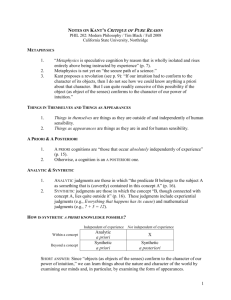

Critique of Pure Reason Immanuel Kant

advertisement