No. 13-1487 T H ,

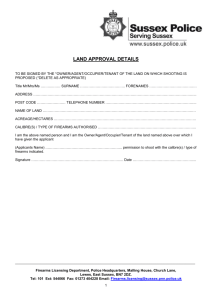

advertisement