Document 14106216

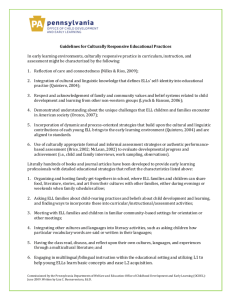

advertisement