COUNCIL FOR ACCREDITATION OF COUNSELING AND RELATED EDUCATIONAL

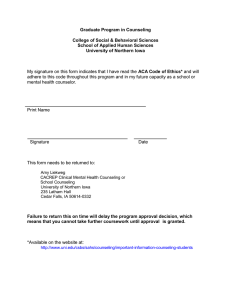

advertisement