THE CREATIVITY EFFECT

advertisement

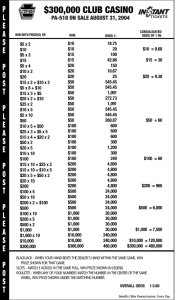

THE CREATIVITY EFFECT Law, Business, Policy, & Education SCHOOL OF LAW Christopher Sprigman, Professor of Law with co-author Christopher Buccafusco, Chicago-Kent College of Law Creators value their works substantially more than would-be purchasers or mere owners. INTRODUCTION Intellectual Property (IP) law is committed to an account of IP valuation derived from the “rational choice” model of neoclassical economics. This account assumes that people engaged in IP markets will rationally value works and inventions and make efficient transfers of rights. Recently, the rational choice model has been challenged by social scientific research showing that owners of goods are often subject to an endowment effect, causing them to substantially overvalue the goods they own. This can lead to higher transaction costs and inefficient markets. QUERY Do endowment effects occur for IP-like goods that are 1) created by the owner and 2) non-rival? HYPOTHESIS Creators will value the works that they create more than either potential purchasers or mere owners of the works. EXPERIMENTAL METHOD We modeled a market for IP rights where the transactions involved only the rents that could be obtained from owning the goods and not the goods themselves. To do so, we created a contest with a known pay-out ($100) for creative works and allowed subjects to buy and sell the right to win the contest prize. We solicited paintings from students at a local art school. The Painters were told that their work would be entered in a contest with nine other paintings and judged by an art expert. The winning painting would receive a $100 prize. Each Painter was told that there would also be a group of Buyers, one of whom would make the Painter a cash offer for her chance to win the prize. The Painters were asked to indicate the lowest amount of money they would be willing to accept to sell their chance to win the prize. The Buyers were recruited from a local university. They were told that 10 paintings had been submitted to a contest for a $100 and that they would have the opportunity to bid on one of the paintings’ chances to win. They were shown a painting and asked to indicate the most amount of money they would be willing to pay to purchase its chance to win the prize. The Owners were also recruited from a local university. They were told that 10 paintings had been submitted for a contest for a $100 prize and that they “owned” one of the paintings’ chances to win the prize. They were told that a Buyer would make them a cash offer for their chance to win the prize and were asked to indicate the lowest amount of money they would be willing to accept to sell their chance to win the prize. All subjects then answered a series of follow-up questions. RESULTS AND IMPLICATIONS This experiment detected a significant valuation anomaly associated with goods that were created by the owner. Creators valued their works substantially more than did either would-be purchasers or mere owners. These results are particularly striking because the goods were both non-rival and incompletely alienated. We call this anomaly the Creativity Effect. The valuation differences between roles seems to be driven almost exclusively by Painters’ and Mean Valuation of Works $80 $74.59 70 60 50 $40.67 40 30 $17.39 20 10 Painter Owner What could be causing these differences? ROLE Optimism, Regret Aversion Buyer PROBABILITY REGRET Painter 52.8% 5.1 Owner 41.9% 3.7 Buyer 31.8% 3.9 All of these differences are statistically significant to p < .01. In ANCOVA analysis with role as a fixed factor and quality, regret, and predicted probability of winning as covariates, the effect of role was highly significant. F (2, 47) = 18.13, p < .0005. All of the groups significantly differ from one another. Painters assign higher values than both Owners (t (33) = 4.11, p < .0005) and Buyers (t (37) = 7.75, p < .0005), and Owners assign higher values than Buyers (t (38) = 3.17, p < .005). Assigned value was significantly correlated with probability (r = .44, p < .01). Additionally, in ANCOVA analysis with role as a fixed factor and quality, regret, and predicted probability of winning as covariates, predicted probability of winning significantly predicted the value assigned to the poem, F (1, 47) = 6.93, p < .05. In ANCOVA analysis of value, with role as a fixed factor and quality, regret, and predicted probability of winning as covariates, regret is very close to being significant (p = .057). Neither emotional attachment nor time spent creating the painting significantly predicted Painters’ valuations. Owners’ excessive optimism about their likelihood of winning the prize. This optimism will likely lead to inefficiencies in markets in creative goods, including IP markets for copyrighted and patented works and inventions. Because we consider these valuations to derive from irrational preferences, we suggest ways in which the law or markets might mitigate their effects. The results suggest consequences for • Preferences for liability rules instead of property rules • Legitimate forms of IP formalities • Royalty-based licensing • Amending the Fair Use and Work-Made-ForHire doctrines Presidential Inauguration Research Poster Competition April 14, 2011 This paper reports the first experiment to demonstrate the existence of a valuation anomaly associated with the creation of new works. To date, a wealth of social science research has shown that substantial valuation asymmetries exist between owners of goods and potential purchasers of them. The least amount of money that owners are willing to accept to part with their possessions is often far greater than the amount that purchasers would be willing to pay to obtain them. Our experiment demonstrates the existence of a related “creativity effect”. We show that the creators of works value their creations substantially more than do both purchasers of their works and mere owners of the works. Further, we provide evidence that these differences are the result of both creators’ irrational optimism about the quality of their work and potentially rational regret aversion associated with selling emotionally endowed property. We conclude by discussing the implications of these findings for intellectual property theory in general and IP licensing in particular.