Immanuel Kant “The Categorical Imperative”

advertisement

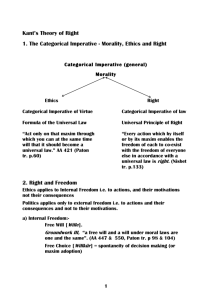

Immanuel Kant “The Categorical Imperative” Kant vs. Utilitarianism: • Utilitarianism: • The previous reading – Morality is fundamentally about the results of our actions. – Acts are morally right if they maximize happiness, wrong otherwise. • In the end, what matters is always/only happiness. • Kant’s moral theory: – Morality is fundamentally about the reasons we have acting. – Acts are morally right if they are done for the right reason. • In the end, what matters is acting freely (that is, acting for a reason rather than because of a cause. A Good Will: Your Reasons for Acting The Good Will: “It is impossible to think of anything at all in the world, or indeed even beyond it, that could be considered good without limitation except a good will.” That is, it is your reasons for acting that make an act good (or bad). “A good will… …is good not because of what it performs or effects, ... But simply by virtue of its volition.” That is, in virtue of the reason for doing it, or the general principle it follows from. “The moral worth of an action… • “… does not lie in the effects expected from it ... – for all these effects ... could have been brought about by other causes... [without] the will of a rational being; whereas it is in this alone that the supreme and unconditional good can be found.” Free Will as Autonomy “Moral worth” requires “the will of a rational being.” • That is, – moral value can be found only in the choices of a being that can act in accordance with reasons or principles, – i.e., in a being that is acting freely. • So, moral worth requires a free will. For Kant, acting freely means … • Acting because of reasons rather than because of causes. – Only “persons” act because of reasons; mere things act because of causes. • Freedom means autonomy: – i.e., being self-legislating, or being the source of the reasons one acts according to. Which Reasons for Acting Have Moral Worth? That is, which general principles should I act upon? • Out of duty: – The only reason for acting that has moral worth is acting because it is the morally right thing to do. • Not out of inclination: – Acting out of inclination (i.e., simply because one wants to act that way) in and of itself has no moral worth. My desires (inclinations): • Are caused by “nature;” – i.e., they are not themselves freely chosen. • So, being free doesn’t require simply acting according to my desires or inclinations, but instead it requires that I choose the principles that I act upon. – One can be a “slave to one’s passions.” • So, to act freely means to act in accordance with general principles (that one chooses); it does not mean acting merely on the basis of your desires (or inclinations). – It does not mean simply doing what you most want to do. What is it to act because it is the “morally right thing to do?” It is To act in accordance with The Categorical Imperative. Imperatives: What you ought to do An Imperative: • An “ought”, an “obligation” • A statement or judgment about what you ought to do. Two kinds of Imperatives: • Hypothetical: – An “ought” that applies to you because of some hypothesis about your goals or desires. – Example: You ought to study hard, if (on the hypothesis that) you want a good grade. • i.e., because you want a good grade (assuming this is true J), it follows that you ought to study hard. • Categorical: – An “ought” that applies to you “categorically,” that is, independently of any hypotheses about your goals or desires. • So, if an imperative is categorical, it’s not hypothetical. – Kant claims that moral obligations are Categorical Imperatives. You: (to me): You ought to stop smoking. Me: Why? You: Because it’s bad for your health. Me: So what? You: Don’t you want to be healthy? Me: Yes. Very much. It’s the most important thing to me. You: Then you should stop smoking! Me: Why? You: Given your desire to be healthy and the fact that stopping smoking will make you healthier, it follows that you ought to stop smoking. Me: I see. Geez, I guess I’ve been a moron. Me: No. Not at all. What I really want is to be sick, miserable, and die young. You: That’s sick! What a crazy thing to want. Me: So, I “ought to” stop smoking only if I want to be healthy. But your hypothesis that I want to be healthy is mistaken. My wants may be "crazy, but my behavior is not irrational. You: I knew you were a moron! Hypothetical Imperatives • The previous example was a hypothetical imperative. – There is an answer to “Why ought I do X?” (Why I ought I stop smoking?) • The answer is because of my wants. – Given the hypothesis that I want to be healthy (and given the fact that smoking is bad for my health), it follows that I ought to stop smoking. It is because I want to be healthy that I ought to stop. – But if I don’t want to be healthy, then this “imperative” (to stop smoking) doesn’t apply to me. Kant: You ought to tell the truth. • Me: Why? • Kant: Because you ought to tell the truth. • Me: I see. What you really mean is given that I want to be trusted, and given that most people don’t trust liars, it follows that I ought to tell the truth, right? (I’m starting to get a “feel” for this philosophy stuff!) • Kant: No. Your obligation to tell the truth is not dependent upon any upon hypothesis about your wants. It applies categorically, i.e., independently of your wants or desires. – (This guy really is a moron!) • Me: Why? How can there be something that I ought to do that doesn’t depend on what is useful in obtaining my wants? • Kant: Good question! That’s exactly what I’m trying to explain! Kant’s Question: • How can there be a “categorical imperative?” – That is, since “imperatives” are obligations, and since moral obligations are not hypothetical; – How can there be moral obligations? • In other words: • How can there be something that I ought to do where this is not because doing so in useful in obtaining my wants and desires? – Why should I be moral? Kant’s Question: • How can there be a Categorical Imperative? – That is, how can there be an “ought” that applies to everyone regardless of their individual wants and desires? • Hint: It has something to do with what it means to act freely— • i.e., to act autonomously— – i.e., to act for a reason. Acting Freely: Acting for a Reason Practical Reasoning: The Logic of Acting According to Reasons • 1) When in circumstance “C,” one ought to do action “A.” – (This is what Kant would call the “maxim” or “volition” of one's action.) • 2) I am in circumstance “C.” • 3) So, I ought to do action “A.” Acting Rationally: • A minimal condition for acting rationally, that is, acting for a reason, is that the “maxim of your action” • (i.e., the general principle you are acting upon) does not contradict itself. But remember… • Practical Reasoning— What it is to “act for reason.” – When in circumstance “C,” one ought to do action “A.” • This is what Kant would call the maxim of one’s action. – I am in circumstance “C.” – So, I ought to do action “A.” • To act freely, – is to act autonomously, • is to act for a reason. • But reasons are always perfectly general. – “When in circumstances “C,” one ought to do “A” applies to everyone at all times. • This is a kind of “universal law.” • So, to act freely is to “will” the “maxim” of your action as a “universal law” that applies to everyone. The Categorical Imperative The First Formulation of the Categorical Imperative: • “Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.” – That is, Act only on those principles you could will (intend) that everyone act upon without thereby contradicting yourself. • What we just said is that whenever you act freely, you are “willing” that your “maxim” should be a “universal law.” – What Kant is saying that we should not act on those principles that it would be contradictory to will that everyone act upon. Acting Immorally means acting Irrationally • Acting morally or immorally requires that we act freely. To freely act immorally is to freely act upon a selfcontradictory general principle. To act upon a self contradictory principle is to act irrationally. It is to act upon a reason that is not a reason. So, to freely act immorally is to freely act irrationally. • This subverts our ability to act for a reason, that is, to act freely. – To freely act immorally is to freely act on the basis of a reason that is not a reason, i.e., to freely act unfreely. • So by acting immorally, we squander our own moral dignity and in so doing treat ourselves as mere things rather than as persons or rational beings. Suppose I choose to lie • What is the general principle I am endorsing? – Kant: What is the “maxim of my action?” – “It is permissible to lie (i.e., to say something false when people expect you to tell the truth) whenever it is convenient to do so.” • When I act freely (i.e., on the basis of a principle), I am endorsing that general principle. – So, when I lie, I am endorsing ( “willing”) the above principle (maxim). But, what am I “willing?” • I am willing that everyone lie when it is convenient. – But, if everyone did this, there would be no expectation of truth telling. • But without the expectation that people will tell the truth, it is impossible for anyone to lie. • So, I am willing that everyone act in a certain way (lying) that makes it impossible for anyone to act that way. – i.e., the principle I am endorsing (the maxim that I am willing) is self-contradictory. So what? • The problem with lying: – Isn’t (just) that it brings about bad consequences. – is that by acting on the principle that everyone lie whenever it is convenient, I am endorsing that principle. • The problem with endorsing the principle that everyone lie whenever it is convenient: – Isn’t that this would bring about bad consequences – is that what I am willing is self-contradictory, • i.e., I am willing that everyone act in a way that makes it impossible for anyone to act that way. So what? • The problem with acting upon a self-contradictory principle: – Isn’t (just) that it’s nutty. – is that I am “squandering” or “abusing” the very feature that distinguishes me from mere things. • Persons have moral dignity because they can act for a reason rather than, like mere things, only because of a cause. – So, if I act upon a self-contradictory principle, I am acting upon a “reason” that isn’t a reason, • because it is self-contradictory. – I am (ab)using my freedom (my ability to act for a reason) to act unfreely. • I am treating myself as a mere thing. The Kingdom of Ends Formulation of the Categorical Imperative: • “Act so that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or that of another always as an end and never as a means only.” • So, persons have a moral dignity that should never be violated. They must never be treated as mere things (as mere means to my ends), but always as having value in and of themselves (i.e., as “endsin-themselves”).