Timothy A. Salthouse

advertisement

taL:()dicmemory.

l.'rrtions: SPatial

fn1('ntia:MethodReoiews,

t:.;':,.lism

lr.rl Corporation.

r,,ration.

TimothyA. Salthouse

TheBroaderContextof Craik's

Hypothesis

Self-lnitiatedProcessing

I am delighted to participate in the conference and contribute to the resulting volume

honoring Gus Craik, who is widely recognized as a leading experimental psychologist

investigatingboth basic processesin memory and the effectsof increasedage on memory.

I have long been an admirer of Craik's creative experiments and intuitively appealing

theoretical interpretations, and like many others I have enjoyed and benefited from collaborations with him, in my case as a coeditor of the first and second editions of the

Handbookof Aging and Cognition(Craik & Salthouse, 1992, 2000). Becausehe is as nice

interpersonally as he is esteemedscientifically,I can think of no person more deserving of

this t)?e of recognition.

This event is intended to commemorateGus's retirement from the University of Toronto,

and it is often appropriate when such a distinguished individual completesan important

phase of his career to attempt to classifyand evaluatehis contributions. I will leave it to

others to evaluatehis contributions, and instead I will attempt a preliminary classification

of where he stands with respect to major schools or systems within psychology. Although

Craik is indeed an outstanding experimental psychologist,I suggestthat he may have at

least as much in common with Charles Spearman,one of the pioneers of psychometricor

individual difference psychology, as with Wilhelm Wundt, who is often considered the

founding father of experimental psychologr.

I will explain this perhaps surprising claim by first describing two broad approaches

that have been used to investigateand explain adult age differencesin memory and other

aspectsof cognitive functioning. One approach can be characterizedas largely analytical

and specific, in that it is designed to seek interpretations based on Processeshypothesized to be involved in the task under investigation. The second approach is more general, in that it tends to emphasize influences that have an impact at a level broader than

that of individual variables.

Most researchconcernedwith adult age differencesin memory has focused on variants

of the specificapproach becausethe goal has been to decomposeor fractionatethe task to

identify constituent processes,and then determine the magnitude of the age-relatedeffects on each process. This micro approach has frequently been successful in identiS'ing

processes with differential sensitivity to advancing age. For example, age-related effects

278

Perspectives

on Human Memory and CognitiveAging

are typically greater on controlled processesthan on automatic processes,and on processesassociatedwith explicit memory than on processesassociatedwith implicit memory.

The micro perspectiveis representedin this volume by the contributions of Jacoby,Marsh,

and Dolan (chapter19); McDowd (chapter11);Naveh-Benjamin(chapter15); and Koustaal

and Schacter(chapter 30).

The alternative macroapproach tends to emphasizeage-relatedeffects that operate on

severaldifferent tyPes of variables.These broader influences may be related to effectson

a critical processor theoretical construct, such as encoding or goal maintenance, or they

may be linked to an attribute such as working memory capacity,effectivenessof deploying or inhibiting attention, or speed of processing.The common feature of these more

generalperspectivesis that they postulatethat at least some of the age-relatedeffectson a

given variable are not specific to that variable, but instead are shared with several different kinds of variables.

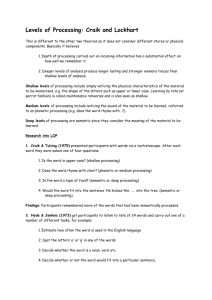

Figare 22.1 contains a schematic illustration of the micro and macro perspectivesin

cognitive aging. The top panel portrays the decomposition of a variable into a number (in

this case,three) of hypothesized processesor components, and the bottom panel represents age-related effects operating on several different types of cognitive variables.

Although much of Craik's researchhas attempted to fractionatememory tasks to isolate

the age-relatedeffects to specific processes,he has also been sympathetic to, and sometimes even an ardent advocateof, the macro or general perspectivebecausehe has hy-

Micro

^,-4

r,

*\-T",2-

l P a l l P B ll P c l

>4

M i q E M

Decomposethe task into constituentprocesses,and examinethe

age sensitivityof each component

Macro

Examineage-relatedinfluencesthat simultaneously

operate

on several differentvariables

FIGURE22.1. Schematicillustrationof micro (decompositional)and macro (integrative)

approachesto investigating

adult age differencesin cognition.

I

pothesizedthat in addition to task-spe

on some form of processingresourcet

different types of memory tasks. Crai

(e.9.,1927\becauseboth he and Spt

variables representing different cognr

tion of general and specific influencel

have used the term mental energVto re

eral influences. However, they differ i

people and acrossvariables.

As most psychologists know, Spean

general factor manifested in different r

ably related to the amount of mental e

of g is self-initiated processing (some

required in different amounts acrossI

presumably related to the amount of r

1986) portrayed his self-initiated prcre

rows representeddifferent memorv t:

of self-initiated processingincreased

differences.A major goal of the hrlxr{

tude of age differencesin memon' r'ar

ferences,with progressivelylarger drff

and finally the largestagedifferencesfr

processinghypothesisis the notion of r

along the self-initiated processingdrm

ing amounts of environmental suppro

etc., that serve to reduce the nmount r

task, and hence also to decreasethe n

Craik's self-initiatedprocessinghrR

aging phenomena might be explaina

understood.The concept of self-initra

ber of other proposals such as control

cessing, and reflective processing. ln

hypothesizedto differ in the amount ol

and on average,the eftectivenessof c

decreasewith increasingage. Each of t

difficulties of how to operationalizethr

measuresof the construct to avoid pr

construct is inferred from the same Fu

Craik and his colleagues have ret-t6

them in a number of ingenious erp'e

found that when researchparticipants

a memory task not only were older ad

ment to perform the two tasks simulta

larger for a free recall memort' tasl t

ivere replicated and extended in a :t-n

Beniamin (1998),in which the secon&

cued recall to recognition. The discove

of memory tasks can be predicted fr'

presumed to reflect self-initiated pro

Craik's self-initiated processinghrprt:

Craik'sSelf-lnitiated

ProcessingHypothesis

.r:lJ on Prol r t r :n t e m o n ' .

r c , , l . r\ .1 a r s h .

a:'J Koustaal

li

"''.t'rc-lt€

OII

t., ( llects on

a:'. ! ')r the\

: Jcplor'. .._r,(,nt()fr,

ti r iir'r ts Oft .t

rr '. . '.t I eliiterrI -'.-r ! t lVC\

ln

. ' )" . ; : r ' r b t r I l n

:'.r:'r; rcPrel:.1 l' r .

i.\.',,

.

.l

tr(rl.ttc

-J

.1rP11'

:. :', ir.t: ht -

279

pothesizedthat in addition to task-specificprocesses,there are also age-relatedinfluences

on some form of processingresourcethat is needed for the effectiveperformance of many

different types of memory tasks. Craik can therefore be considered similar to Spearman

(e.9., 1927) becauseboth he and Spearman have argued that individual differences in

variables representing different cognitive tasks or abilities are attributable to a combination of general and specific influences. Spearman and Craik are also similar in that both

have used the term mental energyto refer to the basis of individual differences in the general influences. However, they differ in their proposals about what it is that varies across

people and acrossvariables.

As most psychologistsknow, Spearman proposed the concept of g, which refers to the

generalfactor manifestedin different degreesacrossmost variablesand which is presumably related to the amount of mental energy availableto an individual. Craik's equivalent

of g is self-initiated processing (sometimesreferred to as SIP), which he hypothesized is

required in different amounts acrossdifferent types of memory tasks, and which is also

presumably related to the amount of mental energy an individual possesses.Craik (e.g.,

1986)portrayed his self-initiatedprocessinghypothesisin the form of a table in which the

rows representeddifferent memory tasks and the columns indicated that as the amount

of self-initiated processing increased, so did the expected magnitude of the age-related

differences.A major goal of the hypothesiswas to account for an ordering of the magnitude of age differencesin memory variables,ranging from priming with the smallestdifferences,with progressivelylarger differencesfor relearning, recognition, and cued recall,

and finally the largestage differencesfor free recall. Another aspectof Craik's self-initiated

processinghypothesisis the notion of environmental support becausesuccessivepositions

along the self-initiated processingdimension were postulated to be associatedwith varying amounts of environmental support. This support existed in the form of cues, context,

etc., that serve to reduce the amount of self-initiated processingrequired to perform the

task, and hence also to decreasethe magnitude of the resulting age-relateddifferences.

Craik's self-initiatedprocessinghypothesisis intriguing becauseit implies that memory

aging phenomena might be explained once the nature of self-initiated processing was

understood.The concept of self-initiated processingsharessome similarities with a number of other proposals such as controlled processing,effortful processing,deliberate processing, and reflective processing. In every case, memory or other cognitive tasks are

hypothesizedto differ in the amount of this processingneededfor successfulperformance,

and on average/the eftectivenessof carrying out this type of processingis postulated to

decreasewith increasing age. Each of these proposalshas plausibility, but they all face the

difficulties of how to operationalizethe relevant construct and how to obtain independent

measuresof the construct to avoid problems of circularity in which the existence of the

construct is inferred from the same pattern of results that it is supposed to explain.

Craik and his colleagueshave recognized these issuesand have attempted to deal with

them in a number of ingenious experiments. For example, Craik and McDowd (1987)

found that when researchparticipants were asked to perform a reaction time task during

a memory task not only were older adults slowed more than young adults by the requirement to perform the two tasks simultaneously,but the reaction times in both groups were

larger for a free recall memory task than for a recognition memory task. These results

were replicated and extended in a seriesof experiments by Anderson, Craik, and NavehBenjamin (1998),in which the secondaryreaction time costsdecreasedfrom free recall to

cued recall to recognition. The discoverythat the magnitude of age differenceson a series

of memory tasks can be predicted from a variable (i.e., secondary task reaction time)

presumed to reflect self-initiated processing demands provides impressive support for

Craik's self-initiated processinghypothesis.

280

I

on Human Memory and CognitiveAging

Perspectives

of adult

In the remainder of this article I will describe a different approach to the study

different

quite

a

with

I

will

start

variables.

cognitive

age differences in memory and other

up with an

qirestion and will rely on a different methodological approach, but I will end

hypothesis'

self-initiated

by

Craik's

implied

that

to

Processing

similar

function

"rr.,piricat

selfIn order to highlight the correspondence between my apProach and the Craikian

graph

the

into

hypothesis

Craik's

transform

will

first

initiated pro.Jrsi.,g hypothesis, I

related to

portrayed' in ftg"re ZZ.iin which self-initiated processing and age are positively

along the

one another, and different memory variables are located at different positions

hypothesis,

Craik's

of

principle

key

the

function. Note that this representalion embodies

pronamely, that there is a sysiematic relationship between the amount of self-initiated

it is easier

cessing required and the magnitude of the age differences on the variable, but

to illustrate the similarity to my approach with this form of lePresentation.

two types

A fundamental assumption of my perspective is that all variables have at least

variable and

particular

to

a

specific

are

that

iniluences

unique

influences:

of age-related

I also

shared influences that are common to many different types of cognitive variables'

with

age

relation

of

their

magnitude

total

assume that not only do variables differ in the

varisome

that

such

influences,

of

types

two

of

the

but also in the relative contributions

have largelv

ables primarily have unique age-related influences, whereas other variables

twes of influences, but it is simplest

what can be termed the shared infl

Hambrik, & McGuthry, 1998).The tu

the variance that all variables have u

statisticalproceduressuch as princip

equation modeling. The next step in t

mon variancebeforeexaminingager

on individual variables in this h'pe of

variables have in common correspor

effects that are mediated through the

lvtical method is not necessarilvinfo

different cognitive variables, but it d

encesto be partitioned into unique rd

Application of the method can be ill

and Rhee (1996),which involved 259

variableswere examined in this studv

shared influences.

of the two

Several analytical methods can be used to estimate the relative contributions

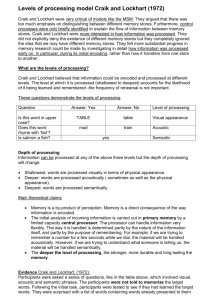

TABTE

22.1. Proportionsof total, C|.

Fristoe,and Rhee(1996)

Salthouse,

:

FreeRecall

Self

lnitiated

Processing

Magnitude

of

Age

Difference

CuedRecall

Recognition

Relearning

Priming

ot

'6

o

o

o

o

.

'

Free Recall ,j

j

Cued Recall

n

E

o

o

Recognition

'=

Ic)

a

Relearning

,-'

i

,

.

'

Priming ...

AbsoluteAge Correlation

processinghypothesis'

reoresentationof Craik'sself-initiated

FICURE22.2. Alternative

Variable

Total

RVLT2

RVLT6

Recog

P,\1

PA2

WCST

TrailsA

TrailsB

Shipley

BlkDes

ObjAssm

DigSym

LetCom

PatCom

.220

.199

.108

.261

.123

.167

.256

.348

.199

.219

.170

.429

Median

.220

-z1-t

.436

,!ote: RVLT2refers to the number oi

LearningTest;RVLT6to the numbero

the ReyVerbal LearningTest;Recoqt

PA1 and PA2 to the nu

LearningTest;

WCSTto the nur

of oairedassociates;

SortingTest,TrailsAand TrailsBto the tr

of the TrailMakingTest;Shipleyto the

Instituteof LivingScale;BlkDesto the

object assemblyscore from the \\ \

from the WAIS-R;LetComto the num

and PatComto the number of itemsc

articlefor detailson thesetests.

C r a i k ' s S e l f - l n i t i a t e d P r o c e s s i n g H y p o t h e s 2i s8 1

d:::.:.-:

t \\::: --:F\:.1-.h< .:.,:':

:eiJ:r -: :

l L ' : . : . -t

r \ : : ' 1- . ai(.::-:

ll

il\

-

-jt .

iar.. -,-:

le. .: -.

i't

types of influences, but it is simplest to illustrate how the estimates can be derived with

what can be termed the shared influences method (see Salthouse, 1,998;Salthouse,

Hambrik, & McGuthry, 1998).The first step in this procedure is to obtain an estimate of

the variance that all variables have in common. This can be achieved with a variety of

statisticalproceduressuch as principal components analysis,factor analysis,or structural

equation modeling. The next step in the procedure is to control an estimate of this common variance before examining age-related effects on individual variables. Effects of age

on individual variables in this type of analysis that are evident after controlling what the

variables have in common correspond to direct or unique age-relatedeffects, whereas

effects that are mediated through the common factor represent shared effects. This analytical method is not necessarily informative about the nature of what is shared among

different cognitive variables, but it does provide a means of allowing age-related influencesto be partitioned into unique (direct) and shared (indirect) aspects.

Application of the method can be illustrated with data from a study by Salthouse, Fristoe,

and Rhee (1996),which involved 259 adults between 19 and,94years ofage. A total of 14

variableswere examined in this study, including three measuresof episodicmemory from

. , 1 -i r . .

tl::1

:.\

TABLE22.1.Proportionsoftotal,shared,anduniqueage-relatedvariancefromstudyby

Salthouse, Fristoe, and Rhee (1996).

Age-relatedvariance (r2)

Shared

Unique

.436

.217

.196

.096

.257

.114

.166

.256

.344

.184

.216

.167

.418

.241

.395

.003

.003

.o12

.004

.009

.001

.000

.004

.015

.003

.003

.011

.002

.o41

.220

.220

.004

Variable

Total

RVLT2

RVLT6

Recog

PAl

PA2

WCST

TrailsA

TrailsB

Shipley

BlkDes

ObjAssm

DigSym

LetCom

PatCom

.220

.199

.108

.261

.123

.167

.256

.348

.199

.219

.170

.429

Vedian

.z+-)

lotei RVLT2refersto the number of words recalledin the second trial of the ReyVerbal

LearningTest;RVLT6to the number of words recalledin the sixth(postinterference)

trial of

the ReyVerbalLearningTest;Recogto the score in the recognitiontest of the ReyVerbal

LearningTest;PA1 and PA2to the number of responsetermscorrectlyrecalledin two lists

of pairedassociates;

WCSTto the number of categoriescompletedin the WisconsinCard

SoitingTest,TrailsAand TrailsB

to the time neededto completeversionsA and B, respectively,

of the TrailMakingTest;Shipleyto the abstraction(seriescompletion)scorefrom the Shipley

Instituteof LivingScale;BlkDesto the block designscorefrom the WAIS-R;ObjAssmto the

object assemblyscore from the WAIS-R;DigSym to the digit symbol substitutionscore

irom the WAIS-R;LetComto the number of itemscompletedin the lettercomparisontest;

,ind PatComto the number of itemscompletedin the patterncomparisontest.Seeoriginal

,rrticlefor detailson thesetests.

282

Perspectives

on Human Memory and CognitiveAging

Crark

the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test: free recall on the second trial, free recall after an

interference list, and recogrrition. The estimate of the common variance in the shared

influence analysis was based on the (unrotated) first principal component obtained faom

a principal components analysis on the 14 variables. Table 22.1.contains the total agerelated variance and the estimates of shared and unique age-related variance for each

variable. Notice that the median proportion of age-related variance across the L4 variables

was .220, which corresponds to an age correlation of -.47. However, the median proportion of unique age-related variance was only .004, which is less than 2"/"of the total agerelated variance and corresponds to an (absolute) age correlation of .06. The results summarized in Table 22|1. are typical of many analyses of this type because it has frequently

been found that only a small proportion of the total age-related effects on a given variable

are unique to that variable and independent of the age-related effects on other variables

(e.g.,Salthouse,'1.998,2001;

Salthouse,et al., 1998).

An interesting implication of the finding that a large proportion of the age-related effects on one variable is shared with the age-related effects on other variables is that there

should be a positive relation between the magnitude of the age relation on a variable and

the degree to which that variable is related to other variables. That is, if large proportions

of the age-related effects on different cognitive variables are shared, then the magnitude

of the age relation on a variable should closely correspond to the degree to which that

variable is related to, or has aspects in common with, other variables. Stated somewhat

differently, if a substantial amount of the age-related effects on a particular variable is

mediated through a factor representing what is common to all variables, then the size of

the age relation for that variable should be proportional to the strength of the relation

between the target variable and the common factor. This reasoning leads to the prediction

that there should be a strong positive relation between the absolute magnitude of the age

relation on the variable and the degree to which that variable is related to other variables.

I refer to these predicted functions as AR functions becausethe axesrepresentrelations of

the variable to age (A) and to relatedness (R).

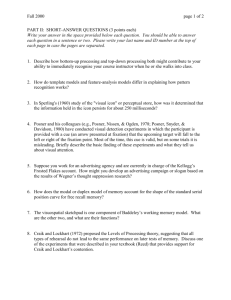

The prediction of positive AR functions across different combinations of cognitive variables has recently received a considerable amount of empirical support. For example, Figure 22.3 illustrates the AR function with data from 14 variables in the Salthouse et al.

(1996) study (see Table 22|1. for a descript

corresponds to a single variable, with its al

and its loading on the first principal coml

mon to all variables, along the ordinate. I

tween the two sets of values, as the Pean

correlation was .81.

A similar pattern was evident in a later s

(1997), involving an independent sample r

variables. The data from this study are illus

the Pearson r was .83 and Spearman's ranJ

aspect of this latter study was that it inchx

cessing in a stem completion memorv task

tion procedure. Although the measure of r

cated close to the center of the AR functio

variables, the measure of automatic proce:

the function, indicating that the variable h

finding is therefore consistent with the ass

a qualitatively different type of processing

age-related effects are minimal to nonexis

ing. It is important to note that the autcr

respectablelevel of reliability (i.e., .82), ar

variables cannot be attributed to a low letr

able to be shared with other variables.

Similar patterns of positive AR function

tory, as the median rank-order correlation

phenomenon is not an artifact of differenu

lations were nearly the same magnitude

Salthouse,2001).Moreover, the phenomm

because it is evident in analyses of data 6

large-scale studies by Park and her collab

Saltr(r

Salthouse.Fristoe& Rhee ( 1996)

0.9

0.9

E

()

5 o.a

E

o

o

6

r=.84

rho = .81

0.7

E

o

6

aPAl

ob^ssma-./

'tr

(L

a

a

!

wcsT

U c

ne

o.s

3 oo

a

RVLT2

(L

o.a

5

oz

o

Shipley

a TrailsA

BlkD€sa a

RVLT6a

'o

.E 0.6

c

E

o

DigSym

1mil3ts

o

O

c

t 0.4

o

o

n

- -a

0.2

- '

^^

s.s

E

--o.2

0,

t

J

0.3

0.2

0.3

0.5

0.6

0.4

AbsoluteAge Correlation

0.7

0.8

FIGURE 22.3. Variables plotted in terms of their absolute correlation with age (horizontal

a x i s ) a n d t h e i r d e g r e e o f r e l a t e d n e s st o o t h e r v a r i a b l e s ( v e r t i c a l a x i s ) . D a t a f r o m S a l t h o u s e ,

Fristoe,and Rhee (1996).

0.0

0.1

0.2

0!

A!.dl

FIGURE22.4. Yariablesolottedin termsoi

axis)andtheirdegreeof relatedness

to othr

Toth,Hancock,andWoodard(1997).

ProcessingHypothesis

Craik'sSelf-lnitiated

free recall after an

ancr' in the shared

rt'nt obtained from

tarns the total ageI r.rriance for each

rl\: the 14 variables

lhc median proporI r, of the total ageh The results sum-scit has frequently

\)n .l Fven variable

t r)n other variables

f the age-relatedefis that there

rrr.rL'les

In ()n a variable and

rf l.rrgeProportlons

thcn the magnitude

egrr'r' to which that

: 5t.rted somewhat

artrcularvariable is

,le. then the sizeof

nsth of the relation

rd. to the prediction

u{nitude of the age

'l t,, Lrthervariables.

efr('\cnt relationsol

)n- ,rf cognitive vari

r: Ior example,Fig'

thr' Salthouseet al.

283

(1996) study (see Table 22.L for a description of the variables). Each point in this figure

corresponds to a single variable, with its absolute correlation with age along the abscissa

and its loading on the first principal component, representing what is statistically common to all variables, along the ordinate. Note that there is a clear positive relation between the two sets of values, as the Pearson / was .84 and Spearman's rank-order rho

correlation was .81.

A similar pattern was evident in a later study by Salthouse, Toth, Hancock, & Woodard

(1997), involving an independent sample of participants and a different combination of

variables. The data from this study are illustrated in Figure 22.4, where it can be seen that

the Pearson r was .83 and Spearman's rank-order rfto correlation was .93. An interesting

aspect of this latter study was that it included measures of automatic and controlled processing in a stem completion memory task derived from Jacoby's (1991) process-dissociation procedure. Although the measure of controlled processing (i.e., Stem-Cont) was located close to the center of the AR function and thus can be considered similar to other

variables, the measure of automatic processing (i.e., Stem-Auto) was a clear outlier from

the function, indicating that the variable had little or no relation to other variables. This

finding is therefore consistent with the assumption that automatic processing represents

a qualitatively different type of processing than that involved in many variables, and that

age-related effects are minimal to nonexistent in the effectiveness of automatic processing. It is important to note that the automatic processing variable in this study had a

respectable level of reliability (i.e., .82), and thus its lack of relation to age and to other

variables cannot be attributed to a low level of systematic variance (i.e., reliability) available to be shared with other variables.

Similar patterns of positive AR functions are evident in other studies from my laboratory, as the median rank-order correlation across 30 different data sets was .80, and the

phenomenon is not an artifact of differential reliability of the variables because the correlations were nearly the same magnitude after partialling estimates of reliability (see

Salthouse,2001).Moreover, the phenomenon is not restricted to data from my laboratory

because it is evident in analyses of data from other investigators. Data from two recent

large-scale studies by Park and her collaborators can be used to illustrate this point. A

Salthouse,Toth,et al. (1997)

0.9

-t

II

o

congrm oo!

;;3i,

E o t

,""]'ji;ff:i

S/Dr'

u./

E oe

9 o.s

6

o+

3

c

E 03

CVLT2

LetFlucncy

'

c"tFrr"n"y

'

stcm€onta

/'/

JOLO I

^!

R€cog

T6

!o n

- ',

O

c

v^ .^u

E

--o.2

0,

t

0.0

| ,\ "' rge (horizontai

[ ) . , ' . ,; r o m S a l t h o u s e

0.1

0.5

0.6

0.3

0.4

0.2

AbsoluteAge Correlation

0.7

0.8

tICURE 22.4. Yariables plotted in terms of their absolute correlation with age (horizontal

a x i s ) a n d t h e i r d e g r e e o f r e l a t e d n e s st o o t h e r v a r i a b l e s ( v e r t i c a l a x i s ) . D a t a f r o m S a l t h o u s e ,

Toth. Hancock, and Woodard (997).

284

Perspectives

on Human Memory and CognitiveAging

study publishe d in l,gg6 (Park et a1.,1996) contained data on ll variables from 30l adults

and yielded a Pearson r of .54 and a Spearman rank-order rfto correlation of .52. A study

reported in 1998 (Park, Davidson, Lantenschlager, smith, & smith, 1998) contained data

on 13 variablesfrom 345 adults, and yielded a Pearsonr of .88, and a SPearmanrho of .91'.

It should be apparent that these empirical AR functions closely resemble the relations

predicted by Craik's self-initiated processing hypothesis, as portrayed in Fig,rre 22.2. ln

both cases the horizontal axis represents the absolute magnitude of the relation of the

variable to age. The vertical axes in the two types of functions differ, because with the

hypothetical self-initiated processing functions, the axis corresponds to the amount of

self-initiated processing, and with the empirical AR functions the axis corresponds to

how closely related the variable is to other variables. However, the two situations may be

similar in that in each case the vertical dimension can be interpreted as representing the

degree of reliance on aspects of processing common to many different types of cognitive

variables. That is, the vertical axis in both functions may reflect the need to develop and

executea sequenceof processingoperationsthat require the control or allocation of attention. The hypothetical construct of self-initiated processingrepresentsthis capability directly, whereas the empirically determined relatedness index may represent it indirectly if

it is assumed that variables are related to one another to the extent that they rely on

controlled or deliberate processing.

The discovery of positive AR functions can therefore be interpreted as empirical evidence consistentwith Craik's self-initiatedprocessinghypothesis.As Craik has predicted,

the age differences are larger when there is greater reliance on something necessary for

effective performance on different memory tasks. However, it should also be noted that

the results I have described suggest that Craik's self-initiated processing hypothesis represents only a limited portion of a broader phenomenon. That is, positive AR relations are

not restricted to memory variables, and in fact, memory variables tend to be located toward the lower left region of AR functions. Across a number of analyses of this type,

involving a mixture of different kinds of cognitive variables, the upper right region of the

function is usually occupied by variables derived from reasoning tasks and perceptual

speed tasks (seeSalthouse,2001). This finding also seemsconsistentwith the controlled

processing interpretation of AR functions because reasoning tasks can be assumed to

require controlled processingto assemblea novel sequenceof processesto solve a prob'

lem, and perceptual speed tasks require controlled or effortful processingto ensure efficient execution of a simple sequenceof processingoPerations.

In conclusion, despite the dominance of the micro or task-orientedperspectivein contemporary cognitive aging research, there is considerable evidence that at least some agerelated effects on memory and other cognitive variables are shared and are not completelv

specificto a particular task. Explanations are therefore needed to account for both shared

(or general) and unique (or specific) age-related effects in cognitive aging. The discoverv

of strong positive relations between the magnitude of the age relation on a variable and

the degree to which the variable sharesvariance with other variables (i.e., AR functions)

may provide a valuable window into understanding the basis for shared age-related influences. Furthermore, one promising candidate that might account for these general effects

is Craik's notion of self-initiated processing becausethe dimension underlying the AR

functions may correspond to the amount of controlled or self-initiated processing required

by a task.

I

References

Anderson, N. D., Craik, F. I. M., & Narcr

and retrieval in younger and older

and Aging,13, 405-423.

Craik, F. I. M. (1986). A functional accq

(Eds.), Human memory nnd cognihe

Craik, F. I. M., & McDowd, J. M. (19En

mental Psychology:Learning Memor

Craik, F. I. M., & Salthouse, T. A. (Eds.) |

Craik, F. I. M., & Salthouse,T. A. (2m

Erlbaum.

Jacoby,L. L. (1991). A process dissociatir

memory. Journal of Memory and l^o

Park, D. C., Davidson, N., Lautensch.lag

oisuo-spatialand uerbalzoorkingmcn,

at the 1998 Cognitive Aging Confer

Park, D. C., Smith, A. D., Lautenschla

(1996). Mediators of long-term met

11,621-637.

Salthouse,T. A. (1998).Independence c

span. D eaelopmentalPsychology,31

Salthouse,T. A. (2001). Structural mod

tunctioning. Intelligence,29, 93-'tl')

Salthouse,T. A., Fristoe,N., & Rhee, S I

chological measures? N europsychol

Salthouse,T. A., Hambrick, D.2., & Mct

tive and noncognitive variables. Ps

Salthouse, T. A., Toth, J. P., Hancock, H.

of memory and attention: Processp

Gerontology:PsychologicalSciences:

Spearman, C. (7927). The nature of intcl

Craik'sSelf-lnitiatedProcessingHypothesis 285

In 1I variables from 301 adults

';: ' correlation of .52. A studY

& :mith, 1998) contained data

.f \ .rnd a Spearmanrho of '91'

cl,,.elv resemblethe relations

111.,,riraYedin Figure 22'2. \n

r*ritude of the relation of the

ctr,,ns differ, becausewith the

to the amount of

6,,-1,'spsnds

:tr{rlrs the axis corresponds to

e\ ('r. the two situations maY be

inttrpreted as rePresentingthe

a.\ different tYPesof cognitive

rt'tlt'it the need to develoPand

'lr' .r)ntrol or allocation of attenr{ rt'presentsthis capability diler nrav representit indirectly if

t(' the extent that they relY on

i't. rnterPretedas emPirical evi,r,tht'sis.As Craik has predicted,

r. t ,rn somethingnecessarYfor

rt.r it should also be noted that

tcJ l.rocessinghypothesisrepre'

hat rs, positive AR relations are

..rriabies tend to be located tounri.er of analysesof this tYPe,

t. the uPPer right region ofthe

rt..r.oning tasks and PercePtual

r. .(,nsistent with the controlled

{\:Ins tasks can be assumed to

to solvea Probnir.\)f Processes

i,':1:tulProcessingto ensure effiMt)ll\'

t.r-f ,rrientedperspectivein conr r \ rdcncethat at least some age'

rrt .h.rred and are not comPletelv

et'Jt'rl to account for both shared

rn .,rgnitive aging. The discoven'

hr .rsc relation on a variable and

thrr \ariables(i.e.,AR functions)

f',1.i. for shared age-relatedinflu'

t .'..!()untfor these generaleffects

rt .iimension underlying the AR

' .rir-initiated processingrequired

n References

Anderson, N. D., Craik, F. I. M., & Naveh-Benjamin, M. (1998). The attentional demands of encoding

and retrieval in younger and older adults: 1. Evidence from divided attention costs. Psychology

and Aging, 1"3,405-423.

Craik, F. I. M. (1986). A functional account of age differences in rnemory. In F. Klix & H. Hagendorf

(Eds.), Human memory and cognitioe capabilities(pp. a09-a22\. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Craik, F. L M., & McDowd, l. M. (1987). Age differences in recall and recognition. Journal of ExperimentalPsychology:Learning,Memory and Cognition,13,474-479.

Craik, F. I. M., & Salthouse, T. A. (Eds.). (1992). Handbookof agingand cognition.Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Craik, F. I. M., & Salthouse,T. A. (2000). Handbookof agingand cognition(2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ:

Erlbaum.

jacoby, L. L. (1991).A processdissociationframework: Separatingautomatic from intentional usesof

memory. lournal of Memory and Language,30,573-541,.

Park, D. C., Davidson, N., Lautenschlagea G., Smith, A. D., & Smith, P. (1998, April) Differentation of

aisuo-spatialand aerbalworking memory and long-termmemory acrossthe life span. Paper presented

at the 1998 Cognitive Aging Conference, Atlanta, Georgia.

Park, D. C., Smith, A. D., Lautenschlager,G., Earles,J. L., Frieske, D.,Zwahr, M., & Gaines, C. L.

(1996). Mediators of long-term memory performance across the life span. Psychologyand Aging,

1.1.,62-t-637.

Salthouse,T. A. (1998).Independence ofage-related influences on cognitive abilities acrossthe life

span. DeoelopmentalPsychology,34, 851-864.

Salthouse,T. A. (2001). Structural models of the relations between age and measuresof cognitive

functioning. Intelligence,29, 93-775,

Salthouse,T. A., Fristoe,N., & Rhee, S. H. (1996).How localized are age-relatedeffectson neuropsychological measures?Neuropsychology,L0, 272-285.

Salthouse,T. A., Hambrick, D.2., & McGuthry, K. E. (1998).Shared age-relatedinfluences on cognitive and noncognitive variables. Psychologyand Aging, 13,486-500.

Salthouse,T. A., Toth, J. P., Hancock, H. E., & Woodard,J.L. (1.997).Controlled and automatic forms

of memory and attention: Processpurity and the uniqueness of age-related influences. Journal of

Gerontology : Psycholo gical Sciences, 528, P 21.6-P 228.

Spearman, C. (1927).The natureof intelligence'and the principlesof cognition.London: MacMillan.