Document 14157987

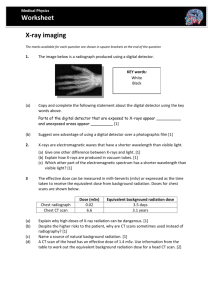

advertisement