Virginia Journal Volume 8 2005

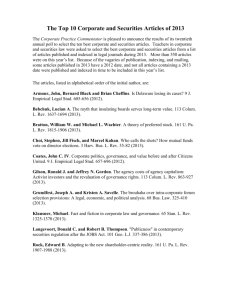

advertisement