In the Supreme Court of the United States No. 13-1487 T H

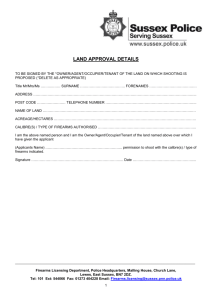

advertisement