360 Degrees of Blackness: African- winter 2002

advertisement

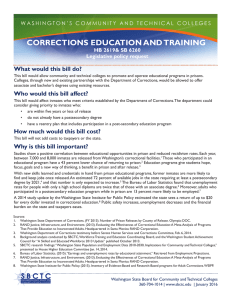

winter 2002 PRISON ISSUE 360 Degrees of Blackness: African-American History in a Prison Education Program Jill Paquette............................................1 Education Reintegration at Hampden County William R.Toller and Daniel E. O’Malley...............................................3 Opening Doors: An ESOL Workbook by Prisoners, for Prisoners Kristin Sherman..................................... .6 Poems from Prison Anne Flaherty.........................................7 A Tutor and Learner at the ACI Janet Isserlis and Jessica Gonzalez............. 8 Reflections from Inside Arnie King...........................................10 Behind Bars: An Experiment in CrossCultural Training Kristin Sherman.....................................11 The Voice in The PEN Rodney Wilson.....................................12 State of the State— Behind Bars: ABE for the Incarcerated Bob Bickerton and Jane Brown................ 16 NELRC Notes: Education for Community Participation Andy Nash..........................................18 Department of Correction in Massachusetts— An Overview Larry Pollard.........................................19 The Right Thing Maurice Penn.......................................20 Resources on Prisons..............................21 360 Degrees of Blackness: AfricanAmerican History in a Prison Education Program By Jill Paquette A s a first-year teacher in the non-traditional environment of a prison, I’ve found that my best lessons have been thematically based. I’ve developed interdisciplinary units around the novel Of Mice and Men, the play A Raisin in the Sun, career/employment issues, twentieth century America, and other topic areas. But no lesson that I have prepared can top a thematic unit on AfricanAmerican history, one that was developed at the suggestion of a student, curious about his heritage. I developed this unit while teaching at the Suffolk County House of Corrections in Boston. My students were men, mostly in their 20s and 30s; who read between a 5th and 6th grade level. “Africa Then, African Now—360 Degrees of Blackness,” as the project came to be known, had very modest beginnings. My initial aims were to introduce and familiarize students with a few components of African-American history, including ancient African civilizations, the Massachusetts 54th Infantry, and the Harlem Renaissance. Educational objectives prior to beginning the unit included: highlighting less familiar people and aspects of black history, improving literacy, enhancing computer literacy, practicing group presentation skills, and improving writing fluency. Continued on page 5 System for Adult Basic Education Support Funded by the Massachusetts Department of Education Field Notes Foreword This issue of Field Notes offers insights and information about adult basic education in one of the most challenging settings— correctional facilities. The bias is pretty clear: education for inmates is a powerful tool for transformation; prisoner education should not be viewed as an add-on, a luxury, or a form of coddling. The perspectives of prisoners in this issue are highlighted through articles, poems, short reflections, and drawings. We have also showcased the work of teachers who have found creative, respectful ways to approach adult basic education in correctional facilities despite the institutional limitations of the work. Resource listings—Web Sites, curricula, guides, articles, and videos— are included for a variety of purposes: to assist inmates in the re-entry process, to inspire and inform teachers, and to enlarge our understanding of prison culture. This issue comes at a time when education for prisoners is more marginalized than ever. Although Adult and Community Learning Services (ACLS ) at the Department of Education still funds some programs for inmates, recent massive cuts from the Massachusetts Department of Correction (DOC) budget has eliminated adult basic education programs entirely from many facilities. I recently visited a medium security facility to meet with a long-term inmate and to discuss prison education and other issues. Just getting through to the visiting room was a lesson in itself. My reactions to the terse, disrespectful manner of the guards as they frisked me, refused to answer questions, and reprimanded me (for having a tear in my jacket pocket) pointed to my naivete about prison culture. In putting this issue together I was reminded that most of us in adult basic education know very little about corrections as an important “service delivery” area for ABE. I hope that this issue of Field Notes offers a place to get started in filling in the gaps in our knowledge and understanding. Lenore Balliro, Editor 2 Field Notes Mission Statement and Editorial Policy Mission Field Notes is an adult basic education (ABE) quarterly, theme-based newsletter. It is designed to share innovative and reliable practices, resources, and information relating to ABE. We attempt to publish a range of voices about important educational issues, and we are especially interested in publishing new writers, writers of color, and writers who represent the full range of diversity of learners and practitioners in the field. Field Notes is also a place to provide support and encouragement to new and experienced practitioners (ABE, ESOL, GED, ADP, Family Literacy, Correction, Workplace Education, and others) in the process of writing about their ideas and practice. Editorial support is always provided to any writer who requests it. Teachers, administrators, counselors, volunteers, and support staff are welcome to write for Field Notes. Our Funder Field Notes is published by the System for Adult Basic Educational Support (SABES) and funded by Adult and Community Learning Services (ACLS), Massachusetts Department of Education. The Central Resource Center (CRC) of SABES is located at 44 Farnsworth Street, Boston, MA 02210. Our Editorial Policy Unsolicited manuscripts to Field Notes are welcome. If you have an idea for an article or wish to submit a letter to the editor, contact Lenore Balliro, editor, by phone at 617-482-9485, by email at <lballiro2000@yahoo.com>, or by mail at 44 Farnsworth Street, Boston, MA 02210. Submission deadlines for upcoming issues are published in each issue of Field Notes. Opinions expressed in Field Notes are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editor, SABES, or its funders. We do reserve the right to decline publication. We will not publish material that is sexist, homophobic, or otherwise discriminatory. Our Reprint Policy Articles published in Field Notes may be reprinted in any publication as long as they are credited to the author and Field Notes. Field Notes Advisory Board Susan Arase, Susan Hershey, Tom Lynch, Michele Sedor, Sarah Wagner, Lynne Weintraub Editor: Layout: Proofreading: Lenore Balliro Heather Brack Deb Liehs Lou Wollrab winter 2002 Field Notes Education Reintegration at Hampden County By William R. Toller and Daniel E. O’Malley A t the Hampden County Sheriff’s Department, in Ludlow, Massachusetts, we have been focused on preparing our inmate population to become responsible citizens since 1975. With over 80 percent of our inmate population high school dropouts and lacking vocational skills, the need for correctional education was readily apparent when we moved from the old York Street Jail, built in 1886, to Ludlow, in 1992. Correctional programs had significantly helped us in managing our record overcrowding numbers, which hit 726 inmates in 1985 in space designed for 256 inmates. From 1976 to 1992, over 1,759 inmates had achieved their high school equivalency diploma; 2,000 inmates had been placed in unsubsidized employment as a result of vocational training; and over 1,000 inmates had received substance abuse treatment at our correctional alcohol program in Springfield. As we began our education efforts at our new facility in Ludlow in 1992, our ABE program grew quickly from an average daily attendance of 75 students at York Street to over 250 students by 1993. As our education staff utilized the SABES staff and program development process each year, we identified a pressing need for our correctional education efforts: a reintegration counselor to assist students in the next step, completing their educational goals in communitybased programs. With the assistance of a VISTA volunteer, we contacted the Center for Crime, winter 2002 Communities, and Cultures in 1997 and secured a $150,000 grant to fund an education reintegration model for two and a half years. The Education Reintegration Model Dan O’Malley was hired as our education reintegration counselor under the Crime, Communities, and Culture grant in February 1998. The purpose of the grant was to transition inmates from educational courses of study at the facility to community-based adult education programs, including college level programs of instruction. The original grant also required the educa tion reintegration counselor to provide vocational and career guidance to inmates. The position has required the following: ◆ an extensive knowledge of academic, career, and occupational professions available to high school graduates, GED recipients, and college level students; ◆ extensive knowledge base of the community-based adult programs available to released inmates; ◆ the ability to develop and implement programs of study that allow for the realistic attainment of each participant’s educational goals and career objectives; ◆ the demonstrated ability to provide educational and occupational guidance consistent with each participant’s academic abilities and career objectives; ◆ an extensive knowledge of all aspects of federal student aid (FAFSA). The follow-up aspect of the program provides participants with counseling to continue with their chosen course of study and also provides educational advocacy for each client. The average student in our program is a young Hispanic male from Springfield, around 22 years old, with a record of sub stance abuse and prior arrests. Follow-up is key to achieving success once released. At the onset of the program, Dan met with over 25 communitybased adult education programs to explain the education reintegration program to the providers, make introductions, and assess the compatibility of the community-based programs with our facility’s education program At a series of internal meetings, Dan also explained the education reintegration program to the teaching staff and sought support for effective teacher input into the reintegration process. Support from Teachers The teaching staff was overwhelmingly supportive of the reintegration concept and began to make immediate referrals for those inmates who were about to be released from the facility. Dan also began a series of meetings with currently incarcerated inmates to explain the education reintegration model. Continued on page 4 3 Field Notes Education Reintegration... Continued from page 3 Outcomes Prior to the incorporation of the education reintegration model at the Hampden Sheriff’s Department, only 30 percent of inmates indicated a desire to continue with formalized education upon release. Now, after five years of education reintegration services, almost 75 percent of inmates express a direct interest in furthering their educa tion upon release from custody. Ceremonies On a monthly basis, the Hampden Sheriff’s Department holds a “Student of the Month” cer emony to recognize a student who has demonstrated academic and social improvement. At each ceremony, Dan speaks to the students and explains the educational opportunities that are available upon release. Students are encour aged to continue with their studies when released and are advised to call Dan to arrange for educational placement in the community. Dan has also arranged for communitybased adult education providers to come into the facility and explain their education programs to the inmates at the “Student of the Month” ceremony. Local community colleges and local ABE providers have now participated in our “Student of the Month” ceremony. Snapshot The operation of the education reintegration program can be best illustrated by an actual example: Darnell H. received a lengthy sentence to the Hampden County House of Correction. While incarcerated, Darnell obtained his GED and then began a post-secondary studies at the facility offered by a 4 local community college. After accumulating a number of college credits and having served his complete sentence, Darnell was released. Prior to his release, Darnell met with Dan where he received a number of services to help ensure his acceptance into a community college and the successful continuation of his education. For example, Darnell’s financial aid (FAFSA) was processed over the Internet; his transfer credits were incorporated into his college transcripts; he received an appointment for long-term academic/placement counseling at the college. He is scheduled to start his college work in fall 2002 and is expected to graduate in 2003. The actual mechanics of the education reintegration program are closely linked with the overall Hampden County Sheriff’s “After Incarceration Support Services” Department (AISS). Prior to release, every inmate at the Hampden County Sheriff’s Department develops a detailed release plan that addresses issues such as housing, mental health, substance abuse, and education. At the release planning groups, every inmate who expresses an interest in continuing with education meets individually with the education reintegration counselor and a followup plan is developed. Mentors and Follow-up Once a released inmate calls for an outside education appoint ment, the education reintegration counselor schedules the appointment, usually right at the adult education program, and the inmate enrolls in school. A mentor, an employee of the Hampden Sheriff’s Department and former inmate, periodically checks with the released inmate to see how things are going. The mentor provides a key role in the success of the released inmate (now a student) by acting as a transitional figure between the student and the reintegration counselor. If the student stops attending school or needs additional support, the mentor can help follow through to make sure adequate support is provided. What the Research Shows Education programs do dramatically reduce recidivism as a recent Correctional Education Association staff survey and our research clearly show . Our overall recidivism rate for inmates who have been released for two years or more since 1999 is approximately 22 percent; our recidivism rate for those who have successfully participated in education programs is less than 12 percent. Our challenge as correctional educators is to continually develop the lifelong learning concept with our students and to help them take that next step by enrolling in adult basic education programs in our communities. William R. Toller is assistant superintendent of human services at the Hampden County Correctional Center in Ludlow, where he has been employed since 1976. He can be reached by email at <Bill.Toller@ SDH.State.Ma.Us>. Daniel E. O’Malley is the education reintegration counselor at the Hampden County Correctional Center. He can be reached at <random21@ aol.com>. winter 2002 Field Notes 360 Degrees... Continued from page 1 Little did I know at that time how much more this would actually involve and include. By the time John Coltrane’s saxophone faded out and the director yelled “Cut!,” our ‘‘little’’ proj ect was close to two months in the works. We began with a mini-lesson on Nubian and Egyptian cultures in which students teamed up to tackle a single area of the ancient cultures, for example: family life, religion, contributions to society, and related topics. Each group was required to read and understand its piece, summarize it, then jointly present the newly discovered information to the rest of the class. Lack of preparedness by some of the presenters and difficulty of material caused this part to drag a little. After that section we spent some time looking at the state of Africa today. Geographics, demographics, economics, and other areas were presented with the help of some excellent overhead transparencies, which helped to spark student interest. From there we jumped ahead to the Civil War era and the Massachusetts 54th Infantry’s distinguished role in history. We dove into facts and stats, as well as personal narratives from those who were there. It was around this time that I realized that something special was about to happen. Taking a Back Seat to Students I decided to take a back seat and allow the students to steer our next course. We held a group meeting in which I told the class that I wanted to put together a comprehensive class project presenting all our new information. I would supply all the resources and assistance winter 2002 needed, but they were responsible for collectively deciding what that project would be, and how to get it from conception to completion. We bounced around many ideas before deciding on constructing a largescale timeline that would wrap around the classroom and present articles, pictures, and other information about each piece that we covered. We designated two student project leaders who would coordinate and direct the massive project. We increased the caseload to include the transatlantic slave trade, slavery in America, the Civil Rights movement, and AfricanAmericans today. It was as if our team captain yelled “break,” the huddle dispersed, and each player set off to do his job. Some navigated their way through Encarta Africana, an unbelievably resourceful computerized encyclopedia of Africana. Others dove into textbooks and other printed resources. Still others viewed video libraries during the research portion of the project. poetry and art created solely by African-Americans, and listen to the smooth sounds of Coltrane, Armstrong, and other jazz greats. We even invited guests to sit and further explore any related areas of interest to them. This followed a 15-minute oratory/theatrical walk through history, which verbally highlighted our educational journey, narrated by the “experts” that had researched and prepared that section. This piece was entirely arranged by my students, who caught me by surprise when they handed me my script, detailing the lives of a few outstanding black women. All in all it was a multimedia event that left us with an engaged audience, a wealth of information, swelling pride, unbelievable camaraderie, and a standing ovation. One staff member, our librarian and a Congolese native, was so impressed that he encouraged us to videotape the presentation as a permanent documentation to have and show in our institutional library. Mini-Museum and Celebration Unexpected Outcomes Our timeline was literally bursting at the seams. So much so that it actually more closely resembled a mini-museum. Our small cinder-block classroom was transformed into a home of tribute to African history and to my students‘ vision and perseverance. I arrogantly decided that the museu m wasn’t enough. I wanted to share, celebrate, and show off our work. Nearing the end of our project, I informed the class that we were going to host a party, an open house that would allow other interested students and staff to view the layout of actual sardine-packed slave ships, read documents and journal entries, skim through volumes of What started as a less than adequately developed lesson ended as a source of knowledge, pride, and development for my ABE students. Each and every member contributed: reluctant writers completed essays, less than artistic individuals designed and colored murals, and computer-phobes navigated CDROMs. During this time, my class attendance and size multiplied and students excelled in working both independently and cooperatively. Most importantly, this group gained a valuable sense of pride in themselves. The project exceeded the expectations of even the most optimistic in the group. Continued on page 9 5 Field Notes Opening Doors: An ESOL Workbook By Prisoners, for Prisoners By Kristin Sherman O pening Doors is a workbook geared toward intermediate and advanced learners of ESOL, especially learners representing marginalized populations. What is unique about this book is the collaborative process that produced it. The idea for the workbook arose from the stories that learners in my ESOL classes at the Mecklenburg County Jail (in Charlotte, North Carolina) were writing. Two years ago, Luis Rodriguez, a Chicano poet and the author of Always Running, gave a writing workshop to the ESOL students in the jail. The students responded so well that I asked other writers in the Charlotte community if they would be interested in working with the students on their writing. Irania Patterson of the Public Library of CharlotteMecklenburg County and Dannye Romine Powell, a columnist for the Charlotte Observer, also came out and taught the students about storytelling and poetry. Some of the writing generated from those early workshops appears in this workbook. The Students Many of the students had less than six years of education, and some could barely read in any language. While some students had worked for years in restaurants or in construction, others had no work experience at all. I thought that publishing their writing would encourage them to value literacy more and begin to identify themselves in a new way— as writers. Because of the relatively low level of literacy and English proficiency of some of the students, I wanted to include oral histories and illustrations, and so allow all students to express themselves in a way they felt comfortable and competent. I approached Frances Hawthorne, an artist and art instructor with extensive experience in community art, to offer art classes to the ESOL students. The illustrations on the cover and throughout the book are the result of the nine months of instruction the students received. Gradually, the book grew from a way for the ESOL learners to express themselves to a way that those learners could help other ESOL learners. We decided to use their writings to help teach English by creating an instructional workbook. We wanted the writings to represent a range of genres and difficulty, so we asked 6 already-published writers if they wanted to contribute. Overwhelmingly, the larger writing community responded. The students selected the poems, stories, and memoirs by Julia Alvarez, Sandra Cisneros, Nicholasa Mohr, Pat Mora, Leroy V. Quintana, and Luis Rodriguez that are included in the workbook. Writing and Artwork In addition to the weekly art classes, we added a writing class to generate enough writing to include in a full-length workbook. All the students in the writing class were either second language learners or bilingual, and were also in the art class. Many assignments linked the writing and the artwork. Because we also wanted the students to acquire real skills, we included them in as much of the creation of the book as possible, so in addition to the writing, the illustration, and the selection of outside work, students helped edit, practiced lesson material, and designed layout. One comment: The students were eager to be part of the project and to contribute whatever they could. In this community, the students often rely on each other to get what they need. The line between help and outright cheating is often blurred. Some of the stories in this book were written with varying degrees of help. Some of the illustrations include images “borrowed” from existent art, images that somehow speak to the student. As far as we know, nothing in this book has been copied wholesale. Design of the Units In general, the units allow the learner to replicate the process that our students went through, moving from a common base of knowledge and language presented in context, through structured practice to a freer expression of the learner’s own experience. The units usually move from easier material to more difficult material. More advanced learners may be able to use the entire unit, whereas intermediate learners may need much more help from the instructor. A few copies of Opening Doors are still available, free of charge. Contact Kristin Sherman at <kristin.sherman@cpcc.edu>. winter 2002 Field Notes Poems from Prison By Anne Flaherty Walk a Mile in My Shoes Walk a mile in my shoes Walk a mile in my shoes Before you go and judge me, Before you get to choose If you can label and begrudge me, Just try these suckers on And, walk a mile in my shoes Well, did you ever raise a family by yourself Without alimony, child support or any help? Did you have to hear Maybe he’ll pay up next year? Just put all your wants and needs on a shelf. Well, mister? (chorus) Have you ever seen the wide eyes of your child When he hasn’t seen his Daddy for awhile? And, he wants a brand new bike, Go ahead honey, pick out the one you like. And you want to see that grateful little smile? Well, Missy? (chorus) And, when the wolf comes a-knockin’ at your door and Tells you, “You can’t live here anymore.” Do you pack your bags and shuffle down the street, Or do you bend the rules a little And, get back on your feet? Well, ain’t life sweet? Walk a mile in my shoes Walk a mile in my shoes Come on, it’s not above you, Don’t make me have to shove you. Just try singing the mother’s blues. And walk a mile in my shoes. Walk a mile in my shoes. If you’ve got something to prove, Walk a mile in my shoes. Life Locked Oh well I’m Multiply conflicted Multiply convicted Of criminal felonies Thrown into this prison Wasn’t my decision No sex and no kizzin Oh, how celibacy fell on me. Stripped of all possessions Stripped of all obsessions Stripped of all concessions I’ve clung to all my life Building up my what-abouts Sizing up my where-abouts Of woe, mischief and strife Letting go of old stuff Letting go of cold bluff Hoping that I get enough Of love to see me through Getting what I earned Getting what I should have learned Getting all the twists and turns Getting straight the plans for me and you Oh, cuz I’m life locked Oh, and I’m shell shocked Oh, and I’m defrocked and re-mocked And you might think it strange That this girl, is ready for a change. . . Anne Flaherty is a singer, songwriter, musician, actress, and founder of Social Justice Today. By the time that this issue of Field Notes is published, Anne will be at a pre-release work program. She can be reached at <SJT2003@earthlink.net>. winter 2002 7 Field Notes A Tutor and Learner at the ACI By Janet Isserlis and Jessica González I n the fall of 1999, while examining the impacts of violence and trauma on learning, I started working as a tutor at the Rhode Island Adult Correctional Institution (ACI) with Jessica González, a bright young woman then preparing for the GED test. From Jessica and Susan, (another woman I had tutored), I learned about their learning and, over time, about how violence and non-violence have shaped them as women, and learners. To write this article about teaching and learning in prison, Jess and I worked together at my laptop. Janet: Working in prison is, in many ways, like working with adult learners anywhere–women want to learn, earn a GED, read the Bible, speak and understand English, learn algebra. Interactions between and among learners and teachers look much like those interactions anywhere. Stepping back, though, there are differences. Materials cannot just be brought in–someone in the prison must approve them; I can’t just give Jessica a pen–someone has to OK that, too. We can’t phone each other directly; I can’t send her anything computer generated; if we want a book, it has to be sent from Amazon or another mail order company. What we are able to do is work on writing about topics that are important to Jessica. We are able to work on my laptop; Jessica taught herself and me how to develop PowerPoint presentations; she and Susan have also practiced typing and refined their skills using word processing software. 8 Jess: Tutoring is not only important to me but it is also fun, I see it as a way of learning my way and not having to learn by someone else’s time. The most valuable thing about having a tutor is the time she/he, in this case Janet, takes out to help me with my writing skills and so many other things. study. Sometimes I feel like I’ve brought the laptop for a play date as she explores software; other times, like today, as we write this piece together, we’re both stretched and engaged in the task before us. Jess: One of the things I have learned to work with in the time I’ve spent with Janet is how to use Working in prison is, in many ways, like working with adult learners anywhere – women want to learn, earn a GED, read the Bible, speak and understand English, learn algebra. When we first started, I was thinking, “another tutor that I will probably be booting out in another few weeks.” Janet was different — she didn’t push me, she let me take my time, and she wasn’t a critic about how I did things. And if I messed up, she wasn’t saying, “Oh, try harder,” she just encouraged me to do better next time. She’s not always so serious about things. Janet: I’ve had the luxury of supporting Jess’s learning as best I can. Because I’m only here once a week, I am aware of the other ongoing courses and learning that Jess is engaged in, but I also have the privilege of moving as slowly or quickly as we determine so that Jess has some control over her learning. For a while last spring we worked together on her telecourse on finance; still for the most part we have some leeway in determining each week, what and how we want to PowerPoint, explore it, use the graphics and sounds. I have made personal presentations in order to learn how to use the software. In addition I have completed a Community College of Rhode Island (CCRI) course in personal finance and I’m still working on completing my GED. Also this coming semester I will enroll in another college course, General Sociology, if it is offered here at the ACI. Janet: One of my frustrations in working within the prison system is that inmates are not allowed Internet access. If Jess’s course isn’t offered for example, in any other context, we would look for alternatives—including online courses. This is not an option here. The system does not allow for individualized learning through the Internet. While the reasons for Continued on page 9 winter 2002 Field Notes A Tutor and Learner... Continued from page 8 barring inmates online access have some merit, it’s hard to imagine that alternatives can’t be sought. I would like to believe that as technology advances further, we might find ways to afford access to learning tools on the internet to women and men who otherwise are limited in their access to current learning materials. I am also aware of the resources that are available to learners at the ACI—a computer lab (not online), a library, GED and other learning texts, dedicated and capable educators. Jess: I hope that in some way all of this makes a difference; there are people like myself in the ACI who really want to learn. Just because I am in here and I am considered a criminal or someone who broke the law doesn’t mean I am stupid and I should be limited only to materials that can help me become a better person in society. I am not just saying this to put one picture in your mind; books are good (and my reading is not limited only to behavior-related texts). However, if I had more access to materials, I’m sure when my release date comes I will have a better chance of defending myself in a world as fast as the one you all live in today. Janet Isserlis, project director of Literacy Resources/RI, has worked with adult learners and educators since 1980, in school, communitybased, workplace, and other settings. Jessica González is a 20 year-old Latina, who has been incarcerated since 1996. She has been working on her education and is also interested in computer engineering, art, and design. winter 2002 New England ABE-toCollege Transition Project By Jessica Spohn Research establishes the need for ongoing education for the exoffender. Levels of educational attainment are directly correlated with an ex-offender’s ability to stay out of jail. However, access to and persistence in education, especially post-secondary education, is the last issue to be addressed as the ex-offender plans for and enters the reentry process. The New England ABE-to-College Transition Project is a partnership between the New England Literacy Resource Center (NELRC) at World Education and 23 adult learning centers in six New England states. The project is funded by the Nellie Mae Education Foundation. The goal of the project is to build program capacity and create opportunities for adult literacy program graduates to prepare for, enter, and succeed in post-secondary education so as to help them improve and enrich their own and their families’ lives. Currently, two of the ABE-to-College Transition programs are housed in correctional facilities: Norfolk County House of Correction in Dedham, Massachusetts, and Webster Correctional Facility in Cheshire, Conneticut. The ABE-to-College Transition program at Webster Correctional Facility works with Gateway Community College in New Haven, Conneticut. The ABE-to-College Transition program at Norfolk County House of Corrections works very closely with three community colleges: Massasoit, Massbay, and Quincy. The teachers in the program are also instructors at the colleges. The program is now in it’s second cycle. Students from the first cycle have successfully completed the program, left incarceration, and are enrolled at all of the collaborating colleges. For more information on the ABE-to-College Transition Project, please contact Jessica Spohn, <jspohn@worlded.org> or visit the project Web site at <<www.collegetransition.org>. Continued from page 5 are still fresh and clear in my mind. And if you asked any of them, I bet they’d say the same. Since then, the construction paper backgrounds have faded, most of the students have left the institution, and the museum has long since come down. However, the memories of this amazing experiment in adult education and the possibilities and precedents that were achieved in the process Jill Paquette worked as a reading teacher at the Suffolk County House of Corrections and was an outstanding softball pitcher for Stonehill College in 2001–2002. She has recently left teaching and plans to pursue a master’s degree, specializing in learning disabilities and multiple intelligences. 360 Degrees... 9 Field Notes Reflections from Inside By Arnie King I dropped out of high school at 17, shot and killed an innocent man at 18, and entered Walpole State Prison at 19, barely avoiding the death penalty. I try each and every day to do something that communicates remorse and to make atonement for the life I took. In a few months, I will honor my 50th birthday with several family members in the prison visiting room, driving orange juice and sharing microwave popcorn. Prison life sucks! Work details in prison consist of janitorial tasks, kitchen assignments, maintenance, and industry factories. Most jobs pay one-to-two dollars each day and unemployment is always quite high in the Massachusetts prison system. The actual work is often menial and requires very little skill to perform. Therefore, I have concentrated on academic studies and rehabilitative programming during this incarceration period of thirty-plus years. One of my earliest, though most significant and meaningful, prison jobs was assistant teacher in the ABE program during the mid-seventies. Walpole Prison was very chaotic and violent, with daily assaults and monthly murders. The school area was a relatively safe environment and the ABE director, Mel Springer, hired me to work with older adult prisoners. I was about 24 years old, with a GED and a few college courses, instructing men in areas of the numbering system, as well as learning the alphabet. Some days were consumed with assisting in reading or responding to a letter from a family member, or being able to fill out an institution form requesting medical services. Education is so very important for individuals to adequately function in our society. Without the fundamentals, it’s clear that one is destined to be unsuccessful. The majority of prisoners enter the “big house” without a GED or diploma. In fact, a large percentage have never been to high school. The adult student in prison must face a major issue of low self-esteem. Am I capable of learning? Why should I? Responses to such questions will emerge after the learning process has gained momentum and short-term goals are accomplished. The world expands beyond the 6x9 cell as one increases understanding of the environment outside it. 10 It has become evident to me that authentic rehabilitation will not occur without including education in the formula. I continued to work in prison education at Walpole, Norfolk, and Bridgewater, where I discovered the rewards of helping others. It became apparent that there were fundamental changes in the lives of the prisoner/students, due to the application of basic education principles. Another important lesson for me was to acknowledge the need for academic education in my life. Teaching others required that I pursue advanced courses and be a positive example. In 1983, I received an associate’s degree in business, and Boston University awarded me a bachelor’s in liberal studies (1986) and a master’s degree in liberal arts (1990). Although I have been accepted in postgraduate programs, Union Institute (1992) and U/Mass–Boston (1999), the wall of prison bureaucracy has prevented further advancement. Despite much success, ABE, GED, ESL, and other academic programs are a very low priority in the prison system. It is more typical for one to receive tutorial assistance from another prisoner in an informal way than from within a structured classroom setting. A great percentage of prisoners are eventually released without adequate skills to function in the community as lawabiding citizens. The challenge is to prepare the prisoner for release while incarcerated by providing the tools and the ability to use them. How can it happen? There are over 100 “lifers” in the Massachusetts prison system with Boston University degrees. A suggestion is to provide training workshops to transform graduates into peer educators to promote the ABE, GED, and ESL programs. Then, with a little innovation and opportunity, men convicted of murder will be able to offer a humanitarian gesture to society and to other human beings from the cell block. More importantly, men will be returning to the community less hostile and more inclined to contribute toward the neighborhood. Arnie King can be reached by mail at Bay State Center, Box 73, Norfolk, MA 02056. He may also be reached via email at <throughbarbedwire@yahoo.com> or visit his Web site at <www.bettercommunities.net/throughbarbedwire.htm>. winter 2002 Field Notes Behind Bars: An Experiment in CrossCultural Training By Kristin Sherman B uenos tardes, me llamo Francisco Martinez, y yo soy de Mexico. Good afternoon, my name is Francisco Martinez, and I am from Mexico. Like many of my students in the jail, this student had an alias. All the jail records listed him as Manuel Rodriguez. With these words of introduction, he claimed his true name, and began his part of the presentation. We were giving a workshop on Latino culture to new detention officers who would, within a couple of weeks, begin their jobs supervising these very same Latino inmates. I teach ESOL to an intermediate class at Mecklenburg County Jail in Charlotte, North Carolina. My students are all Hispanic. About two-thirds are facing serious time on federal charges. They represent different countries, levels of education, and degrees of acculturation. The idea for the training on Latino culture for detention officers at the Mecklenburg County Jail was born a couple of years ago. Students in my ESL class had been experiencing conflict with other inmates and with officers, and felt that much of this conflict had arisen because officers knew nothing about Latino culture. The students submitted a petition asking for such training. At the time, I was working on a project in collaboration with Literacy South, in which I was trying to develop lesson ideas that would help ESL students learn to navigate systems. The officer training seemed like an ideal proj- winter 2002 ect to meet both the students’ needs and my own. I suggested the students “put their money where their mouths were”–that they develop a workshop/presentation that could be used to train officers. Preparing for the Training As a class, we read books and downloaded articles from the Internet to learn about differences between Latino and Anglo cultures. We watched the movie Fools Rush In, which was surprisingly useful in its depiction of the contrast between the two cultures. The students ed their material to several different classes of new officers. Over the following year, both officers and inmates “turned over.” I had a whole new cast of characters in my class, and all of the officers in command positions were new. The trainings were discontinued when a new training officer took over. What hadn’t changed was the conflict between Latinos and the other ethnic groups. Another incident propelled a student into approaching me about the lack of training the officers received in dealing with Latino inmates. One pod supervi- One pod supervisor continually called the Latino inmates “Pancho,” while other non-Latino inmates were addressed respectfully by Mister and their last names. developed a description of Latino culture that they felt was authentic. They also translated phrases that were specific to the jail environment into Spanish. Finally, they came up with concrete suggestions. Meanwhile, I began lengthy negotiations to persuade the command structure and training officers to allow the training. I was able to get the training approved, but I had to deliver it. There were too many obstacles, including security issues, to permit the students to give the training themselves. So, I present- sor continually called the Latino inmates “Pancho,” while other, non-Latino inmates were addressed respectfully by Mister and their last names. I told the student that we had such a presentation, developed by students, but it hadn’t been done in a long time. After that class, I approached one of the captains and the new training officer. Both agreed not only that the training could be done, but also that students could do it. Continued on page 15 11 Field Notes The Voice in The Pen By Rodney Wilson F or nearly two decades, inmates at the Hampden County Jail and House of Correction have contributed to lit erary and artistic newsletters published by the education department. Although the publications have evolved and changed names more than once (Behind the Walls became Tutor Talk became The Pen), the purpose has always been to provide an opportunity for inmate-students to see their writing in print, including poems, essays, letters, movie reviews, and articles, with other inmates and staff. In The Pen, students write of their trials, tribulations, hopes, dreams, frustrations, and fears. They write about their parents, their children, their shortcomings, and their struggles with addiction and anger. Students also contribute impressive artwork. Shortly after September 11, a cover drawing (“One Nation Equal”) of an American eagle with one tear streaming down its face as its wings embraced the Twin Towers and Pentagon paid homage to those lost in the attacks. Another powerful cover art was that of a mother sitting beside a river gently bathing her newborn son (“Mother Bathing Son,” September 2000). A regular feature of The Pen is “Trivia Time,” which prompts students to make a dash for reference works in search of answers to somewhat obscure questions (Example: Where, in March 1946, did Winston Churchill deliver his famous “Iron Curtain” speech?*). The Pen also is a vehicle to publicize students who complete their GED at the Hampden Sheriff’s Department (just over 3,200 at last count), and those men and women who earn recognition as students of the month. *As a guest of President Truman at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. Rodney Wilson began his teaching career at a St. Louis high school in 1990. He has served as Title I teacher at the Hampden County Jail and House of Correction since November 1999. Turn to page 14 to read more excerpts from The Pen! 12 winter 2002 Field Notes Coming Home: A Resource Directory for Ex-Offenders Returning to Greater Boston Communities Published by: Prisoners Re-entry Working Group Coming Home is a compilation of over 300 agencies, organizations, churches, and individuals that can provide assistance and information to ex-offenders. The data on each listing includes name, address, telephone/fax numbers, Web site, services provided, office hours, requirements, cost, languages spoken on the site, and public transportation information. The purpose of this directory is to provide ex-offenders from prison returning to the Boston community with useful information in a useable format so they may know where to go for help in overcoming whatever barriers to gainful employment, education, housing, and other services that may be in their way. It should be useful to agencies and individuals assisting ex-offenders as well as ex-offenders themselves, prisoners developing post-release plans, and prison staff assisting them. ORDER FORM Coming Home: A Resource Directory for Ex-Offenders Returning to Greater Boston Communities Name Agency/Organization Mailing Address Telephone Fax Email Web site Donation: Please check appropriate place. $20.00 if Directory is picked up: (See below for pick up information.) $25.00 if you want the Directory mailed: Number of Directories: Amount enclosed: Make checks payable to: Community Change, Inc.—Directory. Send checks to: Prisoner’s Reentry Working Group, c/o Community Change, Inc., 14 Beacon Street, Room 605, Boston, MA, 02108. Donations must be received before Directory is mailed or picked up. To order by phone to arrange to pick up a Directory, contact Carol Streiff by phone at 617-236-1808 or by email at <csstreiff@ix.netcom.com>. winter 2002 13 Field Notes Excerpts from The Pen* Third Time’s a Charm By José Colón Change by Christian Alvarez Behind the Walls By Raymond Cordero (Translated by Oscar Chaverri) Incarceration is the punishment one pays for violating an established law. Incarceration separates individuals from society to keep them from violating more of its laws. Incarceration could be the greatest humiliation for a human being, but it could also be the best reason to change and become somebody useful in society. Incarceration helps a lot of people to change their lives completely from negative to positive attitudes. It also helps many people learn habits necessary to avoid ever returning to prison. Other people, unfortunately, decide not to change and fall back to the vicious cycle that brought them to prison in the first place. We have to realize that we are powerless to resolve our problems as they occur outside the prison. However, we are not powerless to equip ourselves with the tools necessary to effectively and lawfully deal with life once we are enjoying freedom. Incarceration must have such an effect for us to understand the value of freedom and to avoid returning back “behind the walls.” Truly, we determine our destiny when we take advantage of (or don’t take advantage of) opportunities available to us in life. This was my last chance up at bat. I already had two strikes against me. But this time, on the final pitch, I hit a homerun. What I mean by this is that I tried the BLT (Basic Lifeskills Training) Program twice before and failed. For me, the third time was a charm. Finally, I completed BLT with the group called “The Chosen Ones.” Our motto was “They choose to lose. We choose to win.” I, too, decided to win because I was tired of losing, and I wanted to change my way of living. During the six weeks of nonstop hard work—physical training and programming—I pulled myself together and I realized that I had to change. I know that changing isn’t easy, but anything is possible. A person just has to believe in himself and think positively, and be a leader and not a follower. For those who think that change is hard, you are right, it is. But take this as an example, and when you fail something, go back and try again. Don’t quit, because quitters never win and winners never quit. Be positive and believe in yourself, and I guarantee that you’ll make it in life. Always remember that we are only as strong as our weakest link, and the third time can be a charm. Freedom by Christian Alvarez * The Pen is the literary newsletter of Hampden County Jail and House of Correction. 14 winter 2002 Field Notes Behind Bars... Continued from page 11 At the next class, I recruited volunteers for this project from among the more proficient English speakers. This would be an opportunity to be something other than inmates in the eyes of the officers, they could be professionals. I had five students agree to participate. They were not the original students who had developed the earlier training, so we were basically back to the beginning. These students met for four additional classes, which allowed them to do the background research and review the work of the earlier students. We revised the content and divided the responsibilities. Each student had a part of the presentation: Francisco would address the demographics of the jail population, Abad would briefly describe the history and culture of Latinos in America, I would talk about language issues, Jaime would give a glimpse into the Spanish language, and Eutimio and John would both cover the concrete suggestions for the officers. Rehearsal I put the information on PowerPoint transparencies in bullet form, so the presentation would be as professional as possible. In our final meeting before the training, we rehearsed with the transparencies. The students made additions and changes and worked on their transitions, and discourse connectors practiced putting transparencies on the overhead projector correctly and using pointers to indicate place. The students rehearsed their introductions, and gave each other feedback. They tried to minimize those gestures and dialectical features that marked them as inmates: hitching up their jumpsuits, pos- winter 2002 turing with their hands, using double negatives. They tried to identify things “inmate-y” or “cholo.” Abad took some books home, back to the pod, to review the major events in Latin American history. On Monday, the day of the training, we also had our regular ESL class. The five presenters conducted a dress rehearsal with their classmates. Each student was applauded, and the class was focused and attentive. It was obvious tell you that sometimes the officers say, ‘You Mexicans.’ And we think that is racial, and we are not all Mexican.” Abad presented next on history and culture. “When Christopher Columbus—have you heard of him?—discovered the new world, which is what we know now as the Bahamas in 1492, he met the Arawak people, and called them Indians. There were many peoples in this new world, the Toltec, the “Don’t call us the Mexican mafia. That’s racist, and I’m not even from Mexico.” that they had practiced over the weekend. They were comfortable with their transparencies, and as the information was projected onto the whiteboard at the front of the room, the presenters used the board to elaborate on the bulleted points of the slides. The other students were dismissed, and the new officers arrived at the classroom. To our disappointment, there were only three. John made a face and held up three fingers. I whispered that a small group would allow us to practice, and perfect the presentation. We put our game faces on. The students were beautiful, they were funny, engaging, natural teachers. Francisco, aka Manuel, was first. “63% of the Hispanics in this facility are from Mexico. Next we have the United States at 10%, which includes Puerto Rico and people who are citizens, and then Colombia that has 5%, and Republic Dominican 5%, and other countries 10%. So, you can see, not everyone is Mexican. And I want to Olmec, the Aztec in Mexico, and the great Incan civilization in Peru.” He touched on the high points in Latin American history, including the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in which Mexico lost half its national territory to the United States. He went on to describe Latino culture, addressing machismo, family, and religion, among other things. “And, you know, people who came here recently from another country, their attitude toward authority is, well, that authority is corrupt. If you are drunk and driving and the police stop you, well, you give them money and they let you go. We call that the bite.” He talked about variations in the Spanish language: “In Mexico, if you say ‘soy un cabrón,’ you are saying you are ‘the man.’ In Cuba, that means like someone is trippin’ with your wife.” The officers laughed. Continued on page 17 15 Field Notes State of the State—Behind Bars: ABE for the Incarcerated By Bob Bickerton and Jane Brown T he room is bright. Student art and projects cover the walls. Sets of colorful books fill the bookshelves. The video screen is frozen on what appears to be an acrimonious picture—a woman pointing at one of a group of men seated at a table. A whiteboard shows two statements. The students are sitting around four tables, and each group is engaged in intense discussion facilitated by a group leader and documented by two student note-takers. This class shares similarities with many ABE classes in Massachusetts. But look around carefully and you will notice a few unusual features. The students are uniformly neat. Some wear orange costumes; some wear gray, and another wears green. The teacher wears a beeper. You may occasionally see a blue uniformed officer pass by the window. You are observing a class in one of the 13 Massachusetts Department of Education (MDOE) funded ABE instructional programs for the incarcerated. Adult and Community Learning Services (ACLS) of the MDOE is committed to its belief in the value of correctional educational programs. ACLS funds its ABE instructional programs for the incarcerated an approximate $1,300,000 per year. By using both federal and state funding, Massachusetts is able to exceed the 10 percent federal ceiling on this category of funding; in fact, the $1.3 million represents 13.5 percent of our federal ABE allocation. 16 ACLS believes that large numbers of inmates have had scant opportunity to build a useful and law-abiding life: At least half of the incarcerated population does not have the basic skills that would make this possible. Facts About Prisoners and Education Some of the ways in which educational standards of those entering correctional facilities compare with educational standards of the general population are as follows: The National Institute for Literacy states that 70 percent of prisoners are not adequately equipped to perform tasks like writing a letter, explaining an error on a credit card bill, or understanding a bus schedule. It also states that approximately half of all prisoners have not earned a high school diploma or a GED compared with 24 percent of the general population. In October 2000, the Massachusetts Coalition for Adult Education stated that among the Massachusetts 22,000 incarcerated adults and youth, 68 percent demonstrated reading skills below an eighth grade level. Adult Basic Education Decreases Recidivism Based on these statistics, MDOE holds ABE classes in correctional facilities in the belief that those who participate in educational programs while in prison are less likely to become repeat offenders. This belief is supported by the following recent surveys: The MassINC report “From Cell to Street: A Plan to Supervise Inmates after Release” (January 2002) states in its Executive Summary: “Although many rehabilitative efforts have proved disappointing in their lasting efforts, literacy programs are the key exception.” (p. 6) The Office of Correctional Education/Correctional Education Association (OCE/CEA) carried out a Three State Recidivism Study (September 2001) in Maryland, Minnesota, and Ohio. More than 3,000 inmates released from prisons in 1997 and 1998 are reported in this longitudinal study. The release cohort was followed for a three-year period following release from incarceration. This study shows that a large percentage of exinmates will return to prison, but there is one way in which that figure can be reduced: education while inside. Of those who take part in education programs, 43.5 percent will return to prison; of those who do not receive education, 56.7 percent will return. Bob Bickerton is the director of Adult and Community Learning Services at the Massachusetts Department of Education. He can be reached at <rbickerton@doe.mass.edu>. Jane Brown is the program liaison for corrections in Adult and Community Learning Service at the Department of Education. She can be reached at <jbrown@doe.mass.edu>. winter 2002 Field Notes Behind Bars... Continued from page 15 Use Our Names, Please The presentation concluded with Eutimio and John suggesting “do’s” and “don’ts.” “Don’t call us the Mexican mafia. That’s racist, and I’m not even from Mexico. Use our names, please. Don’t disrespect our religion. We have religious figures, and also the Bible is very important to us. Officers when they shake us down, they just throw the Bible on the bed or the floor. We’re in here, but we’re human beings, too.” Eutimio suggested the officers ask the inmates about their culture or language. “These are some suggestions so maybe you can do your job more easy, and we can get along better.” Officers’ Reactions, Students’ Reactions The officers said that the training was useful, and left for their next session. After they left the students were pleased with how things went. John said: “You know, Miss Kristy, I thought with only three of them, it was a joke, but they listened to us and showed respect. It was good.” The audience was small, but the effect on the students was great. It was important enough that Francisco wanted to use his real name, Jaime practiced over and over in his pod, and Abad read additional history. Eutimio said to me afterwards: “You didn’t think we could do so good, did you?” I believed they could do it all along, but maybe they weren’t so sure. For a short time, they were in control and they showed to the few officers, to me, and to themselves just what they could do. This kind of project is effective for language learners on a variety of levels. First, they are identifying issues of importance in their lives and participating in addressing these issues. Second, the learners are learning how to navigate a system in their new country; in this case, the inmates were learning how to effect change in the correctional environment. Third, learners are using language in purposeful ways: to acquire and present information, to educate, and to persuade. A project that engages learners in creating change in their everyday lives can also create power. I will always remember the image of a Latino teacher in an orange jumpsuit and flip-flops, in front of uniformed students with black boots and badges, saying, “Me llamo Francisco Martinez, y yo soy de Mexico.” Kristin Sherman is an instructor in adult ESL at Central Piedmont Community College in Charlotte, NC. She has taught ESL at the Mecklenburg County Jail for five years. She can be reached at <kristin.sherman@cpcc. edu> Prison Voices Program: Voices from Inside Prison Voices is a community outreach program that began as an outgrowth of the Bay State Correctional Center (BSCC) community services program at Norfolk, Massachusetts. The program allows for carefully screened prisoners to meet with small groups of students or members of the community such as high school students, college students, or other interested members of the community. The prisoners speak candidly about their lives, the events that led them to prisons, and what the prison experience has been like for them. This program provides community members with insight into the prison system and other criminal justice issues by providing an alternative information resource. It allows prisoners an opportunity to provide a service to the community while completing the remainder of their sentence. Topics include prison life, peer pressure, substance abuse, education, and other issues. For more information about the Prison Voices program write to Derek Estler or Jaileen Correira at Bay State Correctional Center, PO Box 73, Norfolk, MA 02056, or call them at 508-668-1687, ext 211. winter 2002 17 Field Notes NELRC Notes: Education for Community Participation By Andy Nash O ne of the primary purposes, historically, of adult education has been to prepare people for participation in a democracy. Whether through civics lessons for immigrants seeking citizenship, or reading and writing for emancipated slaves who faced literacy requirements erected to keep them from voting, education has provided access to civic involvement and decision-making. With today’s increasing focus on employment-driven services, however, attention to education for community participation has dwindled. The New England Literacy Resource Center (NELRC) has been working to revitalize this mission ever since 1996, when it launched the Voter Education, Registration and Action (VERA) Project, a non-partisan effort to build the capacity of adult literacy teachers and students to take informed action about community issues. Prompted by the upcoming presidential elections, NELRC disseminated educational materials that helped adults make more informed decisions when voting, understand the structure of government, and address the roles and responsibilities of citizens. In subsequent years, we at NELRC have built on this successful work by exploring opportunities for participation in the civic life of our communities between elections. Our work is rooted in the belief that the adults we work with have valuable insights, talents, and energy to contribute to community efforts, and have a high stake in addressing the problems and policies that affect their lives. We have sponsored projects that help adults develop research, interviewing, advocacy, critical thinking, and public speaking skills as they analyze and express their views about community concerns. Most of the In the coming year, NELRC will continue to be responsive to requests from the field and will continue to develop innovative projects that enhance the ability of people to understand and participate in civic activities. We welcome your ideas in this regard. 18 classroom projects have involved community service, including fundraising for fire victims, volunteering at a soup kitchen, hosting a blood drive for the Latino community, and creating resource materials for peers. Students have also written advocacy letters, spoken before the city council, and organized their neighbors to demand improved services. In 1999, NELRC published the Civic Participation and Community Action Sourcebook (available at <http://literacytech.worlded.org/ docs/vera/index1.htm>) for adult educators, and continues to offer staff and resource development support to the field. The NELRC’s most recent work includes: ◆ Technical assistance with programs that are developing EL/Civics curriculum ◆ Workshops on civics-related topics such as Integrating EFF and EL/Civics or Teaching about the State Budget and Taxes ◆ Ongoing resource development, such as the online Civic Participation and Citizenship collection located at <www.nelrc.org/cpcc/index. htm>or a video guide for the American Friends Service Committee’s soon-to-bereleased Echando Raíces/ Taking Root video about the struggles of immigrants to settle in three U.S. communities. Andy Nash provides professional development and coordinates civics projects through the NELRC. She can be reached at <anash@worlded.org>. winter 2002 Field Notes Department of Corrections in Massachusetts—An Overview By Larry Pollard T he Massachusetts Department of Correction (MDOC) is a state agency that is part of the Executive Office of Public Safety. There are 17 correctional facilities administered by MDOC. On July 1, 2001 there were 10,095 criminally sentenced men and women in the custody of the MDOC. Within the correctional facilities there are many worthwhile programs designed to assist offenders to make a smooth reentry into the community upon their release. Substance Abuse Counseling, HIV Prevention, Chaplaincy Services, Community Volunteers, Parenting Education, and Youth Outreach are just some of the many programs that are offered at the state correctional facilities. Among the most important of these are the academic and vocational programs. Through the efforts of adult educators in the correctional facilities, many exoffenders have been able to improve the quality of their lives by becoming more active and contributing members of their communities, churches, families, and places of employment. The Education Division within the DOC is responsible for administering all of the correctional education programs. All teachers are licensed by the state of Massachusetts and have a minimum of 10 years teaching experience. The mission of the Education Division is to provide incarcerated men and women with the opportunity to acquire and or enhance their academic/vocational capabilities so that they might reintegrate to their winter 2002 community with the least amount of difficulty and become a productive member of their community. It is also a goal of the education programs to decrease the recidivism rate in Massachusetts. Various studies conducted by the Correctional Education Association have shown that inmates who attend education programs while incarcerated have a lower recidivism rate than inmates who chose not to. There are many vocational and education programs available to the incarcerated men and women in the MDOC facilities. The vocational programs available at the institution schools include barbering, culinary arts, welding, building trades, horticulture, Braille transcription, computer repair, and Microsoft Office User Specialist (MOUS) preparation classes. Many of these training programs lead to acquisi tion of a state and/or federal certi- fication or license. Academic classes include ABE, PRE ASE, ASE, ESOL, and life skills. The DOC is also an approved GED Test Center and in March of 2002 the ten thousandth (10,000) GED recipient was recognized at a ceremony held at MCI Framingham. The DOC test center averages 700 examinees each calendar year. The exam is administered at each correctional facility throughout the school year at no cost to the inmates. Unfortunately due to the serious budget crisis experienced by the Commonwealth during this past fiscal year, some education staff members were laid off. In spite of the layoffs, educational services continue to be provided at all the major correctional facilities. Everyone at the Department of Correction’s Education Division is hopeful that many of these staff members will be returned to their instructional positions once the state’s economic situation improves. If you would like more information about the Massachusetts Department of Correction, you may visit their web site at <www.state. ma.us/doc>. Larry Pollard is the ABE director and GED chief examiner for the Massachusetts Department of Correction. He can be reached at <lap7374@ yahoo.com>. 19 Field Notes The Right Thing By Maurice Penn A s an educator who has taught, tutored, and mentored convicted felons on passing their GED, I have thought a great deal about education within prisons. I have dealt with the emotions of those who have failed the GED test—some by the narrowest margin, others, not even close. To me, the real issue is not about education in prisons but what we expect as a society from our correctional facilities and the human beings that are incarcerated within them. No matter what accusation or conviction, no matter if the inmate was falsely accused or actually committed a crime, he or she is still a human being. Human beings have human emotions. So even in the dankest of prisons, you will have people in search of their humanity, their dignity, and even hopes for a better day. Taxing Inmates There have been recent efforts in Massachusetts to tax inmates for their services while locked up. But inmates have no money. All inmate money comes from the outside. It comes from us—those who are not locked up—so actually it’s a back door tax on people who care about our fellow human beings who hap- pen to be incarcerated. Instead of taxing inmates, we need to give inmates the opportunity to think and use their brains in classes while they are locked up. Taking away cigarettes, TV, and weight rooms, and taxing inmates for services are not efforts that promote rehabilitation or reform for prisoners. negative energy will captivate inmates and teach them to become better criminals! Because of this, I think education in prisons should be mandatory, even for lifers. Not counting the few who are framed, most inmates find them selves convicted of an act that they actually did, so they will accept this time of penance; in their hearts Taking away cigarettes, TV, and weight rooms, and taxing inmates for services are not efforts that promote rehabilitation or reform for prisoners. With mandatory sentences, cuts in education programs, and stricter enforcement, we are faced with the issue of the purpose of prison: for rehabilitation and reform or for punishment. Can a person learn while incarcerated? Damn right they can and do. The big question is: What are they learning and who is doing the teaching? If people are not taught the right thing to do and know, then the opposite will happen— people with negative thoughts and they have already convicted themselves. Educational programs help prisoners to better think their way through life rather than react their way through; when they think their way through they are in control, not the Chief Officer, not the warden, and not even the fellow inmates. Maurice Penn is a career counselor/ job developer for an alternative high school program at City Roots, Boston. He can be reached at 617-635-4920. The Massachusetts Adult Literacy Hotline 800-447-8844 20 The Hotline is a statewide information and referral service. It serves adults who seek a basic education program, volunteers who want to tutor, and agencies seeking referrals for their clients. winter 2002 Field Notes Resources on Prisons Web Sites National Institute for Literacy Special Collections: Correctional Education <www.easternlincs.org/correctional_education/> This site is a comprehensive collection of resources for basic skills and literacy programs in correctional education. Through this single access point, instructors, administrators, and adult learners can find activities and links exclusively related to correctional education. Those interested in correctional education can find learning activities, share program administration techniques, join a discussion list, read news about the field, and find links to key correctional education sites. Corrections.com <www.corrections.com/> The Corrections Connection’s (Corrections.com) mission is to provide a comprehensive and unbiased online community for professionals and businesses working in the corrections industry and to “inform, educate and assist” corrections practitioners by providing best practices, online resources, weekly news, products and services, career opportunities, access to post and review bids, partnership opportunities, innovative technologies and educational tools. Film s— Documentaries The following films are available for sale or rental, from First Run/Icarus Films 32 Court Street, 21st floor Brooklyn, NY 718-488-8900 Profits of Punishment Directed by Catherine Scott Produced by Pat Fiske & Paradigm Pictures, 2001 This film looks at prisons as a “new, powerful, recession-proof industry” and explores the relationship between government and industry in the business of incarceration. Ghosts of Africa Directed by Brad Lichtenstein Produced by David Van Taylor and Brad Lichtenstein Narrated by Susan Sarandon, 2001 Ghosts of Attica offers “the definitive account of America’s most violent prison rebellion, its suppression, and the days of torture that ensued.” High Risk Offender A film by Barry Greenwald, 1998 “For ten months, filmmaker Barry Greenwald followed the lives of seven men on the brink of freedom—six deemed at high risk to reoffend—as they struggled to remain on the right side of the law. This film offers a look into the universe of the parole office, and the tenuous relationships between offenders and their parole officers and therapists.” Societies Under the Influence A Film by German Gutierrez A National Film Board of Canada Production, 1998 This film posits the argument that the “morally and politically correct” drug war we read about in our newspapers everyday is a corrupt and pernicious front that protects our judicial system, big business, organized crime, and American foreign agendas. Wearing the Green: Longtermers of the New York State Prison System A Video by Arthur MacCaig, 1994 Former Black Panther Eddie Ellis’s odyssey through New York State’s prison system. Continued on page 22 winter 2002 21 Field Notes Resources on Prisons Continued from page 21 Articles “Participatory Literacy Education Behind Bars: AIDS Opens the Door” Kathy Boudin Harvard Educational Review, Vol. 63, No 2., Summer, 1993, pp. 207–232 Kathy Boudin recounts her story as an inmate and literacy educator at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for women. Lessons in Life The Arts in the Prison Education Curriculum <www.a4offenders.org.uk/content/inc_arts/pages/ incart001.html> This booklet demonstrates the range of ways in which participation in arts activities can contribute to enhanced educational achievement and particularly to improved basic and key skills.It makes a strong statement about the importance of the arts and their position as a valuable aspect of the prison education curriculum. This publication can be viewed online using the links in the Content section or downloaded as a PDF file. Guides “Educating Linguistically and Culturally Diverse Students in Correctional Settings” Virginia P. Collier and Wayne P. Thomas <www.easternlincs.org/correctional_education/teacher _tutor.html> This article looks at considerations for developing appropriate coursework for linguistically and culturally diverse inmates in prisons, in students’ first language as well as English. Coming Home: A Resource Directory for ExOffenders Returning to Greater Boston Communities Prisioners Re-entry Working Group 14 Beacon Street, 6th Floor, Boston, MA 02108 617-523-0555 “Prison Literacy Programs” Sandra Kerka ERIC Digest No. 159, 1995 <www.ed.gov/databases/ERIC_Digests/ed383859.html> This article gives an overview of the contexts and constraints of prison education in the United States. Journals/Magazines Journal of Prisoners on Prison Special Issue on Prison Education <www.jpp.org/editorials/v4n1-cnts.html> Curricula Shakespeare in Jail Martina Jackson <www2.wgbh.org/mbcweis/ltc/alri/shakespeareone. html> “I have visited some of the best and the worst prisons and have never seen signs of coddling, but I have seen the terrible results of the boredom and frustration of empty hours and pointless existence." -former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Warren Burger 22 winter 2002 Field Notes Mark Your Calendar March 25–29, 2003 Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL), 37th Annual Convention: Hearing Every Voice Location: Baltimore, MD Contact: TESOL, 703-836-0774 Web: <www.tesol/conv/t2003/pp/> April 21–25, 2003 American Educational Research Association (AERA), Annual Meeting Accountability for Educational Quality: Shared Responsibility Location: Chicago, IL Contact: John Goss, <jgoss@aera.net> Web: <www.aera.net/meeting> April 26–30, 2003 Commission on Adult Basic Education (COABE), National Conference: Take the Oregon Trail to Quality Programs Location: Portland, OR Contact: Anne Watts, 360-586-3525 Web: <www.ninestar.com/coabe> June 5–8, 2003 Adult Education Research Conference, AERC 2003 Location: San Francisco, CA Contact: Alicia Jalipa, 415-338-1686 Web: <clrml.sfsu.edu/aerc/home.html> June 19–25, 2003 American Library Association (ALA), 127th Annual Conference Location: Toronto, Ontario Contact: ALA, 800-545-2433 Web: <www.ala.org/events/annual2003> Open Issue of Field Notes The summer issue of Field Notes is an open issue. Here’s your chance to submit an article that’s not limited by a specific topic. Would you like to write about a special project, lesson, or material you’ve been working on? Would you like to review a book, video, or web site you have found particularly interesting? Would you like to publicize something your program has done, or highlight accomplishments of your students? June 26–28, 2003 Voice for Adult Literacy United for Education (VALUE), Adult Leadership Institute Location: Tampa, FL Contact: VALUE, 610-876-7625 Web: <www.valueusa.org> Please email Lenore Balliro, editor, at <lballiro@ worlded.org> or call her at 617-482-9485 with your ideas. Submission deadline is April 1. winter 2002 23 Field Notes www.sabes.org/assessment SABES has developed a new Web site to help ABE programs deal with the extensive new student assessment requirements. The site—a virtual user’s guide—provides all basic information, policies, and links in one easy-to-use location. Check it out! Upcoming Issues Upcoming Issues of Field Notes of Field Notes Spring 2003– ABE Licensure Submissions full Spring, 2003– ABE Licensure Summer 2003–Day Open Issue Call by Month. Call bybyMarch 15Day Submit Month. Submit by April 1 Summer, 2003– Issue Title Questions? Email Day Lenore Balliro, Call by Month. editor, at <lballiro@worlded.org>. Submit by Month. Day ◆◆◆ Questions? Email Lenore Balliro, Remember: You can get editor, at <lballiro@worlded.org> PDPs writing for Field Notes ! Nonprofit Nonprofit Org Org U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. PAID PAID Boston, Boston, MA MA Permit Permit 50157 50157 44 Farnsworth Street Boston, MA 02210 Return Service Requested System for Adult Basic Education Support