Document 14070045

advertisement

J ournal of Ge ronto lo 9,": P SyCHOLOG IC AL SCI EN C ES

1 9 9 5 ,V o l . 5 0 8 , N o . I , P 3 3 - P 4 l

Coptright I995 bt The CerontokNkvl

Stxiei (,1'Aneri(d

Interrelations

of Age, Health,andSpeed

JulieL. Earlesand Timothy A. Salthouse

Georgia Institute of Technology.

Latent construct structural equation modeling of lhe relations among age, self-rated health, and speed was conducted

with two samples, each containing 372 adults betteeen18 and 87 years of age. The major resulti were confirmed in

both samples. Self-rated health, sensory-motor speed,perceptual speed, and reaction time speedall decreaied as age

increased, but health only partially mediated the relationship between age and speed. There were direct elfects of age

on all types of speed in addition to the indirect effects ofage on speed through the self-rated health measurii, and-thire

were direct effects of age on perceptual speed in addition to the indirect effects through sensory-motor speed.

THERE is growing evidencethat speedis an important

r contributorto the declinein cognitiveperformancethat

occursin many taskswith increasedage (c.f., Salthouse,

1992, 1993a).Many reports now exist indicating that the

age-related

variancein a varietyofcognitivetasks,including

some memory tasks,is greatly reducedafter statisticalcontrol ofan indexofperceptualspeed(Hertzog,1989;Lindenberger,Mayr, & Kliegl, 1993;Salthouse,1993a, 1993b;

Schaie,1989).

Although speedappearsto be importantto the relationship

betweenage and various measuresof cognition, relatively

little is yet known about the sourcesof the relationship

betweenageand speed.Healthstatusis one possiblesource,

or mediating factor, becausehealth presumably reflects

biological factorsthat affect speedof processing.Evidence

concerningthe role of healthin the relationshipbetweenage

and cognitive performancehas been mixed. Increasedage

hasbeenreportedto be associated

with declinesin self-rated

healthstatus(Perlmutter& Nyquist, 1990),and self-rated

health status has been found to be related to cognitive

performance,especiallyfor older adults(Field, Schaie,&

L e i n o , 1 9 8 8 ; H u l t s c hH, a m m e r ,& S m a l l ,1 9 9 3 ;P e r l m u t t e r

& Nyquist, 1990).Salthouse,Kausler,and Saults(1990),

however, found that statisticallycontrolling for self-rated

health statusdid not greatly attenuatethe age-relatedvariancein severalcognitivetasks.One possiblereasonfor the

inconsistencyregarding the influence of health in earlier

researchmay be that the behavioralmeasureswere at too

high a level to exhibit direct health-relatedeffects. More

pronouncedrelationsmay be evident with simpler behavioral measuressuchas thosereflectingthe speedof performing elementarytasks.The goal of the presentproject was to

examinethis hypothesisusing structuralequationmodeling

(i.e., LISREL) methods.

Salthouse(1992, 1993a,1993b,1994)distinguishes

between sensory-motorspeed,reflectingthe speedwith which

a personcan perform the sensory-motoraspectsof the task

such as registeringthe stimuli and producing simple responses,and perceptual-cognitive

speed,correspondingto

the speedwith which a personcan perform taskscontaining

elementarycognitive componentssuch as substitutionor

comparison.He found that the relationshipbetweenageand

perceptualspeedwas still significanteven after controlling

for sensory-motorspeed,and that the age-relatedvariancein

severalcognitivemeasureswasattenuatedmoreaftercontrol

of perceptualspeedthan after control of motor speed.This

pattern is consistentwith the view that perceptualspeedis

composedof sensory-motorprocessesplus cognitive processes,

andthatincreased

ageis associated

with a slowingof

both typesof processes.

Becausereactiontime tasksare frequentlyusedto assess

processingspeed, this project also involved two reaction

time measuresin additionto the motor speedand perceptual

speedmeasuresderived from paper-and-pencil

procedures.

The reactiontime measureswere expectedto be correlated

with the other speedmeasures,

but no specificdirectionof

influencewas hypothesizedbecauseof the differentmethods

(i.e., computeradministration

of assessment

of the reaction

time tasksand paper-and-penciladministrationof the other

speedtasks).

If healthstatusdoescontributeto the age-speed

relations,

then it is importantto identify the factorsresponsiblefor this

influence.In two large, population-based

studies,age has

beenfoundto be associated

with an increasein hypertension

and cardiovascular

disease(Dawber, 1980; Mittelmark et

al., 1993).We, therefore,postulatedthat a major determinantofage-related

variationsin healthstatuswascardiovascularfunctioning.

Although the use of medicationto control hypertension

may reduce or eliminate the effects of hypertensionon

cognition(Farmeret al., 1990),many studieshavereported

that hypertensionand cardiovasculardiseaseare negatively

relatedto cognitivefunctioning(Elias,Robbins,Schultz,&

Pierce, 1990; Elias, Wolf, D'Agostino, Cobb, & White,

1993;Farmeret al., 1990;Franceschi,Tancredi,Smirne,

Mercinelli, & Canal, 1982;Hertzog,Schaie,& Gribbon,

1978; Schultz, Elias, Robbins, Streeten,& Blakeman,

1986), and to measuresof perceptualspeed(Boller, Vrtunski, Mack, & Kim, 1911; Light, 1978; Speirh, 1964,

1965). There is also evidencethat speedmay be more

affectedby hypertensionthan are other cognitive abilities

(Shapiro,Miller, King, Ginchereau,& Fitzgibbon,1982;

Wilkie, Eisdorfer,& Nowlin, 1976). Van Swietenet al.

(1991) presentevidencethat hypertensionin older adults

may cause brain damage that causes cognitive decline,

including declinesin speed.We, therefore,postulatedthat

P33

P34

EARLESANDSALTHOUSE

health and cardiovasculardiseasewould partially mediate

the relationbetweenage and speed.

To summarize,the goal of this projectwasto testhypothesized relationsamong age, health status,and severalmeasuresof speed.The datausedin the analyseswere originally

collectedfrom threestudiesreportedby Salthouse(in press).

Becausecompletedatawere availablefroml44 adults,two

separatesampleswere createdto cross-validatethe model

modificationprocess(Breckler,1990).

METHOD

Subjec'ts

Participants

were744 adultsage l8-87 from threeseparate studies. Two hundred and forty-six of the subjects

( 1994)and 258 participarticipated

in Study I of Salthouse

patedin Study 2 of that project. An additional240 subjects

participatedin Study I of Salthouse(in press).All participants were community-dwellingadults recruitedthrough

(requestinghealthy adults) or

newspaperadvertisements

throughcommunitycontacts.They were eachpaid $20 for a

2-3 hour sessioninvolving a battery of cognitive tests

includingthe ones discussedhere. The total data set was

dividedinto two samplesof 372 adults,eachcontaininghalf

of the participantsfrom each study. The mean age of the

i n d i v i d u a l si n S a m p l eI w a s 4 1 . 2 ( S D : 1 6 . 5 ) ,w i t h 1 4 0

subjectsbelow age 40,127 age4G-59,and 105age60 and

above.The meanage in Sample2 was 48.4 (SD : 16.8),

with 127adultsbelow age40, 129 age40-59, and I l6 age

60 and above. Women comprised63.4Voof Sample l, and

60.27oof Sample2. Participants

in SampleI had a meanof

14.4(SD : 2.5) yearsof education,and thosein Sample2

had a meanof 14.7(SD : 2.4) years.

Measures

Only those measuresused in the presentstudy will be

describedhere. (See Salthouse[994] and Salthouse[in

pressl for a completedescriptionof the other tasks.) Five

constructswere measured:self-ratedhealth, cardiovascular

disease,sensory-motorspeed,perceptualspeed,and reaction time speed.(Genderandeducationwerealsoincludedin

initial analyses,but neithervariableaffectedthe age-speed

relations, and thus results with these variablesare not reported.)The variablesare listedin Table l.

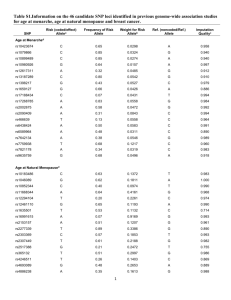

Table l. Descriotionof Variables

Age

H e a l t hr a t i n g I ( l : E x c e l l e n t , 5 : P o o r )

Health rating 2 (l : Excellent,5 : Poor)

Satisfactionwith health1l : High, 5 : Low)

5 Health-relatedactivity limitations(l : High, 5 : Low)

6 Surgeryfor cardiovascularproblems(0 = No, I : Yes)

7 Medications or dietary restrictions for cardiovascular problems

(0:No, l=Yes)

8 Boxes (no. in 30 sec)

9 Digit Copy (no. in 30 sec)

l0 Letter Comparison(no. correct- no. incorrectin 30 sec)

I I PatternComparison(no. correct* no. incorrectin 30 sec)

l2 Digit Digit (reciprocal of median responsetime in msec multiplied

by 10,000)

l3 Digit Symbol (reciprocalof median responsetime in msec multiplied

by 10,000)

vascular(heartor artery)problems?" (0 : No, I : Yes);

"Are you currently taking medicationor under dietary

and

restrictionsfor high blood pressure,or haveyou beentreated

for this condition in the past?" (0 : No, I : Yes).

Sensory-motorspeed. - Sensory-motorspeedwas assessedwith measuresfrom two tests.(Seetop of Figure I for

an illustration.)The BoxesTestwas a paper-and-pencil

test

containing100open(i.e., three-sided)

boxes,with subjects

askedto draw a line to completeeachbox. The scorewas the

numberof boxescompletedwithin 30 seconds.

The Digit Copy Test was alsoa paper-and-pencil

test.The

testpagecontained100pairsof boxeswith a digit in the top

box and nothing in the bottom box. The subjectcopied the

digit in the top box into the bottom box, and the scorewas

the numberof digitscopiedin 30 seconds.

Perceptualspeed.- Perceptualspeedwas assessed

with

the two testsillustratedin the bottom of Figure I . The Letter

ComparisonTestcontained2l pairsof letterstringswith 3,

6, or 9 items in each string. If the letter strings were the

same,the subjectwasto write an S on the line betweenthem,

and if they were different (i.e., a changein the identity of

one letter in one memberof the pair), a D was to be written

on the line. Thirty secondswere allowedfor the test, and the

scorewas computedby subtractingthe numberof incorrect

Health. - Four measuresof self-ratedhealth were obresponsesfrom the numberof correctresponses,in order to

tained. A paper-and-pencildemographicsquestionnaireincorrectfor guessing.

cluded three health questions, similar to those used by

The PatternComparisonTest was similar to the Letter

Krause(1990), that were to be answeredusing a 5-point

ComparisonTest, except that the to-be-comparedstimuli

scale.Thesewere: "In general,how satisfiedare you with

were pairsof line patterns.The test pagecontained60 pairs

yourhealth'?"(I : High,5 : Low); "How would you rate

of line patternswith 3, 6, or 9 line segmentsper pattern,and

your healthat the presenttime?" ( I : Excellent,5 : Poor);

30 secondswere allowedto work on the test.The taskwas to

"How

and

muchareyour daily activitieslimited in any way

decideif the pairs were the sameor different (i.e., a change

problems?" ( I : High, 5 :

by your healthor health-related

in the identity of one line segmentin one member of the

Low). Participantsalso ratedtheir healthon a 5-point scale

pair), andto write an S (for same)or a D (for different)on the

(l : Excellent,5 : Poor)in acomputer-administeredtask. line betweenthem. The score was the number of incorrect

responsessubtractedfrom the numberof correctresponses.

CardiovascuLardisease.- The demographicsquestionnaire also includedtwo questionsabout cardiovasculardisReactiontime speed.- Two measuresof reactiontime

ease.Thesewere: "Have you ever had surgeryfor cardiospeedwerealsoobtainedfrom eachresearchparticipant.(See

AGE, HEALTH, ANDSPEED

BOXES

P35

DigitDigit

DIGITCOPYING

DigitSymbol

r f L _ i r -Er rE E E EEBHHBHBHB

EHHEHBEH

l n l l-l l

Ert

EI

f f n l IJ EEEEE

E

N

t-t LI f IJ l

l

nI

l

IJ

EEEEE

EEEEEH

*

;

NO

(zl

YES

(n

Figure 2. Illustrationof sampledisplaysin the reactiontime tasks.

PATTERNCOMPARISON

M_tr

tr_tr

tr_tr

tr_tr

w_g

LETTER

COMPARISON

Bl(\/

BKP

DRSPQ- DRSPQ

MJDWPL-

MJDSWPL

JWS-JXS

XFLKM- XFLKM

QWZPLNV QWZPLNV

Figure l. Samplesof paper-and-pencilspeed tasks. The top two tests

were postulatedto assesssensory-motorspeed,and the bottom two tests

perceptualspeed.

Figure2 for an illustrationof a sampledisplayin eachtask.)

In the Digit Digit Test, a redundantcode table conraining

pairsof identicaldrgitswas presented

at the top of the screen,

and a probestimuluscontaininga pair of digits was presented

in the middleof the screen.The subjectpressedthe "i " key if

thedigits matchedandthe "2" key if thedigitsdid not march.

Eighteenpracticetrials were followed by 90 experimental

trials(i.e., I 0 with eachdigit).Because

average

accuracywas

over95Vo,the dependentvariablein both reactiontime tasks

wasthe medianresponse

time in msec.

In the Digit SymbolTest,thecodetablecontainedpairsof

digitsandsymbols,andtheprobestimuluscontaineda digitsymbol pair. If the digit and symbol matchedaccordingto

the code table, the subjectpressedthe "/" key, and if they

did not matchaccordingto the code table then the "2" key

was pressed.As in the Digit Digit task, l8 practicetrials

precededthe 90 experimentaltrials.

Procedure

Participantswere tested in a single sessionat mutually

convenientlocationssuch as a college campus, churches,

or homes.The order of presentationfor the tasksconsidered

in the presentanalysiswas: Questionnaire,

Boxes, Letter

Comparison,PatternComparison,Digit Copy, Digit Digit,

Digit Symbol.

Rr,sulrs

The mean,standard

deviation,kurtosis,andskewforeach

variablein eachsamplearepresentedin Table 2, andthe correlationmatricesarecontainedin Table3. Kurtosisandskew

valuesare reportedto test the assumptionof multivariate

normality.Kurtosisestimateswerebetween-1 .03 and2.14

for all measuresexcept the cardiovasculardiseasesurgery

measure,Digit Digit, andDigit Symbol.The Digit Digit and

Digit Symbol reactiontime variableswere transformedby

takingthe reciprocaland multiplyingby 10,000in orderto

decreasethe kurtosis and skew of the measures.therefore

increasingnormalityof the distributions.After the transfbrmation,the Digit Digit variablehad a kurtosisof -.09 and a

skewof -.46 for SampleI anda kurtosisof -. l4 andskewof

-.25 for Sample2. The Digit Symbolvariablehada kurtosis

of .46 and a skew of .45 for SampleI and a kurtosisof .01

and skew of .34 for Sample2. Becausethe measuresof

cardiovascular

diseaseweredichotomousand had high kurtosis,this constructwas not usedin the initial model.

Estimatesof the reliabilitiesof the speedmeasuresare

containedin Table4. The immediatereliabilitieswerebased

on conelationsbetweenalternateformsof the testsadministeredin the samesessionfor the 240 adultsbetweenl8 and

82 yearsof age in Study I of Salthouse

(in press).The twomonthreliabilitieswerebasedon a sampleof 39 olderadults

(58 to 80 yearsof age) who were re-administeredthe same

testsapproximatelytwo monthsafter the original testing.

Age Relations

In orderto illustratethe agetrendsfor the speedmeasures,

all measureswere convertedto z-scoresand plotted as a

function of age decadein Figure 3. Nonlinear age effects

were examinedin multiple regressionequationswith quadratic Age and cubic Age terms enteredafter the linear Age

term. Noneof the nonlineareffectsweresignificant(p < .01)

for any of the measuresin Sample l, but the quadraticAge

term was significant(andpositivein direction)for the Boxes,

Digit Copy, and Letter Comparisonmeasuresin Sample2.

Becausethe higher-ordereffects were restrictedto a few

measuresin one sample, and were associatedwith rather

smallincrements

in variance(i.e., l.5Vofor Boxes,5.4Vofor

Digit Copy, and 3.37o for Letter Comparison),only linear

ageeffectswere consideredin subsequent

analyses.

P36

EARLESANDSALTHOUSE

Table2. Summary

Statistics

Sample I

Variable

Mean

SD

l.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

I l.

12.

13.

/1

r6 . 5

0.97

0.88

0.84

0.87

0 .l 8

0.39

13.8

lt.4

3.3

4.0

281

446

Age

Health Rating I

Health Rating 2

Health Satisfaction

Health Limit

Surgery

Medications

Boxes

Digit Copy

Letter Comparison

PatternComparison

Digit Digir

Digit Symbol"

1

2.09

2.31

2.34

1.56

0.03

0 .r 9

48.8

51.2

9.9

15.5

822

I 636

Sample2

Kurtosis

Skew

Mean

- 1.03

-0.32

-0.26

0.65

2.t4

26.4

0.64

0.41

-0.02

t.ll

0.51

6.88

t.34

0.29

0.62

0.30

0.51

I.61

5.32

t.62

0.22

-0.21

-0.29

0.47

2.30

r.06

48.4

2.07

2.27

a

1A

1.59

0.05

0 .l 5

48.3

52.0

l0.l

15.6

791

l6t2

- 1.03

- 0 .l 3

-0.30

0.66

1.78

I3 . 8 6

I .75

0.02

0.66

0.79

- 0 .l 6

5.98

t.37

16.8

0.96

0.90

0 . 8l

0.86

0.23

0.36

1 3 I.

10.5

3.4

4.3

235

442

0.05

0.65

0.32

0.50

1.48

3.97

1.93

0.06

-0.43

-0.06

o.42

2.08

1.08

Nrle. Skew and Kurtosiswere computedusing SAS.

"ValuesreDo(ed are for medianreactiontimes in msecbeforethe transformationdescribedin Table I

Table 3. CorrelationMatricesfor Sample I (abovediagonal)and Sample2 (below diagonal)

l0

I

2

3

4

5

6

l

8

9

IO

I I

t2

l3

.19

.09

.t2

.o7

.21

.25

.29

^<

-.45

- .38

-.56

-.49

-.58

.20

.12

.15

.69

.79

. )-J

_):)

t1

.zJ

-.19

-.t5

-.08

-.09

-.14

-.t2

.22

.28

-.18

-.09

ta

ta

-.15

.t4

.65

.80

.54

.15

.21

-.16

-.09

-.02

-.04

- . 1I

-.10

1^

.51

.55

.54

.22

.26

_.15

_ .t 5

-.I8

-. L-)

1a

1^

.06

.01

.02

.00

.02

.29

.24

. z-t

.t7

.16

.l l

.30

-.t4

-.21

-.t4

-.08

-.14

-.t7

_10

*.26

-.28

t l

aa

.01

-.24

-.18

t l

-.20

-.25

-.26

11

-.47

-.29

- .30

ta

a1

.65

.o/

.J:)

.50

.45

.44

.46

.55

ll

*.45

aa

-.25

_.19

-.I8

-.03

11

.45

.56

.50

.36

.47

- ./-)

l2

t3

< )

57

1t

11

a l

-.13

-.24

-.09

a2

.49

.51

.59

5l

60

l)

f1

-.20

-.07

-.27

.31

.39

.50

.54

-.22

-.04

-.29

.38

.42

.59

.61

11

.72

ly'ote:Numbersofvariables correspondto thosein Table l. All correlationswith an absolutevalue greaterthan. l3 were signiticantly(p < .01) different

from zero.

Table 4. Reliabilitiesof SpeedMeasures

lmmediate

Boxes

Digit Copy

Letter Comparison

Pattern Comparison

Digit Digit Time

Digit Symbol Time

.86

.86

.58

.61

.93

2-Month

measureof overall fit that takes into account the degreesof

residualis basedon the

freedom, and the root-mean-square

averageof the unexplainedresiduals.

.t-,

.70

.71

.64

.85

Nole.' Immediatereliabilities are correlationsbetweenalternateforms.

Two-month reliabilitiesare test-retestreliabilities.

CovarianceStucture M odeling

The varianceicovariance

matrix was analyzedusing the

LISREL VII maximumlikelihoodestimationprocedure.For

each model the chi-squarevalue, degreesof freedom, pvalue,adjustedgoodness-of-fitindex, androot-mean-square

residualare reportedas suggestedby Raykov, Tomer, and

(1991).The adjustedgoodness-of-fit

Nesselroade

indexis a

MeasurementModel

A model with four factors (health, sensory-motorspeed,

perceptualspeed,and reactiontime speed)was fit to the data

from Sample I by allowing covariancesamong all of the

factors. The residual variancesof the measureswere also

estimated,but the residualcovarianceswere fixed at zero.

The fit of this model(i.e., Ml) wasadequate,

as indicatedin

Table5.

Age was then addedto the model. As in the first model

(i.e., M l), all of the factorswere allowedto intercorrelate.

The residual variances were estimated, but the residual

covarianceswere setto zero. As can be seenin Table 5, this

model (i.e., M2) alsohad a satisfactoryfit. Thus the hypothesizedfactor structurefit the dataadequately.

Standardizedcovariancesamong health, speed,and age

are in Table 6. It can be seen that ase is associatedwith

P37

AGE, HEALTH, AND SPEED

Sample2

Sample1

t'5

Bon

4tDlglpop'

1

Commbon

Paltern

,...o.,;.

o.

IrECotnFbdr

"o

tb

E

o

8

:'.:t

o

K.*r=,.

o.5

D'ql{,Fr

s'\

--

)?

Dlglt SyFbol ff

-N.--

o

o.' t \

*l

.t

-'-./

1..'-.-r'

'rN

.i\

.lr'b

-1.5

-1.5

n

3

o

4

{

l

5

o

d

t

7

o

8

o

z

'

'

E

)

/

o

s

o

q

)

7

o

o

o

Chronological

Age

Age

Chronological

by between39 and ttl individualsin each

Figure 3. Mean z-scoresby decadefor the six speedmeasuresin the cunent prolect. Eachdecadeis represented

samole.

Table 5. Summaryof Model Fitting for Sample I

Model

Description

X'

df

;;-value

AGFI

RMR

Ml

M2

NI

lnterconelatedfactor structure

Addition of age

Null model

40.48

54.51

732.56

29

35

4s

0'76

.019

000

.960

.952

.549

382

191

I 8.25

Sl

Basic model (seeFigure 4)

Compareto M2

Compareto N I

Add direct path from Health to Pspd

Compareto S I

54.51

0.0

678.05

36

I

9

.953

793

5 4 . 5|

-15

.952

.191

0.0

|

025

>.01

<.01

0l9

>.01

.9-56

.949

.576

.321

.67|

15.55

52

After Addition of CardiovascularDiseaseFactor

M3

M4

N2

factorstructure

Intercorrelated

Additionof ase

Null model

58.38

73.23

808.31

44

5l

66

53

Basicmodel(seeFigure5)

to M4

Compare

Compare

to N2

Add directpathfromAgeto Health

C o m p a rt o

e5 3

Add directpathfromHealthto Mspd

to 53

Compare

AdddirectpathfromHealthto Pspd

to 53

Compare

Add directpathfromHealthto RTspd

to 53

Compare

Add directpathfromCVD to Pspd

to 53

Compare

78.60

5.3'7

729.71

15.36

2.13

76.'71

3.48

78.59

5.36

78.36

5.13

78.40

5.1'7

56

5

l0

55

I

55

I

55

I

55

I

55

I

54

55

56

57

58

.O'72

.022

.000

.025

>.01

<.01

.036

>.01

.028

>.01

.020

>.01

.021

>.01

.021

>.01

.950

.665

.952

.666

.950

.677

.949

.664

.950

.665

.950

.657

Nores: AGFI : adjustedgoodness-of-fit index; RMR : root-mean-squareresidual; CVD : cardiovasculardisease;Mspd : sensory-motorspeed;Pspd

= perceptual speed;RTspd = reaction time speed.

P38

EARLESAND SALTHOUSE

Table 6. InterconelationsAmong Age, Health, and Speed

Factor

Mspd

Pspd

RTspd

Health

CVD

Age

Mspd

.80

.62

Pspd

RTspd

.80

.54

.85

.81

11

-.41

_.43

.67

Health

-.3u

2 l

2f

-.19

,.16

-.o-1

.47

.t2

CVD

Age

-.43

-.43

.44

.33

-.54

, .61

-.64

.22

.40

.48

Nolcs. Standardizedcovariance estimatesof the linal nteasurement

rnodelfbr Sample I (abovediagonal)and Sample2 (below diagonal).CVD

= cardiovasculardisease:Mspd : sensory-motorspeedlPspd - perceptual speed:RTspd - reactiontime speed.

slowerspeedand lower self-ratedhealth,and thatthe speed

measures

havehigh positivecorrelations

with eachother.

StructurulModel

The basichypotheses

to be testedwerethatthereis a direct

eff'ectof age on self'-assessed

health,and that healththen

influencessensory-motorspeed,which in turn influences

perceptual

speed.Directeffectsof agewerealsoexpectedon

a l l t h r e es p e e dm e a s u r e sT.h i s s t r u c t u r ar ln o d e (l i . e . , S l ) i s

shownin Figure4. The variances

of the f'actorsas well as of

the indicatorswere estimatedby the model. Two covariancesbetweenfactorswere also estimated(i.e., sensoryrnotorspeedwith reactiontime speed,and perceptual

speed

with reactiontime speed).All other covariancesbetween

fackrrs and between indicators were tixed at zero. The

loadingof one indicatorof eachf'actorwas fixedat one ( i.e.,

Digit Copy, PatternComparison,Digit Symbol,and Health

Rating 2). It can be seenin Table 5 that the model had a

satistactoryfit, and did not differ significantlyfiom the

measurement

model(i.e., M2). The additionof a directpath

from healthto perceptualspeed(i.e., 52) did not significantly improvethe tit of the model.The basicmodel (i.e.,

S l ) l i t s i g n i f i c a n t lbye t t e rt h a nd i d a n u l l m o d e l( i . e . , N I ) i n

which all pathsbetweenlatentconstructs

werefixedat zero.

-['he

Figure4.

structuralntodcl. Paramcterslirr SarnpleI arc on the leli.

a n d t h o s el i r r S a n r p l c2 a r eo n t h e r i - u hitn p a r e n t h e s e P

s .a t hc o e l l i c i e n t a

s re

l r o m L I S R L , L ' sc o n l p l e t o l ys t a n d a r d i z esdo l u t i o n .A l l p a t h sa r e s i g n i f i c a n t

a t I < . 0 1 c x c c p tl i r r t h e p a t h sl i o m a g et o h e a l t ha n d h e a l t ht 0 R 1 ' s p dl i r r

S a n r p l e2 . w h i c h a r es i g n i t i c a nat t 2 < . 0 5 .

-->

?4(4s,

0s (.29)

A-)

Age

N6

(-so)

\,r,or, \

|

l-.se \r-.2

-")

/-'e

2 7\ ' 1

Additi on tl Cardiovascular D i sease

I

.78l.7s

RTspd

Measurementmodel.- The cardiovascular

diseasefactor

wasthenaddedto the model.This is a weakconstructin the

currentprojectbecauseit wasassessed

with two dichotomous

variablesin which the numberof non-zerovalueswas small

(i.e., l2 for surgeryand 69 for medicaltreatment).

Furthermore, the surgerymeasuredid not load significantlyon the

cardiovasculardiseasefactor. Nevertheless.the intercorre(i.e., M3 in Table 5) had a satisfactory

latedfactor-structure

fit, as did the factorstructureincludrngage(i.e., M4).

Structural model. - The basic cardiovasculardisease

m o d e l( i . e . ,5 3 ) i s s i m i l a rt o t h eb a s i ch e a l t hm o d e l( i . e . ,S l )

and is illustratedin Figure 5. The only differencefrom the

basic healthmodel (i.e., Sl) is that the effectsof age on

healthand the effectsofhealth on speedare hypothesizedto

be mediatedby cardiovascular

disease.As can be seenin

Table 5, this model fit the datawell. It is not significantly

worsethanthe measurement

model(i.e., M4), and it is sig-

ogtr

95(.93

Dr9tr

:.46 (-.22)

surecry{

CVD

vcos

4

49 (.44)

H.Cth R.t. 2

Adth

Umit

Figure5. The structuralmodel includingcardiovascular

disease.Parameters lbr Sample I are on the left. and thosefbr Sample2 are on the right in

parentheses.

All paths are significantat p < .01 except fbr the loading of

surgeryon CVD. the pathfrom ageto Mspd. andthe covarianceof Mspd and

RTspd for Sample I . The path from ageto Mspd is significantat p < .05.

AGE, HEALTH.ANDSPEED

nificantlybetterthan a null model (i.e., N2) in which all

pathsbetweenlatentconstructswere fixed at zero. The only

path that was not signilicant was the covariancebetween

sensory-motorspeedand reactiontime speed.Furthermore,

the pathfrom ageto sensory-motorspeedwas significantatp

< . 0 5 b u t n o t a tp ( . 0 1

The additionof a directpathfrom ageto health(i.e., 54 in

Table 5) did not significantlyimprovethe fit of the model.

The additionof direct pathsfrom healthto the speedfactors

(i.e., 55, 56, and 57) alsodid not significantlyimprovethe

model.Finally, a directpathfiom cardiovascular

diseaseto

perceptualspeed(i.e., S8) did not significantlyimprovethe

model. It can thereforebe concludedthat the model portrayed in Figure 5 cannot be substantiallyimproved by the

additionof omittedpaths.

Cross-Validation

Followingthe recommendations

of Breckler(1990), the

resultsof Sample I were cross-validated

using Sample2.

The samesequenceof model modificationsusedfbr Sample

I was usedto testthe modelsfirr Sample2, with the results

s u m m a r i z e idn T a b l e7 . T h e b a s i ch e a l t hm o d e l( i . e . . S l )

and the basiccardiovascular

diseasemodel(i.e., 53) fit the

data well. As with Samplel, no additionsto eithermodel

significantlyimprovedthe fit of the model.

Examinationof the coeflicientsin Figures4 and 5 reveals

that the patternof relationswas quite similar in the two

samples.The strengthof someof the relationsvariedacross

P39

samples(e.g., Sensory-MotorSpeedwith ReactionTime

Speed, PerceptualSpeed with ReactionTime Speed, and

Age with Health),but the discrepancies

arequiteminor.

Reg,ressktn

Analyses

An additionalanalyticalmethodwas usedto confirmthe

inferencesabout the relative influence of health on agerelateddifferencesin speed.The methodconsistedof using

hierarchicalmultipleregression

equationsto determinethe

proportionof age-relatedvariancein the composite(average

of z-scores)speedmeasurebefore and afier control of the

composite(averageof z-scores)healthindex.The variance

estimatesfor the compositesensory-motor

speedindex before and afier control o1'the compositehealth index were

. 2 2 1a n d . l 6 8 r e s p e c t i v e fl yo r S a m p l eI , a n d . 2 4 5 a n d. 2 2 2

respectively

for Sample2, whichcorrespond

to reductions

of

26.6Vcin Sample I and 9.4c/oin Sample2. Comparable

valuesfbr the compositeperceptualspeedindex were .326

a n d . 2 7 2i n S a m p l el , a n d . 2 9 3a n d . 2 1 6i n S a m p l e2 , t b r

reductionsof 16.6o/c

Valuesfbr the

and 5.tlolc,respectively.

compositereactiontime speedindex were .302 befbrecontrol of healthand .250 after controlof healthin Samplel,

and .294 and .270 betbre and afier control ol' health in

Sarnple2, which correspondto reductionsof 11.24/oand

8.27c, respectively.It is apparentfiom theseresultsthat

between l3o/c and 94o/cof the age-relatedvariance in the

compositespeedmeasureswas independent

of the health

measures.

Table7. Summaryof Model Fittinglbr Sample2

Description

dt

/)- va I ue

AGt-t

RMR

MI

M2

NI

I n l e r c ( ) r r e l a l el rdc t ( ) r\ t r u c l u r (

A d d i t i o no f a g e

Null model

59.62

65.62

669.02

79

35

4-5

00I

.001

.000

.943

.944

.572

.50u

.u63

l rJ.20

SI

Basic model (seeFigure4)

Corrpare to M2

Compareto N I

Add direct path fiom Health to Pspd

Conrpareto S I

65.97

.35

603.05

65.62

.35

-1t)

.002

>.01

<.01

.001

>.01

.94-5

.ttTtt

I

9

35

I

.941

.u63

S2

Alier Addition of CardiovascularDiseaseFactor

ti0.3u

M3

M4

N2

lntercorrelatedlactor structure

Addition ol'age

Null model

89.U4

113.10

44

5l

66

.001

.00r

.000

942

939

590

..12ti

. 75 9

15.5t

S3

B a s i cm o d e l( s e eF i g u r e5 )

Compareto M4

Compareto N2

Add direct path liom Age to Health

Compareto 53

Add direct path from Health to Mspd

Compareto 53

Add direct path from Health to Pspd

Compareto 53

Add direct path from Health to RTspd

Compareto 53

Add direct path fiom CVD to Pspd

Compareto 53

95.97

6 .r 3

677.73

91.64

4.33

94.7t)

t.2l

95.72

.25

9 5. 7 1

.26

95.91

.03

56

-5

l0

5-5

I

55

I

55

I

55

I

55

I

.00|

>.01

<.01

.001

>.01

.001

>.01

.001

>.01

.001

>.01

.001

>.01

910

.{339

942

.824

940

.173

940

.833

939

.845

939

.840

S4

S5

S6

S7

S8

Notes..CVD = cardiovasculardisease:Mspd = sensory-motorspeed;Pspd : perceptualspeed:RTspd : reactiontime speed

P40

EARLESANDSALTHOUSE

DlscussroN

Both healthandspeedwerefound to vary with age,but the

age-speedrelationswere only weakly mediatedby health.

This is consistent

with the resultsof Salthouse

et al. ( 1990).

who found only weak mediationby healthof age-cognition

relations.Evenwith a very basicability (i.e., the speedwith

which elementaryoperationscan be executed),therefore,

healthdoesnot accountfor a largeamountof the age-related

variancein performance.Although healthdid havea moderate effect on sensory-motorspeed,all of the effectsof selfratedhealthon perceptualspeedwere indirect and mediated

throughsensory-motorspeed.

Becausesubstantialdirect effects of age on speedwere

evidentin additronto the effectsmediatedby healthstatus,it

can be concludedthat factors other than self-ratedhealth

statusare responsiblefor much of age-relatedslowing in

relativelyhealthyadults.It is possiblethat,as Birren(1965;

Birren, Woods, & Williams, 1979) has suggested,agerelatedslowingis a manifestation

of primary aging, and is

relativelyindependent

of disease.The relationsthatdo exist

betweenself-assessed

health statusand measuresof speed

could:(a) reflectweakcausalinfluences

of healthon speed;

(b) be a consequence

of a common influenceof biological

statuson both setsof variables,or (c) represent

an effectof

basingthe ratingof one'shealthat leastpartiallyon assessmentsof one'sspeedof perfbrmance.

Obviously,additional

researchis neededto distinguishamongthesealternatives.

An important featureof the current project was that (as

recommended

by Breckler, 1990)the model modification

procedurewas cross-validated

in an independent

sampleto

decrease

the likelihoodofcapitalizationon chance.Because

the samepatternof resultswas evident in two moderately

large samples,the reportedrelationsappearquite robust.

The hypothesized

modelfit thedataadequately,

andtheonly

significantproblemoccurredwhen the cardiovascular

diseaseconstructwas addedto the model. This constructwas

weak in the current project becausef'ew subjectsreported

cardiovascular

problems,and the indicatorsdid not load

highly on the factor.

There are severallimitationsconcerningthe mannerin

which healthwas evaluatedin this project.First, one can

questionthe validity of self-reportedhealth status as a

measureof objectivehealth.However, it shouldbe noted

that self-ratedhealth has been found to relate to physician

(LaRue,Bank,Jarvik,& Hetland,1979),numassessments

ber of prescriptionmedications(Salthouse,Kausler, &

Saults,1990),andlongevity(Botwinick,West,& Storandt,

1978; see page 59 in Salthouse(1991) for more relevant

citations).Thus,althoughself-ratings

providea muchcruder

evaluationof healthstatusthan do physicianassessments,

they are relatedto more objectivemeasuresof healthstatus.

Second,an attemptwas madeto recruit only healthyvolunteers, and hence the range of health was undoubtedlyrestrictedrelativeto the generalpopulation.Thus the resultsof

the current study can only be generalizedto the relatively

healthy adult population.Nevertheless,becausesignificant

negativeage relationswere found with both the health and

speedmeasures,an opportunitydid exist for at least some

mediationalinfluence.

Although the results with the cardiovascularconstruct

must be consideredtentativebecauseof weak assessment

of

this construct, cardiovascularstatusmay be an important

factorin the negativerelationsbetweenageand self-reported

health status,and betweenself-reportedhealth and speed.

Previousresearchsuggestedthat cardiovasculardiseasewas

relatedto both perceptualspeed(Speith, 1964)and higher

cognitivefunctioning(Hultschet al., 1993).In the current

study, almost all of the effects of health on sensory-motor

speedwere mediatedby cardiovasculardisease,suggesting

that cardiovasculardiseasemay be the aspectof healththat

contributesto the negativerelationsbetweenage and speed.

This interpretation,however,needsto be investigatedmore

directly with more sensitiveandobjectivemeasuresof health

and cardiovascularstatus before it can be acceptedwith

confidence.

In summary,self-ratedhealthand speedwere both negatively relatedto increasedage. However, healthonly partially mediatedthe age-relatedvariationin speed,and much of

the relationthat did exist betweenhealthand speedappears

to have been mediatedby cardiovascularstatus.The major

conclusionfrom theseanalysesis that,within this relatively

healthysampleof adults,healthstatuswas associated

with

only a relativelysmall portion of the age-relatedvariancein

speed.Additional mechanismsmust thereforebe identified

to accountfor much of the nesativerelationsbetweenase

and speed.

AcKNowt-EDcMENTs

This researchwas supportedby NIA grant (R37 AGO6826) to Timothy

A. Salthouse.Julie Earles was supportedby an lnstitutional Research

Training Crant (T32-AG00I 75) to the Schoolof Psychologyat The Georgia

lnstituteof Technology.

Address conespondenceto Dr. Julie L, Earles, Departmentof Psyc h o l o g y , F u r m a n U n i v e r s i t y , 3 3 0 0 P o i n s e t tH i g h w a y , G r e e n v i l l e .S C

296 | 3-0999.

REFERENCES

B i r r e n , J . E . ( 1 9 6 5 ) .A g e c h a n g e si n s p e e do f b e h a v i o r :I t s c e n t r a ln a t u r e

a n d p h y s i o l o g i c acl o r r e l a t e sl.n A . T . W e l f b r d & J . E . B i n e n ( E d s . ) ,

(pp. 19l-216\. Springlield.

Behuvior, aging, and the nervouss_t.rle,rl

l L : C h a r l e sC T h o m a s .

B i r r e n ,J . E . , W o o d s ,A . M . , & W i l l i a m s ,M . V . ( I 9 7 9 ) .S p e e do f b e h a v i o r

as an indicatorofagechangesand the integrityofthe nervoussystem.ln

F . H o i f m e i s t e&

r C . M u l l e r ( E d s . ) ,B r a i n J u t t t r i o na n d o l d a g e ( p p . l 0 44). New York: Springer-Verlag.

B o l l e r ,F . , V r t u n s k i ,P . 8 . , M a c k . J . L . , & K i m , Y . ( 1 9 7 7 ) .N e u r o p s y chologicaf correlates of hypertension.Art'hives oJ Neurologt', 34,

70 I -705 .

B o t w i n i c k ,J . , W e s t , R . , & S t o r a n d t ,M . ( 1 9 7 8 ) .P r e d i c t i n gd e a t hf r o m

. Journal of Gerontology, 33, 755-762.

behavioraftest performance

Breckler, S. J. (1990). Applicationsof covarianceslructuremodeling in

psychology:Causefor concern?Ps ,-t'hologit'al

Bulletin, 107, 260-2'73.

Dawber, T. R. (1980). The FraminghamStadr'.Cambridge,MA: Harvard

University Press.

E l i a s ,M . F . , R o b b i n s ,M . A . , S c h u l t z ,N . R . , & P i e r c e ,T . W . ( 1 9 9 0 ) .I s

blood pressurean important variable in researchon aging and neuropsychological test performance? Journal of Gerontology: Psychological

S c i e n c e s4. J . P l 2 8 - P 1 3 5

, . B . , C o b b ,J . , & W h i t e ,L . R .

E l i a s ,M . F . , W o l f , P . A . , D ' A g o s t i n o R

(1993). Untreatedblood pressurelevel is inverselyrelatedto cognitive

functioning:The Framinghamstudy. AmericanJournal of Epidemiolo91,, 138' 353-364.

F a r m e r ,M . 8 . , K i t t n e r ,S . J . , A b b o t t ,R . D . , W o l z . M . M . , W o l f , P . A . , &

White, L. R. (1990). Longitudinally measuredblood pressure,antihy-

P40

EARLESANDSALTHOUSE

Dtscusston

Both healthand speedwerefound to vary with age,but the

age-speedrelationswere only weakly mediatedby health.

This is consistent

with the resultsof Salthouse

et al. ( 1990).

who found only weak mediationby healthof age-cognition

relations.Evenwith a very basicability (i.e., the speedwith

which elementaryoperationscan be executed),therefore,

healthdoesnot accountfor a largeamountof the age-related

variancein performance.Although healthdid havea moderate effect on sensory-motorspeed,all of the effectsof selfratedhealthon perceptualspeedwere indirect and mediated

throughsensory-motorspeed.

Becausesubstantialdirect effects of age on speedwere

evidentin additionto the effectsmediatedby healthstatus,it

can be concludedthat factors other than self-ratedhealth

statusare responsiblefor much of age-relatedslowing in

relativelyhealthyadults.It is possiblethat, as Binen ( 1965;

Birren, Woods, & Williams, 1979) has suggested,agerelatedslowingis a manifestation

of primaryaging, and is

relativelyindependent

ofdisease.The relationsthatdo exist

betweenself-assessed

healthstatusand measuresof speed

could:(a) reflectweak causalinfluencesof healthon speed;

(b) be a consequence

of a common influenceof biological

statuson both setsof variables.or (c) representan effect of

basingthe ratingof one'shealthat leastpartiallyon assessmentsof one'sspeedof perfbrmance.

Obviously,additional

researchis neededto distinguishamongthesealternatives.

An important f'eatureof the cunent project was that (as

recommendedby Breckler, 1990)the model modification

procedurewas cross-validated

in an independent

sampleto

decrease

the likelihoodofcapitalizationon chance.Because

the samepatternof resultswas evidentin two moderately

large samples,the reportedrelationsappearquite robust.

The hypothesized

modelfit thedataadequately,

andtheonly

significantproblemoccurredwhen the cardiovascular

diseaseconstructwas addedto the model. This constructwas

weak in the current project becausefew subjectsreported

cardiovascularproblems, and the indicators did not load

highly on the f'actor.

There are severallimitationsconcerningthe mannerin

which healthwas evaluatedin this project.First, one can

questionthe validity of self-reportedhealth status as a

measureof objectivehealth.However, it shouldbe noted

that self-ratedhealth has been found to relate to physician

(LaRue,Bank,Jarvik,& Hetland,1979),numassessments

ber of prescriptionmedications(Salthouse,Kausler, &

Saults,1990),andlongevity(Botwinick,West, & Storandt,

1978; see page 59 in Salthouse(1991) for more relevant

citations).Thus,althoughself-ratings

providea muchcruder

evaluationof healthstatusthan do physicianassessments,

they are relatedto more objectivemeasuresof healthstatus.

Second,an attemptwas madeto recruitonly healthyvolunteers, and hence the range of health was undoubtedlyrestrictedrelativeto the generalpopulation.Thus the resultsof

the current study can only be generalizedto the relatively

healthy adult population.Nevertheless,becausesignificant

negativeage relationswere found with both the health and

speedmeasures,an opportunitydid exist for at least some

mediationalinfluence.

Althoush the results with the cardiovascularconstruct

must be consideredtentativebecauseof weak assessment

of

this construct, cardiovascularstatusmay be an important

factor in the negativerelationsbetweenageand self-reported

health status,and betweenself-reportedhealth and speed.

Previousresearchsuggestedthat cardiovasculardiseasewas

relatedto both perceptualspeed(Speith, 1964) and higher

cognitivefunctioning(Hultschet al., 1993).In the current

study, almost all of the effects of health on sensory-motor

speedwere mediatedby cardiovasculardisease,suggesting

that cardiovasculardiseasemay be the aspectof healththat

contributesto the negativerelationsbetweenageand speed.

This interpretation,however,needsto be investigatedmore

directly with more sensitiveandobjectivemeasuresof health

and cardiovascularstatus before it can be acceptedwith

confidence.

In summary,self-ratedhealthand speedwere both negatively relatedto increasedage. However, healthonly partially mediatedthe age-relatedvariationin speed,and much of

the relationthat did exist betweenhealthand speedappears

to have been mediatedby cardiovascularstatus.The major

conclusionfrom theseanalysesis that,within this relatively

healthysampleof adults,healthstatuswas associated

with

only a relativelysmallportionof the age-related

variancein

speed.Additional mechanismsmust thereforebe identified

to accountfor much of the neeativerelationsbetweenage

and speed.

AcKNowLEDCMt

NTS

This researchwas supportedby NIA grant (R37 AGO6826) b Timothy

A. Salthouse.Julie Earles was supportedby an lnstitutional Research

Training Grant (T32-AG00| 75) to the Schoolof Psychologyat The Georgia

Instituteof Technology.

Address correspondenceto Dr. Julie L. Earles, Departmentof Psyc h o l o g y , F u r m a n U n i v e r s i t y , 3 3 0 0 P o i n s e t tH i g h w a y , G r e e n v i l l e ,S C

296 | 3-0999.

RupsneNces

B i r r e n ,J . E . ( 1 9 6 5 ) .A g e c h a n g e si n s p e e do f b e h a v i o r :I t s c e n t r a ln a t u r e

a n d p h y s i o l o g i c acl o r r e l a t e sl.n A . T . W e l f b r d & J . E . B i n e n ( E d s . ) .

(pp. 19l-216). Springlield.

Behut'ior. uging, und the nervous.r_r.r/er?

l L : C h a r l e sC T h o m a s .

, . V . ( I 9 7 9 ) .S p e e do f b e h a v i o r

B i n e n ,J . 8 . , W o o d s ,A . M . , & W i l l i a m s M

as an indicatorofagechangesand the integrityofthe nervoussystem.ln

F . H o f T m e i s t e&r C . M u l l e r ( E d s . ) ,B r a i n . l u n c t i on n d o l d a g e ( p p . I 0 44). New York: Springer-Verlag.

B o l l e r , F . , V r t u n s k i ,P . 8 . , M a c k , J . L . , & K i m . Y . ( 1 9 7 7 ) .N e u r o p s y chological correlates of hypertension.Art'hives of Neurologt', 34,

70l -705.

B o t w i n i c k ,J . . W e s t . R . , & S t o r a n d t ,M . ( 1 9 7 8 ) . P r e d i c t i n gd e a t hf r o m

. J ournaI of G erontolo 91,,33, 755-i 62.

behavioraltest performance

B r e c k l e r ,S . J . ( 1 9 9 0 ) .A p p l i c a t i o n so f c o v a r i a n c es t r u c t u r em o d e l i n gi n

psychology:Causefor concern'!P s,-cltologi<

ol Bulletin, I 07 , 260-273 .

Dawber, T. R. (1980). The FraminghamSrud_r'.

Cambridge.MA: Harvard

University Press.

E l i a s ,M . F . , R o b b i n s ,M . A . , S c h u l t z ,N . R . , & P i e r c e , T . W . ( 1 9 9 0 ) .I s

blood pressurean important variable in researchon aging and neuropsychological test performance'! Journal of Gerontology: Psychological

S c i e n c e s4, 5 , P l 2 8 - P l 3 5 .

E l i a s ,M . F . , W o l f , P . A . , D ' A g o s t i n o R

, . 8 . , C o b b ,J . , & W h i t e ,L . R .

(1993). Untreatedblood pressurelevel is inverselyrelatedto cognitive

functioning:The Framinghamstudy.American Journal of Epidemiology, 138,353-364.

F a r m e r ,M . 8 . , K i l t n e r ,S . J . , A b b o n , R . D . , W o l z , M . M . , W o l f , P . A . , &

White, L. R. (1990). Longitudinallymeasuredblood pressure,antihy-

AGE, HEALTH, ANDSPEED

pertensive medication use, and cognitive performance: The

Framingham study. Journal oJ Clinical Epidemiology, 43, 475-480.

F i e l d ,D . , S c h a i e K

, . W . , & L e i n o ,E . V . ( 1 9 8 8 ) .C o n t i n u i t yi n i n t e l l e c t u a l

functioning: The role of self-reportedhealth. Psychology and Aging,4,

385-392.

F r a n c e s c h iM

, . , T a n c r e d i ,O . , S m i m e , S . , M e r c i n e l l i ,A . , & C a n a l , N .

(1982). Cognitive processes in hypertension. Hypertension, 4,

226-229.

Hertzog, C. ( 1989).Influencesof cognitive slowing on age differencesin

intelligence.D evelopmental PsychoIo gy',25, 636-65 | .

H e r t z o g ,C . K . , S c h a i e ,K . W . , & G r i b b o n , K . ( 1 9 7 8 ) .C a r d i o v a s c u l a r

diseaseand changesin intellectualfunction from middle to old age.

Journal of Cerontologr, 33 , 872-883.

H u l t s c h ,D . F . , H a m m e r ,M . , & S m a l l , B . J . ( 1 9 9 3 ) .A g e d i f f e r e n c e isn

cognitiveperformancein laterlife: Relationshipsto self-reportedhealth

and activity life style. Journal oJ Gerontology: Psychological Sciences,

4 8 .P l - P l l .

Krause, N. (1990). Perceivedhealth problems, formal/informal support,

and life satisfactionamong older adults. Journal ofGerontologl': Sot'ial

S c i e n c e s4. 5 . S 1 9 3 - 5 2 0 5 .

L a R u e .A . . B a n k . L . , J a r v i k ,L . , & H e t l a n d ,M . ( 1 9 7 9 ) .H e a l t hi n o l d a g e :

Journul oJGeronHow do physicians'ratingsand self'-ratings

compare"!

tologt', 34, 687-69 I .

Light, K. C. (1978). Effects of mild cardiovascularand cerebrovascular

disorders on serial reaction time performance. Experimental Aging

Research,4,3-22.

L i n d e n b e r g e rU, . , M a y r , U . , & K I i e g l , R . ( | 9 9 3 ) .S p e e da n di n t e l l i g e n c ien

o l d a g e .P q ' < & o / o g u

y n d A g i n g ,U , 2 0 ' l - 2 2 0 .

M i t t e l m a r k .M . B . . P s a t y ,B . M . , R a u t a h a r j uP, . M . , F r i e d ,L . P . , B o r h a n i ,

N . O . , T r a c y , R . P . , G a r d i n ,J . M . , & O ' L e a r y , D . H . ( 1 9 9 3 ) .

Prevalenceof cardiovasculardiseasesamongolder adults:The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ameritun Jutrrutl oJ Epidemiologt', l-17,

3l l-317.

Perlmutter.M. . & Nyquist. L. ( I 990). Relationshipsbetweenself-reported

physical and mental health and intelligenceperformanceacrossadulthood. Journal o.f Gentntology': Psl't'hologit'al Scien<'es, 45,

Pt45-P155.

R a y k o v ,T . , T o m e r ,A . , & N e s s e l r o a d eJ ,. R . ( 1 9 9 1 ) .R e p o r t i n gs t r u c t u r a l

equation modeling results in Psychologyand Aging: Some proposed

guidelines.Psl t'hoIo g1'and A gi ng, 6, 499- 5O3.

P4l

Salthouse,T. A. (1991). Theoretical perspectiveson cognirive uging.

Hillsdale, NJ: LawrenceErlbaum Associates.

Salthouse, T. A. ( 1992). Mechanisms of age cognition relations in adultftood. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Salthouse,T. A. (1993a). Speedand knowledgeas determinanlsof adult

age differences in verbal tasks. Joanral oJ'Gerontology: Psychological

Sciences,48,P29-P36.

Salthouse,T. A. (1993b). Speed mediation of adult age differencesin

cognition.D eveI opmental P sy'

t'hoI o 91,29, 722-7 38.

Salthouse,T. A. ( 1994).The natureof the influenceof speedon adult age

differencesin cognition. Developmental P s1,c

holog,-,30, 240-259.

Salthouse,T. A. (in press).Aging associations:

lnfluenceof age and speed

on associative learning. J ournal oJ'Experimental P sl,chologl,: Learning, Memon', and Cognitton.

S a l t h o u s eT, . A . , K a u s l e r ,D . H . , & S a u l t sJ, . S . ( 1 9 9 0 ) .A g e , s e l f - a s s e s s c d

health status, and cognition. Journal ol Gerontologl,:Psl'chological

St'iences.45. Pl 56-Pl 60

Schaie,K. W. (1989). Perceptualspeedin adulthood:Cross-sectional

and

g,- und A gi ng, 4, 443- 453.

longitudinalstudies.Ps_r'cholo

S c h u l t z ,N . R . , E l i a s , M . F . , R o b b i n s .M . A . , S t r e e t e n D

, . H. P., &

Blakeman,N. ( 1986).A longitudinalcomparisonof hypertensivesand

normotensiveson the Wechsler Adult IntelligenceScale: Initial tindi n g s .J o u r n a lo l G e r o n n l o g l ' , 4 l , 1 6 9 - l 7 5 .

S h a p i r o ,A . P . , M i l l e r . R . E . , K i n g , 8 . , G i n c h e r e a uE, . H . , & F i t z g i b b o n ,

K. (1982). Behavioralconsequences

of mild hypertension.H1-perten.siorr.4. 355-360.

Speith, W. (1964). Cardiovascularhealth status.age, and psychological

performance.J ournal ol G erontologt, I 9, 277-284.

Speith, W. (1965). Slowness of task perlbrmance and cardiovascular

diseases.ln A. T. Weltbrd & J. E. Binen (Eds.), Behavior,uging, and

(pp. 366-400). Springfield.IL: CharlesC Thomas.

the nerwus s.r'.rrern

v a n S w i e t e n ,J . C . , G e y s k e s ,G . G . , D e r i x , M . M . A . , P e e c k ,B . M . ,

R a m o s ,L . M . P . , v a n L a t u m , J . C . , & v a n G i j n , J . ( 1 9 9 1 ) .A n n a l so l

N eurolog1',30, 825-830.

W i l k i e , F . L . , E i s d o r l ' e rC, . . & N o w l i n , J . B . ( 1 9 7 6 ) .M e m o r y a n d b l o o d

pressurein the aged.E"rltarimentalAging Research,2, 3-16.

ReceivedJanuttn 1l, 1994

Ac<eptedMa-t 25, 1994