Comprehensive Self-Evaluation Report March 2011

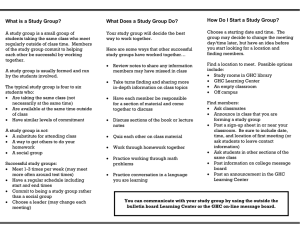

advertisement