Buy, Sell or Hold? Analyst Fraud From Economic

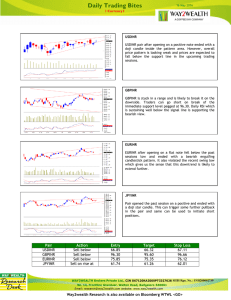

advertisement