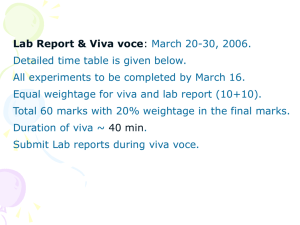

1 Case relating to fixation of marks for Oral Test:

advertisement