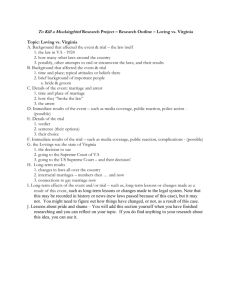

virginia journal abrams choi

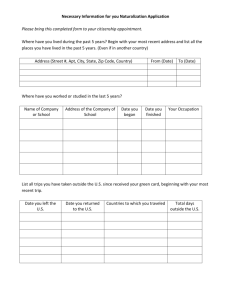

advertisement