Information Technology Solutions

advertisement

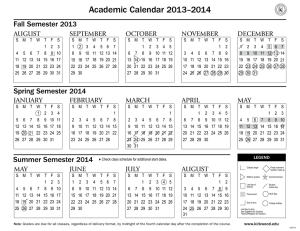

Information Technology Solutions Reaching the Kinesthetic Learner Ronda J. Rhoden El Paso Community College Teachership Academy March 25, 2013 1 Abstract The Action Research Project examined whether changes in teaching techniques helped kinesthetic learners increase their grades and reduce the number of their withdrawals. A survey determined students’ learning preferences and extroversion or introversion. Results indicated that adding non-traditional activities had a neutral effect upon both final grades and retention rates. This may have been a result of the author also being a kinesthetic learner. Implications from other research, however, remain valid: teachers at the college level need not only be encouraged, but also must receive training to use technology, as well as more hands-on, student-oriented and student-led activities. 2 Table of Contents Introduction 5 Teaching Styles ………………………………………………………………………….4 Learning Preferences/Styles …………………………………………………………..…5 Extroversion and Introversion …………………………………………………………...6 Web-enhanced Learning …………………………………………………………………6 Methodology 6 Course Requirements ……………………………………………………………………6 Table 1: Revisions in Course Requirements by Semester..……………………………...7 Demographic Information …………………………………………………………….....7 Collection of Data ……………………………………………….……………………….7 Figure 1: Survey 1 ………………………………………………………………………..8 Results 9 Student Personalities ………………………………………………………………….....9 Percentage of Letter Grades per Semester by Learning Preference and Student Personality ……………………………………………………………………………....9 Table 2: Extroverts’ Semester Grades and Percentages by Learning Style.…………….9 Table 3: Introverts’ Semester Grades and Percentages by Learning Style..…………….10 Table 4: Extroverts’ Semester Totals by Grades and Percentages…...………………….10 Table 5: Introverts’ Semester Totals by Grades and Percentages………………………..10 Table 6: Total Grades and Percentages by Semester……………………………………..11 Table 7: Percent Differences in Final Grades from Fall 2011 by Semester………………11 Discussion 11 Conclusion 13 Works Cited 14 Appendix 15 3 Introduction Teaching Styles Today’s economy has sent students back into colleges, universities, and technical schools in the hopes of increasing their earning power. Institutions of higher learning, as usual, wish to increase not only retention rates but also final grades, both of which indicate they are doing their job. The goal of this Research Action Project was to add activities that would not only engage students but also improve grades and retention rates. The method chosen to accomplish this goal was discovering students’ learning preferences and their introversion/ extroversion propensities. According to Fleming (1995), observations of the best teachers seem to indicate there is no single best way to teach. However, students’ final scores tend to be higher when teachers accommodate their students’ diverse needs by using multiple teaching approaches. As Fisher and Baird (2006) report, “the educational model needs to be reversed to conform to the learner, rather than [make] the learner [conform] to the system” (p. 5). Montgomery & Groat (1998) have come to believe that an understanding of learning styles can influence the teaching approaches of all instructors. They list four potential benefits: 1. By teaching and learning becoming a dialogue, lecture classes may include a variety of student-engaging active practices. 2. By varying responses in accordance with a more diverse student body, older students can draw upon life experience and be independent, ''self-directed” learners and women can learn in more "connected" ways. 3. By delivering information in a multi-faceted way and by considering student-learning styles, teachers may become invigorated and increase personal satisfaction. 4. By making what may be substantial changes, teachers can eliminate teaching traditions that are possibly counter-productive and ensure their teaching fields’ future. A final area that requires consideration in doing best by students is the mismatch between personalities. Faculty, 54% of whom are introverted, may have difficulty relating to the 76% of students who are extroverts. Likewise, the 30% of introverted students may face the same sorts 4 of obstacles in dealing with the 46% of extroverted faculty (Montgomery & Groat, 1998). Learning Preferences/Styles Research reveals students’ learning preferences and cognitive abilities “may play a significant role in overall preparation” (Ernst & Clark, 2008, p. 9), in other words, “people learn in different ways” (Fleming, 1995, p. 309), make different grades, stay or withdraw from classes depending upon whether their learning styles are met or not. Ernst and Clark (2008) found most professors teach in the way they learn or received instruction: even if these methods are not the best for their students. Some people show a definite learning preference, others have relatively weak secondary and/or tertiary choices. More than occasionally, there are dual or even haptic (triple) preferences. Two multi-modal students told Fleming (1995) that they “required input from at least two modes to get a ‘full understanding’ whereas those with a strong preference usually comment that one mode is enough” (p. 310). This aspect of learning styles was included in the research. The Learning Styles: Self-Assessment used in this study codes for three modes of learning. The first mode, designated auditory, learns by listening to speech as they interpret underlying meanings through vocal nuances. Reading aloud and using a tape recorder helps them learn (Fleming, 1995; The Vancouver Island Invisible Disability Association, n.d.; Rose, 1987). University teaching methods fail to reach the second (visual) genre, which desires graphs, charts, and flow diagrams. They tend to sit in front for they need to see body language and facial expression (Fleming, 1995; Rose, 1987; Vancouver Island, n.d.). “They are sensitive to different or changing spatial arrangements and can work easily with symbols” (Fleming, 1995, p. 309). The group studied in this Action Research Project, kinesthetics , like to experience their learning as they may become distracted sitting for long periods. They use all their senses and prefer concrete, multi-sensory means to explore the physical world. They learn theory and abstract material presented through analogies, real life examples, or metaphors. (Fleming, 1995; Vancouver Island, n.d.; Rose, 1987). Ultimately, Fleming (1995) states, In a tertiary education system we should feel sorry for the kinesthetics, who prefer . . . 5 field trips, experiments, role plays, games and experiential learning because those hands-on methods are seldom used. Problem-based teaching is also rare (p. 309). Extroversion and Introversion Due to class revisions during the Spring Semester of 2012, a second, intersecting area to study became apparent, the interaction of learning style and a student’s extraversion or introversion. Research indicates extraverted types learn best by discussing and/or working in groups, which helps them form, think through, and clarify their thoughts. They also do well when physically engaging the environment and producing visible results. Introverts learn best through quiet mental reflection. This allows them to figure things out and to understand the world before speaking. They tend to choose independent work – reading, lectures, and written work. While they may prefer not to talk, they enjoy discussions and will occasionally volunteer (Western Nevada College, 2012). Web-enhanced Learning The large majority of today’s students are “Millennials” (Larsen, n.d) born post-2000. Many grew up with Internet, multimedia, and have more than one web-accessible device. Students today expect to co-create and deliver content – to learn on “their terms, not those of a centralized authority, such as a teacher” (Fisher & Baird, 2006, p. 4). This not only pressures instructors to provide a quality education using highly interactive multimedia, but also to integrate user needs, learning style, and multiple intelligences (Fisher & Baird, 2006). Therefore, while not directly part of the research, all classes were required to use the web-enhanced learning management system, Blackboard. Methodology Course Requirements Classes included computer-enhanced teacher-prepared oral presentations replete with pictures, charts, videos, and application-descriptive analogies. Most students chose computer-enhanced modes of presentation and game delivery as well. The Blackboard management system delivered written assignments, with rubrics and samples. Assigned work was available for future 6 reference if needed. Following each semester’s results and using student suggestions, revisions in requirements occurred in the hopes of further enhancing learning. See Table 1. Demographic Information Participants were the author’s class members taking Introduction to Psychology, Human Sexuality, and/ or Human Growth and Development courses at El Paso Community College. The groups’ majors and ages varied. As a side note, as seems to be true for most if not all classes, pupils were primarily female. Unsurprisingly, a question added to Survey 1 (See Figure 1) about generational group, found most students were born between 1980 and 2000. Collection of Data The author followed Fleming (1995) by coding a strong learning preference/style as a score that was more than two points greater than any other learning preference’s score. A one or two point difference between highest and lowest score coded as bi-modal or haptic/balanced. Only data for learning preferences which included kinesthetic (i.e. kinesthetic, kinesthetic/visual, 7 8 kinesthetic/auditory, or haptic) are included in the study. Information collected included total numbers of stu- dents, number of extroverted and introverted students, as well as final grades and/or withdrawal status. Results Results were broken down by semester, by extrovert or introvert, by kinesthetic, kinesthetic/visual, kinesthetic/auditory, haptic, and by letter grade. Both numbers and percentages of each were determined. Student Personalities Among students who had kinesthetic learning preferences, the 2011 Fall Semester had 12 extroverts and 15 introverts. The 2012 Spring Semester comprised four each. During the 2012 Summer Semester, extroverts outnumbered introverts 18:3. The 2012 Fall Semester, extroverted: introverted were 64: 19. Spring 2013 numbered 41 extroverts and 9 introverts. Percentage of Letter Grades per Semester by Learning Preference and Student Personality Tables 2 and 3 summarize the grades and percentages of extroverted and introverted pupils respectively earning each letter grade according to their learning preference. 9 Comparisons of semester totals and percentages for Fall-to-Fall, Summer, and Spring-to-Spring follow in Tables 4 and 5. A final comparison lies in the total numbers and percentages of students making each letter grade irregardless of personality or learning preferences. See Table 6. 10 Ultimately, a final set of comparisons is that of examining the results by the percentage differences in final grades. This assessment included comparing Fall – Fall, and Spring – Spring semesters and then using the Fall 2011 Semester as a baseline with which to compare the succeeding semesters. The average percent change in final scores from the beginning of the study to the end of the study is included in Table 7. Discussion The most surprising finding was that the number of extroverted kinesthetics taking this author’s classes increased considerably each semester with the exception of Spring Semester of 11 2012. It may be that in attempting to reach and engage these students, the course requirement choices made appealed to extroverts and discouraged introverts. On the other hand, in talking with other students about which teacher to choose, introverts may have decided that the classes would be too emotionally draining. Cain (2011) offers another possible explanation: introverts spend so much of their lives conforming to extroverted norms by the time they answered the Survey it felt normal to ignore their own preferences – maybe some were actually introverts. Taking as a caveat that many of the F students actually should have withdrawn, fall semesters had the highest numbers of withdrawals. Possible explanations for this are 1) The fact that many of these are freshmen unprepared for taking responsibility for turning in their work and 2) Without receiving periodic report cards; they may not understand how to keep track of their grades on Blackboard despite receiving instruction about how to do so. In both the Spring Semester and Summer Semester of 2012, no one dropped the course, far lower than that of either Fall Semester 2011’s 22% or Spring Semester 2013’s 18%. The average change in drop rates was a decrease of 9.6%. Examining grades A - D, the Spring 2012 semester stands out with an abbreviated bell curve of 13% each for B’s and D’s with the remaining 75% of students earning C’s. The percentages for the remaining semesters’ grades remained fairly stable. A’s ranged from a high of 39% to a low of 0%, B’s 19% down to 13%, C’s 75% - 14%. D’s ranges were 19% high to 6% low while F’s were 22% - 10% lows. Inspecting average percent changes in these grades: A’s increased by 3.6%, B’s decreased by 3.2% while C’s increased by an average of 0.8%. D’s decreased by 3.2% and F’s by 5.4%. This suggests that kinesthetic students did increase the total percentage of their grades as hypothesized. See Table 7. Feedback from pupils was generally satisfying. 1) My lectures enhanced what the students presented and discussions provided; they missed them when time ran short. 2) With few exceptions, they reported they learned from hearing many peoples’ take on a subject and my lectures. 3) Many appreciated the opportunity to earn a grade by being required to review for exams. 4) The more creatively inclined enjoyed designing review games. 5) The majority 12 enjoyed the challenge (and the grades) in playing the games. 6) What they learned by actually observing and interpreting others’ actions surprised them. There were frequent complaints about the shortcomings of Blackboard and the amount of work required, yet students did the work when they had time – they always knew exactly what was due when. Conclusion This author’s conclusion is that the changed activities of class did enhance what was already being done, and brought more extroverts into classes. While the change may not have been as large as one might have liked, had all of this author’s students’ learning styles been included, or all students in all instructors teaching these same classes been included, the results may have differed. The five cycles in this Action Research Project did allow me critically to reflect on my own practice. They encouraged me to step outside the box of education as I had practiced it. Some of the changes were uncomfortable: 1) Giving up control of subject matter by allowing students to present their (guided) choice of topics, and 2) Teaching from a student seat in order to clarify a point in a student’s lecture or during the review games. I fully agree with (and paraphrase) Montgomery & Groat (1998): Ideally, we as faculty provide a variety of individual and group work, in order to address each learning style. This encourages innovation in faculty’s fields of interest. Accommodating all learning styles at some time helps faculty augment their methods of presentation. 13 Works Cited Cain, S. (2011). Quiet: The Power of Introverts How to thrive in a world that can’t stop talking. Available online http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/quiet-the-power-introverts/201103/quiz-are-you-introvert-orextrovert-and-why-it-matters. Ernst, J. V. & Clark, A. C. (Winter 2008). Students’ preferred learning styles in graphic communications. Engineering Design Graphics Journal. Vol (72) no. 1. Pp. 9 – 18. Fisher, M., Baird, D. E. (2006). Making mLearning work: Utilizing mobile technology for active exploration, collaboration, assessment, and reflection in higher education. Journal of Educational Technology Systems. Vol. 35(1). 3 – 30. Fleming, N.D. (1995). I’m different; not dumb. Modes of presentation (VARK) in the tertiary classroom, in Zelmer,A., (ed.) Research and Development in Higher Education, Proceedings of the 1995 Annual Conference of the Higher Education and Research Development Society of Australasia (HERDSA),HERDSA, Volume 18, pp. 308 – 313. Larsen, B. (n.d). Understanding generational diversity: Four generations. Available online at www.barbaralarsen.com. Montgomery, S. M. & Groat, L. N. (1998). Student learning styles and their implications for teaching. CRLT Occasional Papers. Vol. 10. 1-8. Rose, C. (1987). Adapted from Accelerated Learning. Retrieved 12/31/2004 from http://www.chaminade.org/ inspire/learnstl.htm The Vancouver Island Invisible Disability Association. (n.d.) Learning Styles: Simply Different Ways of Learning. LdPride.net Western Nevada College. (2012). Myer-Briggs Type Indicator Personality Types and Learning. Retrieved 10/6/2012 from http://www.wnc.edu/mbti/personality_ types_and_learning.php 14 Appendix 15