readers down the path toward acceptance of the safety of female birth attendants. The trial itself forms a final point of support for the female voice in matters of women’s health, in that the agency behind the decision that opens the practice of medicine in Athens is female: “Pero sabedoras del caso las Damas Atenienses, intervinieron en la causa, e hicieron tanto, que lograron se abrogase aquella ley; con que quedó triunfante Agnodice, y se declaró a las mujeres el derecho de ejercer el Arte, que ella ejercía” (238). Not only are the women of the city suggested as the group that swayed the verdict, and not only does Agnodice stand triumphant, there is no direct mention of the governing body that overturned the law. The passive construction that allows for the victory leaves the women as the only active participants, apart from the physicians, who, though they represent the readers of the “Uso más honesto,” lose. When Medina takes up this same myth three years later in his Cartilla nueva y útil, and Navas, in Elementos del arte de Partear, the constructions of gendered power dynamics offered (exhibited through means of education, field of practice, and the power breakdown in the court) shift radically from Feijoo’s representation. Medina’s recounting of the tale, while brief, is no less important in its demonstration of his overarching message. As he tells it, “Agnodice fue acusada porque exercía el oficio de Partear en trage de hombre, y que declarado su sexo resolvió el Senado de Atenas, que este útil oficio solo fuese permitido á las Mugeres” (iv). While some of the differences, such as the lack of discussion of Agnodice’s education, can be attributed to the brevity of the telling, the power structure in his version is substantially different.17 The privileges that Agnodice wins, while following a similar didactic course to Feijoo’s, in that they suggest that women can equal men in obstetrical practice, construct a different solution for the gendering of power in the art. The office that Agnodice wins is more 17 Though his Agnodice is not named an auto-didact, the very title of his book uses the same reflexive construction as Feijoo’s recounting of the myth. DIECIOCHO 39.1 (Spring 2016) 95 limited: midwifery alone rather than all medicine, but after the legal proceedings only women may practice the art, which gives her greater autonomy than was granted by the earlier version. While the accusing body in Medina’s rendition is not named, the power in the senate’s decision does come straight from a governing body. There is no doubt that the right to regulate healthcare providers comes from the government. The only active, temporally determined verb in his telling is “resolvió” (it resolved): that is the true action of the story -the senate’s decision. In this just, powerful, male governing body, there is a corollary to Medina’s support of the Protomedicato. This intrinsic support of regulation and the Protomedicato’s aims is all the more clear in that his recounting of the story of Agnodice is followed by another classical anecdote suggesting that the Roman senate also licensed and regulated providers: “habían de poseer reglas y estudio, mediante el qual mereciesen la aprobación” (v). It is by study and licensure (by the regulatory mechanism of a bureaucracy) that the female practitioner should be licit. Medina breaks here from Feijoo’s encouragement of passion and aptitude, suggested in his iteration of the myth by self-study and lack of regulation, and focuses instead on the importance of a governmental regulatory body for a functional medical system. By the time that Navas published Elementos del arte de Partear, and therefore his version of the story of Agnodice, the societal framework around obstetrics and midwifery had developed substantially. In 1794, when the obstetrical course that was part of the surgical curriculum at San Carlos was increased in length to a full year, the university enacted free classes to train midwives in anatomy and best practices, because the numbers of surgeons coming out of the program “would have little effect on the tremendous loss of life associated with childbirth” (Burke 98). It is apparent, in the creation of this class at the end of the eighteenth century, that male practitioners had not thrust women out of the birthing room, and that they were still integral to societal wellbeing. What is more, this cognizance was not only held by the governing heads of the educational bureaucracy that composed both the college and the Protomedicato, but extended to governmental ministries and influenced policy. The first eight midwives to go through this training were hired by the municipal government to oversee sections of the city, and to train other midwives within that purview to increase the standards of care (98). These courses, while not the same training as was received by surgeons, were better than any available previously, and were aimed at retaining providers, and raising the availability of care in an underserved population. Furthermore, while surgical colleges were never able to complete enlightened reforms due to governmental financial restraint, not only were these classes for midwives free, midwives’ licensure was substantially less expensive than that of 96 Johnson, "Eighteenth-Century Obstetrics Manuals" surgeons (Burke 158, 192).18 The creation of these classes, in conjunction with the obstetrical surgical training that the school provided, was designed to “improve the practice of obstetrics without driving women out of medicine” [emphasis added] (Burke 100). Professional training only raised the social prestige of the midwife, much as it did for the surgeon (Usandizaga 217). Navas’s iteration of the tale of Agnodice, because of his retrospective position in regards to these reforms, balances the other two that we have seen. He villainizes the male populace for forcing women to rely on male doctors, saying that women would call Agnodice in order to: “vengarse de los que pretendían violentar el pudor del bello sexo, y obligarlo por falta de comadres á parir delante de los médicos” (xi). This, without equivocation, promotes the female provider, and through her the more empirically based system of learning that produces her. At the same time, however, he removes Feijoo’s suggestion that Agnodice penetrated the world of men, and sidesteps any suggestion of sex in the court proceedings: “acusaron á Agnodice de que siendo eunuco, según su esterior, corrompía las buenas costumbres de las señoras” (xi).19 While he does allow a female voice some influence in changing the mind of the senate -“El bello sexo mas distinguido de Atenas […] se presentó al Senado manifestándole la temeraria resolución de que primero se dejara morir, que llamar á los hombres para que le asistieran en los partos” (xi)- the power of decision stays with the governing masculine body: “Semejante despecho consternó al Senado, y éste revocó la sentencia dada contra Agnodice, y espidió segundo decreto permitiendo á las mugeres el ejercicio de la Medicina en las enfermedades de su sexo” (xi). This outcome too is softer than either of the others, neither restricting women’s practice to solely obstetrics, nor suggesting that men should be disallowed the office. The diachronic perspective offered by Feijoo’s, Medina’s and Navas’s three presentations of the same myth offer an entry into the political discourse of the authors and their times. Medina’s construction of the myth forms a declaration of support for the Protomedicato and its request for the Cartilla nueva y útil, through its focus on the male agency of the outcome, and the limitations placed on the sphere of influence of the female practitioner. These elements support the idea of a regulatory body’s At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the examination fee for surgeons was 2,500 reales, that for bleeders 2,000, and that for midwives 800 (Burke 158-9). For comparison, a loaf of bread cost about 1.25 reales, and a pound of mutton about 2.25 (Hernández Franco 95-96). 18 19 The sexually incapable male, alluded to in the description of Agnodice as a eunuch, was a subject of much debate in the period, due to both the castrato opera singer Farinelli and growing unease regarding the creation of castrati, though the operation was deemed safe, even curative, by the same Hippocratic teachings that were under fire in the birthing chamber (Rosselli 145). DIECIOCHO 39.1 (Spring 2016) 97 decision to register midwives as a strong move, offering a classical foundation for such an idea to non-midwife readers of the text, in order to increase the possibility of popular approbation for the program of education and regulation that initiated his writing. Feijoo, in contrast, wrote before such a plan had been set in action, which led to his use of social anxieties to incite action. From his retrospective position, at a point in history where medical faculties had reconnected with the importance of empirical observation, and the midwife and surgeon both had opportunities for training, Navas draws the middle line between the two: still building a firm approbation of a medical bureaucracy, but without completely excising female agency. Through this comparative reading, the political landscape of the field of obstetrics can be seen to unfold, based around the authors’ support for empirical education. The gendered dynamics of power that appear in the myth of Agnodice are something that continue throughout these works. The supposition of a female voice of authority or position of superiority relates directly to the clash of epistemologies, as it takes power out of the hands of the doctrinally trained, and lays it at the feet of an empirical tradition. In Feijoo’s second example of women’s capacity to practice, the unnamed daughter of German surgeon Mr. Sabary is witnessed by a Parisian surgeon in successful performance of a Cesarean section, an operation that Feijoo calls “la más ardua que hay en toda la extensión de la Cirugía” (239). While the foreignness of this successful, contemporary female practitioner protects Feijoo from too direct of criticism, his reference to Paris is clearly positive, given his Bourbon patronage. In concrete support of the female provider, Medina repeats time and again that she should have predominance in the field (vii, x, 2), and promotes the idea that surgeons should only be called in cases that truly go beyond a non-interventive practice: “los Cirujanos que llaman vulgarmente Comadrones, los debe reservar la honestidad y decencia para los casos únicamente en que ocurre dificultad insuperable por la Matrona; la qual dificultad no es tan freqüente como la vana timidéz del vulgo aprehende” (2). In this statement, Medina accomplishes three things: he recognizes the capacity of women to manage births that have a possibility of success without the intervention of new technologies; he linguistically denigrates his public just as Feijoo does; and he creates a level of equality between uneducated women and educated men. The male midwife, though referred to here with the pejorative nomenclature of vulgarmente, was an educated practitioner, but Medina deems him less worthy than the female midwife, though at the time of his writing, she was relatively uninstructed in the scientific particulars of the trade. The interplay of praise and critique that allows the reader to access so much in Medina’s writing is consistent in Navas’s work as well. His harshest criticism and most politicized statements are often wrapped in seeming 98 Johnson, "Eighteenth-Century Obstetrics Manuals" praise: Gervasio de la Touche en 1687 mandó imprimir una obra con el título de Muy alta y soberana ciencia del arte é industria natural de parir, contra la perversa impericia de las mugeres que llaman comadres, cuya ignorancia hace perecer todos los días infinitos niños y sus madres, &c. El autor se inclina á que conviene que los hombres egerzan el arte de partear, y quiere que las mugeres mas bien paran solas, que asistidas de las comadres, porque todas las parturientes no carecen de los conocimientos precisos para gobernarse en sus partos, en lo cual coincide con lo que hemos dicho de las Hebreas. (lxxviii) This description of a work whose title alone is a vindictive assault on the female midwife seems to give it fair representation, by following the common pattern of introduction, description, and classical referent -a pattern that we see in Feijoo’s letter. Yet Navas’s discussion of the ancient Jews, sixty pages prior to this reference, makes the comparison far from complimentary. Though the women to whom he refers to did not use midwives, they did not face the dangerous and difficult process of birth alone by choice, but because the Pharaoh had ordered that, on pain of death, midwives kill all male offspring, whether they would or no (Navas viii). This allusion doubles the negative connotations of the historical, Biblical example as it both plays on Spain’s well-established anti-Semitism,20 and suggests that Gervasio’s theory is tantamount to filicide. Navas uses the paradox in his description, between the men who should be in control because women are dangerous and the women who understand how to govern a labor, to promote the idea that women know their business. What is more, his criticism creates a linguistic tie between the author’s message and his readership, by the use of a first person plural in reference to the previous episode in his text, making his readership an inherent part of the critical process. Navas’s history of obstetrics also offers very direct support for the female provider’s place in the field. In discussing a 1760 book by a London midwife, which purports to be a treatise against abuses of birthing technologies, but which “debe titularse tratado contra los comadrones” (lxv), he poses the question directly: “¿pero quién negará que las comadres pueden adquirir y poseer los mismos conocimientos que los comadrones? Y concedida esta igualdad, ¿por qué han de merecer los hombres la preferencia?” (lxv). Navas does, however, use gendered language in a way that plays into the empirical element of the midwife’s identity as female lay practitioner, revolving around the rhetorical expression “dar a luz” (to give This century’s struggle between a great need for doctors and a social repugnance toward Jewish healthcare providers is visible in that one of the requisites for the midwife’s licensure was proof of limpieza de sangre, going back two generations (Usandizaga 217). 20 DIECIOCHO 39.1 (Spring 2016) 99 birth), which he first uses to describe the publication of a book when he references a text by female author and midwife Luisa Bourgeois: “Después dio á luz la apología contra las declaraciones de los médicos, obra que ha tenido varios traductores” (lxxi). While Navas’s very inclusion of works by female authors and written in direct apposition to male-authored texts suggests a parity in understanding, the description that he gives of Bourgeois’s text suggests its social recognition as well, in his explicit reference to the book’s several translations. The use of the expression that she “birthed” her work is yet more striking in the broader context of Navas’s history, as the majority of the literary products that he discusses are not granted such evocative terminology, being most commonly referred to as “published” (repeated some ninety times in the text).21 However, this expression is not solely applied to the work of female writers: “Don Josef Bentura, cirujano comadron de Madrid, dió á luz en 1788 una obra que hace muchos años tenía compuesta” (civ). Navas then showers praise on this birthed book: “El deseo de emplear la doctrina de esta obra […] me estimuló á leerla con atencion luego que se publicó, y á la verdad me admiró el buen exito de algunas de las observaciones que espone en prueba de su doctrina” (civ). Such an introduction, combining biological (female) creation with a high level of scholarship, lauds it as a product of personal experience, rather than something created from sterile theory. Indeed, in one of his numerous first person asides, Navas reiterates this connection between creation and experience. “[E]l genio y al contínuo egercicio que el Señor Bentura ha tenido en partear, le hacen superar con medios inferiores á los del dia, lo que á otro le sería imposible” (civ). It is Bentura’s constant practice and attentiveness to his craft that Navas cites as the basis of his success, and for which he uses a metaphor for creation that breaks the continuity of a doctrinal educational narrative, by its semantic reference to biological reproduction. It is through this valorization of practice over theoretical preparation that Medina and Navas place their texts on the empirical side of the eighteenth century’s clashing scientific epistemologies. Because Cartilla nueva y útil was written to provide the most practical parts of a theoretical education to practitioners of an empirical tradition, it deals from its foundation with the conflict between rational and traditional facets of the educational world. Interaction with both sides is clear throughout the book in Medina’s double intended audience: the midwives to whom it is addressed, and the elite of the medical educational system. This doubling is clearly visible in his incessant use of the third person in referring to women, which, in combination with the commentary that he gives justifying their practice, creates them as object as much as addressee. He describes the format of the book, (visible in Figure 2), as: “toda en metodo de preguntas, 21 For background on the childbirth metaphor of literary production in interaction with the phallic energy of the pen as the instrument of creation, see Friedman. 100 Johnson, "Eighteenth-Century Obstetrics Manuals" y respuestas, y con la posible brevedad, y claridad; por que dirigiendose para Mugeres, que apenas saben leer, y escribir, y que hasta aora, por no haverse sujetado á studio alguno, se les ha de hacer muy ardua qualquier literaria enseñanza”(ix). If this text were directed towards women, as he claims both here and in its title, this explanation would not be couched in negative, third person descriptions of that target audience. Furthermore, this depiction suggests that his secondary audience is opposed to an educational system based on imparting practical information rather than theory. The question and answer catechistical structure of the book is in itself a strategy that engages with the difference between dogmatic and scientific methods of educational practice. Figure 2. Don Antonio de Medina, Cartilla nueva útil y necesaria para instruirse las Matronas, que vulgarmente se llaman Comadres, en el oficio de Partear (Madrid: Oficina de Antonio Sanz, 1750) In her article “Reading in Questions and Answers: The Catechism as an Educational genre in Early Independent Spanish America,” Eugenia Roldán Vera describes the split historical trajectory of the catechism as an educational tool: a split that centered on the secularization and growing accessibility of education. The formation of Medina’s question and answer structure falls in line with seventeenth century scientific catechisms, which strove to arrive at convincing truths behind unpopular positions through DIECIOCHO 39.1 (Spring 2016) 101 the presentation of opposing viewpoints, rather than with more traditional religious instructional texts that used the format to prompt previously memorized responses. Medina’s strategy allowed his text not only to provide information that the midwife should memorize, but also to debunk unfounded traditions in both lay practices and established doctrine, while distancing the author from overly controversial opinions (24). Just as Feijoo’s letter suggests that training women would not require the populace to rethink its opinion of them as weak, Medina couches his desire to engage in dialogic philosophical discussion in the assumed stupidity and laziness of his supposed female primary audience.22 However, as for Feijoo, this stupidity is clearly superficial for Medina, as can be seen in his proposed outcome to better education: “[S]e espera recobren nuestras Matronas Españolas aquel famoso crédito que tuvieron en el antigüo, que tengan en ellas, las que paren, la conveniente confianza, y goze el Publico de el Consuelo, y satisfaccion de no exponer sus mugeres al arbitrio de gentes sin pericia, ni practica” (x). This appeal to a golden past ties into the ilustrados’ discontent with their retrospective, recursively valorizing public, yet it does so in a way that suggests educated, well practiced women as a means of accessing that former glory. Further, the “gentes sin practica” that he mentions here, under whose care Spanish women should not have to suffer, include university students who, at the time of his writing, could still receive a medical degree without ever having touched even a cadaver, let alone a living patient. This openness to categorizing physicians as bad practitioners is supported by Medina’s distribution of importance in theoretical areas of the art, which he weights heavily toward anatomy and practical experience, suggesting that no book can provide a complete education: “La verdadera idea y conocimiento de estos huesos, de su figura, tamaño y articulación, no la pueden conseguir las Matronas por la sola explicacion y noticia que se les dé en los libros, y así es necesario que á presencia de Esqueleto, y de un Maëstro Anatómico lo pretendan” (10). This assertion clearly frames educational priorities that revolve around observationally derived knowledge, as well as demanding training for midwives beyond his book, critiquing university faculties that lack in praxis, and reinforcing the existence of an expected readership in the academic elite. As I have mentioned, Medina’s criticism of untrained practice often 22 The questions that Medina poses are simple and straightforward. E.g.: “¿Qué se debe entender por Arte de Partear?” (1), “¿En qué se debe fundar la mejor enseñanza del Arte de partear?” (8). His answers, on the other hand, while worded plainly, are clearly the voice of authority both by their length, and in that the answers themselves create discourses with other, often unfounded or false, trains of thought. If the answerer were only giving back information that was already conveyed, as is the case in religious catechisms, this type of discussion would not happen. 102 Johnson, "Eighteenth-Century Obstetrics Manuals" correlates with his description of things done vulgarmente, a term that carries the double signifiers of “crudely” and “popularly,” which again suggests his agreement with Feijoo’s opinion of their public. While the appellation of both female and male midwives with the term “comadron/a” is described in this way, he also uses it extensively to debunk folkloric interpretations of anatomical and biological functions that empirical study would nullify: “P: Por qué estando el feto encerrado, y nadando en esta agua los nueve meses, no se ahoga? R: Por que dentro del útero, ni respire, ni tiene necesidad de respirar; y por consiguiente, ni excrementa, ni llora, como vulgarmente han creído” (23). This imagined crying, breathing fetus is a relatively extreme example of his critiques valorizing observation over tradition, which extend beyond myths based in folk wisdom to Hippocratic teachings. While these teachings can be easily refutable by observation, they were canonical both medically and legally in the period. “P. Puede haber preñez de trece ó catorce meses, y aún de uno y dos años? R. Aunque las Leyes en favor del próximo lo toleran, es vulgar credulidad el confesarlo” (37). Here, the law and medical canon are demonstrated as irrational and reliant on dogma, rather than empirical evidence. This difference between tradition and observable truth, taken to the point that it questions established law, is crucial. Practical experience and unbiased observation offer the truth in a way that tradition cannot, regardless of its source material. The negative connotation of commonality and of the term “vulgarmente” is, however, something that can be warded off by experience. For example, after the birth of an infant and the cutting of the umbilical cord, “se le embolverá en los paños y pañales, que vulgarmente se sabe” (66). This information is valuable enough to include due to of the practical experience involved, even though it is so commonly know that it triggers his usually critical adverb. This emphasis on experience and observation is the foundation of much of his praise as well. “Muchos tienen por natural, y facil tambien al parto en que la criatura presenta lo primero ambos pies, y por ellos es extrahido sin dificultad, como cada día muestra la experiencia” (44). Medina’s argument for empirical education is rooted in this differentiation between observation and blind belief. In Elementos del arte de Partear, Navas too focuses on experience as the wellspring of knowledge. To emphasize something said or written, he references the author’s experience rather than his/her education or pedigree, often repeating the descriptive phrase “despues de muchos años de práctica” (lxxxi, lxxxiii, et al.). He also distinguishes between erudition and practical experience, with more value laid on the latter: “En fin, La Motte es, como lo pinta Haller, no erudito, pero muy práctico, de buen juicio, que observó mucho, que con sencillez vio mejor que sus predecesores” (lxxxi). Navas’s positive focus on interior traits, like judgment and skilled observation, and on practical experience, suggests that these traits supersede a lack of erudition. In discussion of educational texts DIECIOCHO 39.1 (Spring 2016) 103 it is also easy to see Navas’s focus on utility over extensive rhetoric and theoretical reference, especially when it is coupled with much field experience: Mr. Barbaut, comadron de las escuelas de San Cosme, después de muchos annos de práctica publicó en 1775 un Curso de partos para los estudiantes y para las comadres. El autor llenó la idea que se formó de dar á sus discípulos un compendio de los preceptos que les enseñaba, con claridad, y sin superfluidades. Al paso refiere el suceso de varios casos para aprobar su doctrina. (lxxxiv) This text, lauded for its simplicity, focus on basics, and its grounding in the author’s experience –cited twice in this excerpt– is exemplary of the ilustrado advancement of function over form. Yet in the supposed simplicity of these enlightened medical texts, it is possible to access the mix of sweetness and utility that is characteristic of the movement, and that has value beyond their physical descriptions of bone and knife. Antonio Medina’s Cartilla nueva util y necessaria para instruise las matronas que vulgarmente se llaman Comadres en el oficio de Partear, Juan de Navas’s Elementos del arte de Partear, and Benito Jerónimo Feijoo’s “Uso más honesto de la arte Obstetricia” offer insight into the epistemological confrontation that so influenced the reformative power of Spain’s ilustrados through their textual constructions of the midwife. By her position as adjacent and necessary to, yet separate from the male medical hierarchy, the eighteenth century midwife becomes the crucible for a shift in worldviews. The role that this textual midwife plays, in spite and because of the abuse that she receives, suggests that she, along with her socio-medical milieu, is a figure crying out for further investigation. WORKS CITED Achterberg, Jeanne. Woman as Healer. Boston: Shambhala, 1990. Burke, Michael E. The Royal College of San Carlos: Surgery and Spanish Medical Reform in the Late Eighteenth Century. Durham: Duke UP, 1977. Calderón de la Barca. La vida es sueño. Ed. Evangelina Rodríguez Cuadros. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1997. Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. Web. 10 Oct. 2013. Cunningham, Gary F., Kenneth J. Leveno, Steven L. Bloom, et al. Williams Obstetrics, 24th ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 2014. Deacon, Philip. “Spain and the Enlightenment.” The Cambridge History of Spanish Literature. Ed. David Gies. New York: Cambridge UP, 2004. 104 Johnson, "Eighteenth-Century Obstetrics Manuals" Donnison, Jean. Midwives and Medical Men. New York: Schocken Books, 1977. Feijoo, Benito Jerónimo. “La voz del pueblo.” Teatro critico universal. Vol 1. Madrid: D. Joaquín Ibarra, 1778. 1-19. Proyecto Filosofía en español. Web. 4 Apr. 2015. ___. “Uso más honesto de la arte Obstetricia.” Cartas eruditas y curiosas. Vol. 2. Madrid: Imprenta del Supremo Consejo de la Inquisición, 1758. 235240. Fernández, Enrique. “Tres testimonies del control y desplazamiento de las comadronas en españa (siglos XIII al XVII).” Revista Canadiense de Estudios Hispánicos 32.1 (2007): 89-104. Web. 4 Apr. 2015. Friedman, Susan Stanford. “Creativity and the Childbirth Metaphor: Gender Difference in Literary Discourse.” Feminist Studies 13.1 (1987): 49-82. Web. 1 Apr. 2015. Gélis, Jacques. History of Childbirth. Boston: Northeastern UP, 1991. Granjel, Luis. La medicina española del siglo XVIII. Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, 1979. Hernández Franco, Juan. “El precio del trigo y la carne en Lorca: su relación con el Mercado nacional durante la segunda mitad del siglo XVIII.” Revista Murgetana 61 (1981): 81-97. Web. 28 April, 2015. Howe, Elizabeth. The First English Actresses: Women and Drama 1660-1700. New York: Cambridge UP, 1992. Ilie, Paul. The Age of Minerva: Cognitive Discontinuities in Eighteenth-Century Thought. Vol 2. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 1995. King, Helen. “Agnodice.” The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Eds. Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth. 3rd ed. Oxford UP, 2005. Web. 4 Apr. 2015. ___. Midwifery, Obstetrics and the Rise of Gynaecology. Burlington: Ashgate, 2007. Marland, Hilary. The Art of Midwifery. New York: Routledge, 1993. McClelland, I.L. Benito Jeronimo Feijóo. New York: Twayne, 1969. DIECIOCHO 39.1 (Spring 2016) 105 McKendrick, Melveena. “The ‘mujer esquiva’: A Measure of the Feminist Sympathies of Seventeenth-Century Spanish Dramatists.” Hispanic Review 40.2 (1972): 162-197. Web. 4 Apr. 2015. Medina, D. Antonio. Cartilla nueva útil y necesaria para instruirse las Matronas, que vulgarmente se llaman Comadres, en el oficio de Partear. Madrid: Oficina de Antonio Sanz, 1750. Hathi Trust. Web. 4 Apr. 2015. Medina Domínguez, Alberto. Espejo de sombras: sujeto y multitud en la España del siglo XVIII. Madrid: Marcial Pons, 2009. Navas, D. José de. Elementos del arte de Partear. Madrid: Imprenta de Sancha, 1815. Hathi Trust. Web. 4 Apr. 2015. Orozco Acuaviva, Antonio. “Médicos italianos en la España ilustrada.” Historia y Medicina en España. Ed. Juan Riera Palmero. Madrid: Junta de Castilla y León Consejería de Cultura y Turismo, 1994. 189-199. Ortiz, Teresa. “From Hegemony to Subordination: Midwives in Early Modern Spain.” The Art of Midwifery: Early Modern Midwives in Europe. Ed. Marland, Hilary. New York: Routledge, 1993. 95-114. Pardo Bazán, Emilia. “El Comadrón.” Cuentos completos. Ed. Juan Paredes Nuñez. Vol. 2. La Coruña: Fundación Pedro Barrie de la Maza, Conde de Fenosa, 1990. Pardo Tomás, José and Àlvar Martínez Vidal. “The Ignorance of Midwives: The Role of Clergymen in Spanish Enlightenment Debates on Birth Care.” Medicine and Religion in Enlightenment Europe. Eds. Ole Peter Grell and Andrew Cunningham. Burlington: Ashgate, 2007. 49-62. Rivas, Duque de. Don Álvaro o la fuerza del sino. Ed. Alberto Sánchez. Madrid: Cátedra, 2004. Roldán Vera, Eugenia. “Reading in Questions and Answers: The Catechism as an Educational Genre in Early Independent Spanish America.” Book History 4 (2001): 17-48. Web. 4 Apr. 2015. Rosselli, John. “The Castrati as a Professional Group and a Social Phenomenon, 1550-1850.” Acta Musicologica 60.2 (1988): 143-179. Web. 4 Apr. 2015. 106 Johnson, "Eighteenth-Century Obstetrics Manuals" Sheridan, Bridgette. “Whither Childbearing: Gender, Status, and the Professionalization of Medicine in Early Modern France.” Gender and Scientific Discourse in Early Modern Culture. Ed. Kathleen Long. Burlington: Ashgate, 2010. Usandizaga, M. Historia de la Obstetricia y de la Ginecología en España. Madrid: Labor, 1944. Wayman, Erin. “Timing of Childbirth Evolved to Match Women’s Energy Limits.” Smithsonian. Smithsonian Mag., 29 Aug. 2012. Web. 15 May 2015.