So You Say You're an Ethical Shopper

advertisement

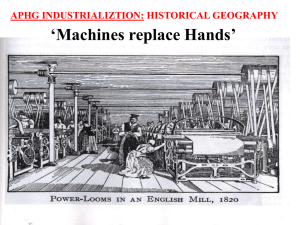

So You Say You're an Ethical Shopper So on Wednesday, I wrote this article for Highline arguing that consumer movements are never going to end sweatshops. The worst conditions are in sub-contractors, small workshops and factories producing for emerging markets. We can lean on multinational corporations all we want, they don't have the information or the power to ensure decent factories, and neither do we. Since the article came out, much of the reaction has been along the lines of either, "Well, I buy my t-shirts from sustainable brands," or "Well, I only buy local." Let me be super clear about this, in words I might have minced in the piece itself: that is impossible. And pretending it's not is exactly what keeps sweatshops from being solved. First, your t-shirt. Let's say it really was produced by an American company, made in the USA, by people earning a living wage, and that wasn't just a marketing ploy to get you to pay more for it. Congratulations. But just because something was sewn together in the United States doesn't mean that's where it's actually from. The vast majority of the world's textiles are produced in India and China. For my article, I asked a CSR manager of an international brand -- you don't wear it, but you've heard of it -- how they monitor textile factories. "Oh we don't," she said. "No one does." And that's not the last layer. Most of the world's cotton is bought and sold like oil, a commodity, consolidated in huge markets in Dubai, zig-zagging through middlemen. It's hard to find out what country it comes from, much less how it was produced. As the Environmental Justice Foundation puts it, "six of the world's top seven cotton producers have been reported to use children in the field." Then there's how it got to you. Shipping is one of the least scrutinized industries in the world. Boats are in international waters, employees work around the clock, they dump weird stuff into the ocean. Who's going to stop them? But let's pretend for a minute. Let's say your t-shirt was produced in a decent factory, with decent textiles and decent cotton, that it came to you on a decent boat. Fine. That is one thing. Think of all of the stuff you buy. Your dental floss. Your furniture. That spatula you bought at the dollar store. You can't choose three or four products where'd like to avoid complicity in forced labor and low pay, and just decide not to worry about everything else. Your coffee might be fair trade, but what about the machine you're brewing it in? Check the bottom, dude; I'll bet five bucks it was made in China. Your car was welded together in Mexico, from iron ore mined in Brazil, smelted in Paraguay. The acetaminophen you take for a headache was produced by a company that keeps poor countries from producing generic medicines for its own people. The point here is not to gloat, or to play the coastal-elite "I'm more ethical than you" game. The point is, you do not have the power or the information to implement your values. None of us want to promote sweatshops or poison tropical rivers. But we all do. No amount of label reading or better buying will escape this fundamental fact. But that's not the point either! The real question is, even if we could buy ethical products, would that improve working conditions in the developing world? In 1750, the Quakers concluded that slavery was an unjust institution and spent the next century advocating to abolish it. Imagine if, instead, they came up with a certification, a commitment that they wouldn't buy clothes made from slave-picked cotton. Think about what a gift that would have been to slave owners. All they had to do was rope off a section of their plantation, hire workers, then charge extra for "slave-free" cotton. It would have been perfect: They make more money, get the Quakers off their back and, the best part, get to keep their slaves. This is how we've spent the past 25 years: Instead of advocating to end the conditions that offend us, we've done exactly the thing that allows them to proliferate. Auditors told me that some factories in China are divided up with thick black curtains. Since brands only inspect the lines making their own products, suppliers can keep conditions however they want in the rest of their factories. This is what you're doing when you buy a fair trade t-shirt or an organic avocado: Concentrating your attention on the tiny corner of the global economy that is not shrouded to you. Instead of raising the floor, you're raising the ceiling. Fair trade allows us to go around bad institutions and let the worst sweatshops remain, rather than take responsibility for the myriad ways in which we reward them. "Many global actors assume there's an institutional void, but there isn't," says MIT's Matthew Amengual. "The state is involved. Positively or negatively, it's there. Rather than transcending local institutions with global rules, we should be trying to work with them." What he means, and what I've seen again and again in the developing world, is that sweatshops don't happen without the participation of their host governments, and they don't get solved without them either. One of the reasons India's garment sector, to take just one example, is so exploitative is that only 2 percent of its textile factories use shuttle-less looms. Without equipment to make them more productive, the only way factories can compete is by extending shifts and keeping pay low. In China, 15 percent of textile factories have shuttle-less looms. The government provides loans and grants, it has deliberately invested in making small factories more productive. India's own Ministry of Textiles boasts that its desperately poor workers are a competitive advantage: "Rising wages and cost of living in countries closely competing with India," says the agency's strategic plan, "provides a vast opportunity for India to capitalize." Domestic systems are decisive, and the lack of them can be devastating. Functioning courts, independent unions, empowered civil society, free media -- this is the stuff that solves sweatshops, not companies with better CSR policies, not improving the performance of just a few factories. Comcast doesn't treat you bad because it's an evil corporation, it does so because it's a monopoly -- because our government allows it to be one. Sweatshops happen for the same reasons. Whenever I go on this little rant in front of my fair-tradey friends, they always give the same response: "Hey, it's better than nothing." I think that's the worst argument ever, but for a second let's entertain the possibility that it's not. If that's our only criteria, there's a lot of other "better-than-nothing" stuff we could be doing instead. Give money to a NGO that helps register unions in the developing world. Sign a petition. Write your senator. Our primary leverage over the developing world comes in the form of market access (bilateral trade agreements, TPP, the World Trade Organization) and financial instruments (the World Bank, the IMF, export credit). Companies lobby to protect their interests in these negotiations, and it's about time we started doing it too. These steps are small, slow, unlikely to leap us to instant improvements. But isn't the argument of the boycotters "If everyone acted like me, things would get better"? Well if everyone put pressure on the institutions that can actually eradicate sweatshops, we might actually solve them. Otherwise, we're just drawing the curtains.