Test 3 Review

advertisement

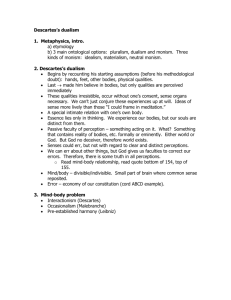

Test 3 Review The Question • What am I? – What sort of thing am I? • Am I a mind that “occupies” a body? • Are mind and matter different (sorts of) things? Descartes’ Answer • What I am is an immaterial soul that “occupies” a material body. • Descartes is a “Substance Dualist” who believes that mind and matter are two irreducibly different kinds of basic “stuff.” – Descartes believes that mental states are not identical to brain states. Descartes • I can conceive of myself without a body, – As a disembodied mind. • I cannot conceive of myself without a mind, – As a mindless zombie. • So, having/being a mind is an essential property, while • Having a body is merely an accidental property. Life After Death? • If there is such a thing as life after death, then there must be a “part” of you that continues to exist after the death of your body. • So, if you believe in life after death, you are already committed to the idea that you are something distinct from your body … – i.e., distinct from any material object. • So, materialists of all varieties must deny the possibility of life after death. Descartes • A Dualist – Descartes thinks that what I am is a mind, and that I occupy a material body. • “Thinking” (being conscious) is an essential property. • “Being extended” (occupying space—having a body) is merely an accidental property. – So, there are two fundamental and distinct basic kinds of stuff: mind and matter. Mind/Body (or Substance) Dualism: There are two distinct, fundamental and irreducible, sorts of things in the world… MINDS • Conscious Beings: – Non-material beings which are the subjects of conscious experience. • Descartes: – Res cogitans – “Thinking” but non-extended beings (beings that do not occupy space). BODIES (Matter) • Material Beings: – Material (“corporeal”) beings that cannot be the subjects of conscious experience. • Descartes: – Res extensa – Extended beings (beings that occupy space), but are not capable of “thinking.” How many kinds of “stuff?” Monism: Dualism: Minds and Matter Materialism: Everything is material Idealism: Everything is mental Des and cartes Lock e Eliminative Materialism Berkel ey There are no mental states, just like there are no ghosts. Identity Theory Mental states are identical to brain states, just like water is identical to H2O. Epiphenomenalism Mental states (qualia) are real but causally inert. Jackson Descartes’ Arguments for Dualism • Bodies are divisible. Minds are not. So they cannot be the same thing. • “Mind” and “Matter” are conceptually distinct —the concept of each is independent of the concept of the other. So, it is possible for one to exist without the other. So, they must be different. A Problem: Causal Interaction • On Descartes’ view (dualism), minds and bodies are fundamentally distinct kinds of things, distinct kinds of “substance.” • And yet, he believes they causally interact with one another. – Exp.: Sense perception, willful action. • But it seems impossible to explain how things with nothing in common could “influence” each other. Carruthers: Mental States are Identical to Brain States • Carruthers turns this problem for dualism into an argument against it (an argument for “the identity” theory). – 1) Only physical events can cause physical events; – 2) Yet thoughts (mental states) can cause physical events (willful action); – 3) So thoughts (and other mental states) must be (must be “identical to”) physical events. Materialism • The identity theory: – 1) Everything that exists is composed of matter, – 2) Mental states exist, but are identical to physical states (brain states), in the way that water is identical to H2O. • Eliminative Materialism: – 1) Everything that exists is composed of matter, – 2) Mental states do not exist. Like ghosts, we once believed they existed, but now we know otherwise. How many kinds of “stuff?” Monism: Dualism: Minds and Matter Materialism: Everything is material Idealism: Everything is mental Des and cartes Lock e Eliminative Materialism Berkel ey There are no mental states, just like there are no ghosts. Identity Theory Mental states are identical to brain states, just like water is identical to H2O. Epiphenomenalism Mental states (qualia) are real but causally inert. Jackson The Identity Theory • Rejects Dualism: a variety of Materialism. • Claims that everything that exists is, ultimately, material. • Unlike Eliminative Materialism, accepts that mental states are, in some sense, “real.” • But claims that what they really are are states of the brain and/or central nervous system. – So thoughts (and other “mental states”) are identical to brain states in just the way that water is identical to H2O. Carruthers and Leibniz’ Law • Carruthers argues that mental states are identical to brain states: dualists disagree. • So, the debate concerns whether or not these things are identical. • Leibniz’ Law states a general truth about identical things: if two things are identical, they have the same properties. – So if things have different properties, they cannot be identical. Carruthers’ Rebuttals • Objection: The Argument from Certainty – I can be certain of mental states, but not brain states. – C: “being such that I can be certain about it” is not a property that things have. • Objection: The Argument from Color – I can have green after-images, but brain states can’t be green. – C: After-images aren’t actually green. Jackson • A “Qualia Freak” – Qualia: What it’s like to smell a rose, etc. • There are “truths” about what it is like to smell a rose, etc. • These are not “truths” of physics. • So, there are truths that are not truths of physics. Jackson’s Dilemma • Jackson recognizes there are truths about what it is like to smell a rose; • And believes that these truths are not truths of physics. • Dilemma: Doesn’t claiming there are truths that are not truths of physics force one into dualism? Doesn’t this force one to reject materialism? Jackson’s Solution • Distinguish (mere) “Materialism” from (what he calls) “Physicalism.” – Materialism: Everything that exists is material. – Physicalism: Materialism plus the claim that all truths are truths of physics. • Jackson is forced to reject physicalism. • But accepting materialism while rejecting physicalism leaves him with Epiphenomenalism. Materialism Physicalism • Everything that exists is composed of matter. • Everything can, in principle, be fully explained in terms of the laws of physics. Epiphenomenalism • Everything that exists is composed of matter. • Not everything can, even in principle, be explained in terms of the laws of physics. – Qualia exist, but cannot be explained in terms of the laws of physics. They are caused by physical events, but do not themselves cause anything. Events in the physical world would be no different without them. How many kinds of “stuff?” Monism: Dualism: Minds and Matter Materialism: Everything is material Idealism: Everything is mental Des and cartes Lock e Eliminative Materialism Berkel ey There are no mental states, just like there are no ghosts. Identity Theory Mental states are identical to brain states, just like water is identical to H2O. Epiphenomenalism Mental states (qualia) are real but causally inert. Jackson Epiphenomenalism • What you get if you accept qualia (truths about what experience is like) while rejecting dualism. • Qualia are real, but causally impotent: they are caused by physical events, but cannot themselves cause physical events. • So, the world wouldn’t be any different if we were all “zombies.” – Consciousness is “real” but doesn’t do anything. Why can’t qualia cause? • According to science, all causes are physical, and so must be describable in the terms of physics. • But qualia, Jackson has argued, cannot be described in the terms of physics. – (Facts about them are not facts of physics.) • So, qualia cannot be the causes of physical events. • Epiphenomenalism is the view that qualia real, but causally impotent. Mental States and Causality The Turing Test • How could we tell whether or not a computer could “think?” How could we tell if it was “conscious?” • Turing proposes a “test,” and says if a computer could pass it, we would have to say that it thinks. – The test involves answering questions in a way that could “fool” us into believing we were talking to a human being. The Issue • Turing’s discussion of the “Objection from Consciousness” helps us understand the core of the issue. • We cannot see “inside” other people’s minds, and yet we believe they are conscious. – So, we must believe this because of how they “behave”— specifically, how they “talk.” – If a computer behaves in the same way, we must either admit that it thinks or deny that other people think, because we use the same “test” in both cases. The Turing Test • Turing believes that if a computer can produce “language” we cannot distinguish from that produced by a human being, then it thinks. • The key point is that we have no direct access to the consciousness of other human beings, and so no direct knowledge of whether or not other human being think. • So, apparently we infer that something thinks by observing its behavior, and the only behavior that is relevant is the use language. • So if computers can produce language we cannot distinguish from that of human beings, we must either deny that either of them thinks (which amounts solipsism), or we must admit that both do. The point is that the evidence is the same in both cases. I Think: Do You? Turing’s Conclusion: • The criteria we in fact use to attribute thinking (consciousness) to other human beings are behavioral. – These criteria concern linguistic behavior—how a think talks, not what it looks like. • If these are the criteria I use with other human beings, it would be inconsistent to demand some “higher standard” of computers. • So, if a computer could meet the same standards of linguistic behavior as do other human beings (i.e., if it could successfully play the imitation game), we must, on pain of inconsistency, claim that it “thinks,” i.e., that it is “conscious.” Good Luck! Think before you answer!