arrateur N R E F L E C T I O N... H O F S T R A N...

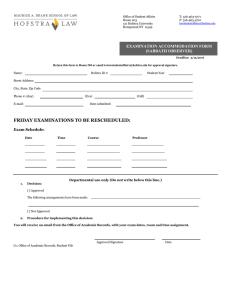

advertisement