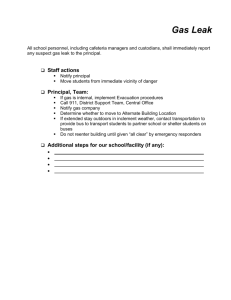

SAFETY AND SECURITY CONCERNS: PERCEPTIONS OF PREPAREDNESS OF A

advertisement