In the Supreme Court of the United States Petitioner,

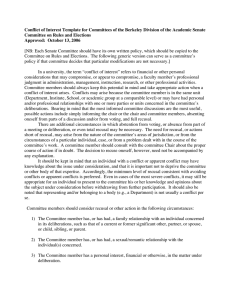

advertisement