The “Sect Effect” in Charitable Giving Distinctive Realities of Exclusively Religious By

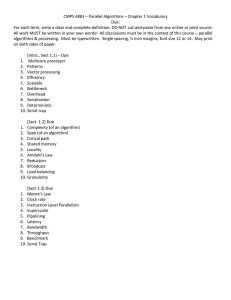

advertisement

The “Sect Effect” in Charitable Giving Distinctive Realities of Exclusively Religious Charitable Givers By RUSSELL N. JAMES III and DEANNA L. SHARPE* ABSTRACT. An examination of the charitable giving behavior of 16,442 households reveals intriguing patterns consistent with the clubtheoretic approach to religious sect affiliation. The club-theoretic model suggests that individuals with lower socioeconomic standing will rationally be more likely to align themselves with exclusivistic sects. Because sect affiliation is also associated with more obligatory religious contributions, this approach generates novel predictions not anticipated by standard economic models of charitable behavior. Traditional analysis of charitable giving can mask the “sect effect” phenomenon, as low-income giving is dwarfed by the giving of the wealthy. However, the application of a two-stage econometric model—separating the participation decision from the subsequent decision regarding the level of gifting—provides unique insights. Basic socioeconomic factors have significant and opposite associations with different categories of giving, calling into question the treatment of charitable giving as a homogenous activity and supporting the understanding of sect affiliation, and potentially religious extremism, as rational choice phenomena. The study of charitable giving, and in particular the religious component of charitable giving, holds the promise of generating significant insights when both economic and sociological perspectives are employed. Religious charitable giving is by far the largest and most *Russell N. James III, 203 Consumer Research Center, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602; e-mail Rjames@uga.edu. Dr. James’s research interests include charitable giving. Deanna L. Sharpe, 239-C Stanley Hall, University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia, MO 65211; e-mail SharpeD@missouri.edu. Dr. Sharpe’s research interests include consumer expenditure patterns and later-life economic issues and policy. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Vol. 66, No. 4 (October, 2007). © 2007 American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Inc. 698 The American Journal of Economics and Sociology widespread component of the more than $183 billion in annual donations made by individuals, exceeding all other forms of individual charitable giving combined (Giving USA 2003; Van Slyke and Brooks 2005). Religious charitable giving has continued to grow over the last several decades, expanding nearly 70 percent during the 1990s, with similar periods of rapid expansion during the 1970s and early 1980s (Giving USA 1999). Sociologically, the importance of religion has never been more apparent. From national security concerns and geopolitics to social capital measurements and family structure, religion’s impact is difficult to ignore. Because religious activity can take place in the context of close-knit, sometimes even secretive, nonmarket environments, empirical analysis can prove challenging. However, through the study of religious charitable giving, we have the opportunity to use advanced empirical tools on large data sets to help inform our understanding of underlying religious behavior. As voluntary gifts constitute 84 percent of all income to religious organizations in the United States, understanding charitable giving must be core to any serious examination of American religious organizations (Brooks 2004). I Background and Literature Review STUDIES OF CHARITABLE BEHAVIOR have often treated all types of charitable giving as homogenous or, in rare cases, have excluded religious giving altogether (Clotfelter 1985; Reece 1979). Notwithstanding this variation, research across several decades has repeatedly confirmed some persistent economic relationships. Charitable giving is income-elastic, and this elasticity holds even when the price effect from the increasing value of charitable tax deductions is held constant (Hrung 2004; Andreoni and Scholz 1998; Clotfelter 1980, 1985; Abrams and Schitz 1978; Taussig 1967). Greater wealth and education are consistently associated with increased giving (Schervish and Havens 2001; Brown and Lankford 1992; Kingma 1989; Schwartz 1970). Despite the well-established connections to income, wealth, and education, a club-theoretic approach to sect affiliation suggests a The “Sect Effect” in Charitable Giving 699 countervailing influence within certain groups of religious givers. A club-theoretic approach views congregations as mutual-benefit societies where members work collectively to produce “club goods” such as worship services, social activities, and religious instruction (Iannaccone 1998). The value of participation, however, depends on the positive externalities of other group members’ participation (Carr and Landa 1983; Sullivan 1985; Wallis 1990). Group norms for expected participation levels vary from group to group. The participation requirements, including obligations to give, tend to be strongest in more sect-like religious organizations. A “sect” is defined in foundational sociological literature as exclusive, small, ascetic, without a complex bureaucracy, rejecting or ignoring secular society and dominant churches, with intensely devoted, close-knit members, requiring committed, adult converts. In contrast, a “church” is inclusive, large, impersonal, bureaucratic, adjusting to existing social order, encompassing all who were born into it, possessing fewer means to obligate members to give (Troeltsch 1931; Weber [1905] 1989). Formally, we consider households maximizing an intertemporal utility function that depends upon both secular consumption, C, and religious activities, R: U = U (C1, C2, . . . . , Cn, R 1, R 2, . . . . R n ). Secular consumption utility depends upon the household inputs of time, Tc, and purchased goods, Xc, as well as on one’s stock of accumulated experience or “consumption capital,” Sc. Similarly, religious production depends not only on inputs of time and purchased goods but also on one’s accumulated experience in a particular religious tradition, itself being a function of past investments of time and purchased goods. In addition, religious production depends upon the positive externalities generated by the particular religious group to which one belongs (Iannaccone 1998). These positive externalities, Q, are a function of the m other members’ inputs of time, Tr, purchased goods, Xr, and accumulated experience, Sr: Ct = C( Tc, X c, Sc ) 700 The American Journal of Economics and Sociology R t = R ( Tr, X r, Sr; Q ) ΔSct = F ( Tct −1, X ct −1, Sct −1 ) ΔSrt = F ( Trt −1, X rt −1, Srt −1 ) Q = F ( Tr1, Tr 2, . . . Tr m; X r1, X r 2, . . . X r m; Sr1, Sr 2, . . . Sr m ) The effort to match desired individual religious participation levels (Tr, Xr, Sr) with club norms, Q, generates a spectrum of religious groups from high-cost “sects” to easygoing “churches” (Barros and Garoupa 2002). In order to maintain equilibrium in Q, highparticipation groups typically would enforce preexisting commitment minimums as a condition of continued membership. Maximization of members’ utility functions necessitates that groups be able to eliminate uncommitted “free riders” who absorb far more resources than they contribute. This is especially critical for sect-like groups with high average commitment levels, as member benefits can be substantial. Sect member benefits for those in need can include food, clothing, and shelter, as well as the status and affection that create a kind of “alternative society” (Stark and Bainbridge 1985). Of necessity, sectlike congregations are generally smaller and more adept at monitoring member activity to prevent free riding (Montgomery 1996; Iannaccone 1994). Thus, while sect members enjoy greater benefits, they are also subjected to more strictly enforced obligations, including, presumably, resource-appropriate financial contributions. Free riding also is prevented through successful enforcement of behavioral rules (perhaps of dress, diet, holiday observance, or other conduct) at odds with societal norms. The adoption of such behavioral rules provides an effective, easily monitored proxy for underlying commitment. In essence, sects present a convex production possibilities frontier between societal norms and sect expectations where only complete adherence or complete rejection are maximizing choices (see Iannaccone 1988 for this graphical model). Sect membership provides a high reward option, but one that is only available at the cost of rejecting societal norms. This “conduct and rewards” dichotomy makes a sect The “Sect Effect” in Charitable Giving 701 more attractive to those with diminished secular opportunities, as their opportunity costs for rejecting societal conduct norms are lower (Iannaccone 1992). Consistent with this optimization, we note that sects are populated predominantly by the lower classes and churches by the upper classes (Montgomery 1996). This finding is not new. Russell Dynes noted a significant correlation between low socioeconomic status and sectarian orientation in his 1955 sociological study. To the extent that blacks face fewer opportunities in mainstream society, we would rationally expect a higher proportion to choose sect membership. And, indeed, such racial connections have been documented (Argyle and BeitHallahmi 1975), including a particularly interesting study reviewing West Indian immigrants to Great Britain (Hill 1971). This study found that they commonly switched from more open church membership in their home country to exclusivistic Pentecostal sects after emigrating, hinting that relative secular opportunities, rather than any inherent racial differences, drive such affiliations. For the purposes of the present study, sect affiliation is most critical in its impact on religious charitable giving. One large study of Northern California church members captures this distinction, finding that: sect members are poorer and less educated; they contribute more money and attend more services; they hold stronger and more particularistic religious beliefs; their congregations are smaller yet are more likely to include their closest friends. The differences are strong, striking and statistically significant. (Iannaccone 1988: S242) A “sect effect” suggests that lower socioeconomic standing increases the probability of sect membership, which, in turn, generates a strong expectation of religious giving. Any such effect would be particularly interesting, given that the same socioeconomic factors associated with sect membership are otherwise related to a lowered probability for charitable giving. Naturally, this effect would be ascertained most clearly by separately examining religious and secular charitable givers. It is important to note that the proposed “sect effect” in religious charitable giving has no corollaries in the standard economic models of charitable giving. Several approaches to modeling charitable giving have been common in the literature, including a public goods game approach; the warm glow theory; the altruistic cooperative; and 702 The American Journal of Economics and Sociology prestige models. A public goods game approach, if used without the intervening construct of sect affiliation, makes no a priori predictions that any form of charitable giving would become more likely as socioeconomic standing decreases. Individual behavior is simply modeled as a game wherein each participant tries to contribute minimum resources for a maximum share of public goods. Having fewer resources does not, by itself, rationally increase the likelihood of contributing those scarce resources to any particular public goods game. The “warm glow” approach assumes that donors receive utility from the gift itself in the form of intangible benefits such as respect, social approval, relief from guilt, or a general good feeling (Andreoni 1993, 1995). Charitable giving may also be viewed more narrowly as a way to gain economic prestige where total utility is a function of goods consumption and one’s income level as perceived by others (Glazer and Konrad 1996). Yet, in either case, we would not naturally expect lower socioeconomic standing to increase the likelihood of purchasing either the prestige or “warm glow” effects through charitable gifts. Similarly, the altruistic cooperative proposed by Becker (1974, 1976), in which individuals cooperate either because of their own interdependent utility function or the interdependent utility function of another who contributes simultaneously to the individual and a third party, does not anticipate increasing altruism (real or simulated) for those with fewer economic resources. Indeed, the “sect effect” appears to be alone in predicting this counterintuitive behavior for a specific segment of religious charitable giving. II The Two-Stage Econometric Approach TO EXAMINE THE POSSIBILITY of a “sect effect” in religious charitable giving, we must be careful to use an approach that will not mask low-income charitable behavior through the dwarfing magnitude of charitable gifts by the wealthy. A particularly appropriate approach in the context of religious giving is to separate the decision to be a religious-cause giver from the decision regarding the amount of gift to be made. For example, it is unlikely that an atheist would make gifts to organized religion regardless of the changes in his or her income or The “Sect Effect” in Charitable Giving 703 the reduction in the (still positive) cost of the gift from tax benefits, whereas such factors would undoubtedly affect the level of gifting for someone with a different theological perspective. A separate analysis of the initial binary issue of participation versus nonparticipation also moderates the risk of large gifts from wealthy donors statistically dominating the giving behavior of less affluent givers. (See Schervish and Havens 1995 for an example of the importance of distinguishing charitable giving participation rates from charitable giving levels in statistical analysis.) Statistical models that differentiate between the participation decision and the level of consumption decision have been commonly employed in research of other types of consumer behavior (Garcia and Labeaga 1996; Cragg 1971). For example, many individuals would not purchase alcohol regardless of changes in their income or in the price of beer. Consequently, this consumption decision frequently is modeled using the two separate stochastic processes of the doublehurdle model (Sharpe et al. 2001). Similarly, demand models for tobacco consumption frequently employ double-hurdle models (Blaylock and Blisard 1992). Other applications of the double-hurdle have included consumption of cheese (Gould 1992), vegetables (Reynolds 1990), and shellfish (Lin and Milon 1993), as well as estimating demand for mortgages (Leece 1995). Previous statistical approaches to charitable giving necessarily had to deal with the reality that charitable giving data typically involve a high proportion of zero observations in the dependent variable (i.e., many people make no charitable gifts). Thus, these analyses commonly employed an ordinary least squares (OLS) lognormal, OLS translog, or Tobit model (Lankford and Wyckoff 1991). However, all of these models are restrictive in that an independent variable that increases the probability of a nonlimit observation also increases the mean of the dependent variable (Greene 1993). A double-hurdle model allows these two results to be independent. The factors associated with the decision to participate may be completely different from those that influence the level of consumption once participation is chosen. Indeed, a factor may even have opposite effects on the likelihood of participation and the level of participation. Such flexibility is critical, as we hypothesize lower economic resources 704 The American Journal of Economics and Sociology increasing the likelihood of sect participation, and hence religious charitable giving, while recognizing that diminished resources will ultimately have a negative impact on the potential level of giving. We examine separately religious and charitable giving by considering three groups of givers: those who make exclusively religious gifts; those who make exclusively secular gifts; and those who make both religious and secular gifts. Each charitable giver category is mutually exclusive; a decision to participate can be made in favor of only one category. Without this division, the desire to examine differences between those who give to religious organizations and those who give to other charitable organizations can be frustrated by the reality that these two groups include a large proportion of shared individuals. The separation of exclusive-giving groups allows us to examine those individuals not simultaneously participating in both giving categories. This separation facilitates an examination of the differences between those who give to religious organizations and those who give to other charitable organizations. As an additional benefit, the creation of a category for exclusively religious givers should help to bring special attention to the impact of sect members. That the exclusively religious giving category is more likely populated by sect members corresponds with previous observations of sect characteristics. For example, more sect-like denominations define a tithe as intended for support of the church only, whereas other denominations intend a tithe to be for both the church and other charitable causes. Higher denominational and individual religious strictness is commonly associated with participation in religious giving (Olson and Perl 2005; Lunn et al. 2001). Hoge et al. (1996) found that regular church attenders directed a lower percentage of their total giving to nonreligious charities and causes, while infrequent attenders gave higher percentages. In addition, sect members naturally would have the greatest impact on the “exclusively religious giver” category due both to a higher propensity to make religious gifts and to relatively lower financial resources for other forms of gifting. Our approach is identical to the Heckman complete dominance model, but we use it to ask two separate sets of questions. First, using probit analyses, we ask: “What factors are associated with the decision The “Sect Effect” in Charitable Giving 705 to be a particular type of giver (exclusively religious, exclusively secular, or mixed)?” Second, using a least squares analysis, we ask: “Among those who have chosen to be particular types of givers, what factors influence their nonzero level of giving?” This version of a double-hurdle model allows us to compare the factors that influence religious giving levels among exclusively religious givers as contrasted with mixed givers, as well as considering these same factors’ influence on secular giving levels among both mixed and exclusively secular givers. Because we are postulating the exclusively religious givers category as being more likely populated by, and representative of, sect members, this specification becomes particularly useful in allowing us to examine the behavior of this particular category’s members.1 The models for the first-stage investigation use three separate probit analyses with the dummy dependent variables of exclusively religious giver, exclusively secular giver, and mixed giver. The independent variables in each case are pretax income (natural log), number of minor children in the household, and age of the reference2 person (natural log), as well as the dummy variables of urban residence, level of education of the reference person, being black (as compared with being of another race), and being a single female or a single male (as compared with being married). The participation equation is: Pi = χ pi ′ βp + ε pi; ε pi ∼ n.i.d. (0, σ 2 p ) i = 1, . . . , N, where cpi is our vector of factors explaining variation in the participation for i = 1, . . . , N; N is the number of observations; bp is a vector of unknown parameters relating cpi to Pi,; and epi is the error term. The error term epi is assumed to be normally and independently distributed with a mean of zero. Because the participation equation measures the presence of category participation, not the nonzero level of participation, Pi is a binary variable. Pi is 1 if the ith unit is participating and 0 if it is not. Holding to the previously stated assumption about the error term, this first equation can be properly estimated using a probit analysis. The second stage of the analysis then focuses on the impact of these independent variables on the (nonzero) dollar level of gifting among individuals in each of the three different categories of givers. For 706 The American Journal of Economics and Sociology exclusively religious givers, this dollar level is the level of religious gifting. For exclusively secular givers, this is the level of secular charitable gifting. For mixed givers, we consider two separate regressions. One examines the level of religious giving, and another examines the level of secular charitable giving. Thus, this second-stage analysis involves a total of four different regressions within the three different subgroups of charitable givers. The expenditure equation is: Ci = χ ci ′ βc + ε ci; ε ci ∼ n.i.d. (0, σ 2c ) i = 1, . . . , N c. In this equation, cci is a vector of factors explaining variation in the expenditure level for i = 1, . . . , Nc; Nc is the number of observations excluding nonparticipants; bc is a vector of unknown parameters relating cci to Ci; and eci is the error term. The error term eci is assumed to be normally and independently distributed with a mean of zero. Here, Ci represents the nonzero dollar level of either religious or nonreligious charitable expenditures, depending upon the participation category. Ci is thus a continuous, positive variable. This expenditure level is estimated using a least squares regression analysis. In sum, we use probit analyses for participation in each of three, mutually exclusive, giving categories followed by least squares analysis for religious giving levels among exclusively religious givers, nonreligious giving among exclusively secular givers, religious giving among mixed givers, and nonreligious giving among mixed givers. Finally, these results are compared with an alternative standard (single-hurdle) model examining the overall impact of the independent variables on giving levels. Because 54 percent of our sample reported no contributions, we estimate these final giving functions with a Tobit specification censored at zero. We use three different Tobit models to separately examine the independent variables’ impact on total giving, religious charitable giving, and secular charitable giving. III The Data THE DATA ARE GATHERED from 16,442 separate households participating in the Consumer Expenditure Survey from 1998 to 2001. These include The “Sect Effect” in Charitable Giving 707 all complete income reporters who made a fifth-quarter report during the three-year period from the second quarter of 1998 through the first quarter of 2001. The Consumer Price Index was used to convert all dollar variables to constant 2001 dollars. Because questions regarding charitable expenditures were asked only in the fifth-quarter interview and each household completes only one fifth-quarter interview, no household is represented more than once in the sample. We label as “religious” gifting the amounts reported in response to the question: During the past 12 months, how much were contributions to church or other religious organizations, excluding parochial school expenses, made by you (or any members of your [household])? We categorize as “secular” giving the total of those amounts given in response to the following four questions: 1. During the past 12 months, how much were contributions to charities, such as United Way, Red Cross, etc., made by you (or any members of your [household])? 2. During the past 12 months, how much were contributions to educational organizations made by you (or any members of your [household])? 3. During the past 12 months, how much were political contributions made by you (or any members of your [household])? 4. During the past 12 months, how much were other contributions made by you (or any members of your [household])? We exclude from this study person-to-person gifts reported in response to the question: During the past 12 months, how much were gifts of cash, bonds, or stocks to persons not in the [household] made by you (or any members of your [household])? IV Results A. Summary Statistics Broad outlines of the type of contrasts predicted by a club-theoretic model of sect affiliation can be seen in the summary data. Income repeatedly has been shown to be positively associated with charitable giving. However, sect membership is negatively related to income. We 708 The American Journal of Economics and Sociology see the initial indications of this contrast in the descriptive statistics. At $66,292, mixed-giver households have a mean pretax income 39.5 percent above the sample average, while exclusively secular givers, at $62,057, average 30.6 percent more income than the typical household. In contrast, exclusively religious givers fall below the sample mean by more than 11 percent, with only $42,224 in pretax household income (see Table 1). Black racial status has been linked to lower charitable giving levels (Van Slyke and Brooks 2005). Yet to the extent that blacks face more limited opportunities from the dominant secular culture, the rational attractiveness of sect affiliation increases. Consistent with this predicted effect, we see a larger proportion of blacks in our exclusively religious giver category. A much larger share of exclusively religious givers are black (14.3 percent) than exclusively secular givers (5.4 percent). Indeed, blacks constitute a higher proportion of the exclusively religious givers category than any other category, also exceeding nongivers (12.4 percent), mixed givers (6.6 percent), and the sample as a whole (10.6 percent). Education has been repeatedly shown to be positively associated with charitable giving (Brown and Lankford 1992; Kingma 1989; Schwartz 1970). Higher education typically is associated with higher permanent income levels and thus indicates greater access to resources. Once again, however, sect theory predicts a counterbalancing effect, in that lower education levels are associated with sect membership and sect membership is linked to a higher likelihood of religious charitable giving. Again, we can see initial indications of this counterbalancing effect in the descriptive statistics. Having no high school diploma is less common among mixed givers (6.9 percent) and exclusively secular givers (8.6 percent) than among the sample as a whole (16 percent), but is more common among exclusively religious givers (17.8 percent). We see similar results at the higher end of the spectrum, where a greater proportion of exclusively secular givers (23.7 percent) and mixed givers (23.4 percent) have college degrees than the general sample (17.2 percent), while exclusively religious givers (15.6 percent) fall below the overall average. This trend continues as we see exclusively religious givers having less than the average proportion of graduate education while the other giving categories have more. -0-0-0- Relief giving Miscellaneous giving 2,668 $42,224 ($39,943) $1,223 ($2,071) $1,223 ($2,071) -0- Political giving Educational giving Religious giving Total giving N Pretax HH income Variable Exclusively Religious Givers 3,039 $66,292 ($58,594) $2,698 ($8,499) $1,891 ($5,458) $147 ($2,181) $30 ($211) $573 ($4,206) $57 ($790) Mixed Givers $57 ($348) $24 ($178) $334 ($1,125) $44 ($582) 2,508 $62,057 ($54,884) $459 ($1,380) -0- Exclusively Secular Givers Profiles of the Total Sample and the Four Subsamples Table 1 -0- -0- -0- -0- -0- 8,227 $37,898 ($38,520) Nongivers 16,442 $47,533 ($47,362) $767 ($3,920) $548 ($2,608) $36 ($949) $9 ($115) $156 ($1,875) $17 ($409) All The “Sect Effect” in Charitable Giving 709 Family size HH making education gifts HH making political gifts HH making relief gifts HH making miscellany gifts % of after-tax income given Tithers (giving 10%+ of after-tax income to any charity) Religion tithers (giving 10%+ of after-tax income to religion) Married HH Single female HH Single male HH Age of reference person Variable 21.3% 12.7% 88.6% 8.6% 4.5% 14.1% 10.4% 68.3% 22.0% 9.7% 53.2 (16.5) 2.6 (1.5) 11.7% 58.8% 29.8% 11.4% 49.9 (18.4) 2.7 (1.6) Mixed Givers -0-0-0-03.1% 11.7% Exclusively Religious Givers Table 1 Continued 55.0% 25.9% 19.1% 48.2 (16.1) 2.4 (1.3) -0- 15.7% 10.6% 84.8% 10.2% 0.8% 1.6% Exclusively Secular Givers 46.0% 31.7% 22.2% 45.7 (17.9) 2.5 (1.5) -0- -0-0-0-0-0-0- Nongivers 53.5% 28.7% 17.7% 48.2 (17.7) 2.5 (1.5) 3.8% 6.3% 4.0% 29.4% 3.1% 1.7% 4.7% All 710 The American Journal of Economics and Sociology HH with persons over 64 HH with persons under 18 Number under 18 in HH Education level Less than high school High school graduate Some college Bachelor’s degree Graduate education Black HH Urban HH 31.2% 34.8% 0.66 (1.07) 6.9% 23.6% 29.8% 23.4% 16.3% 6.6% 91.9% 28.3% 38.7% 0.77 (1.18) 17.8% 28.9% 31.5% 15.6% 6.1% 14.3% 88.9% 8.6% 25.3% 27.8% 23.7% 14.6% 5.4% 92.1% 20.3% 30.2% 0.53 (0.95) 21.1% 30.8% 28.7% 13.4% 6.0% 12.4% 90.8% 20.8% 37.0% 0.71 (1.12) 16.0% 28.3% 29.2% 17.2% 9.2% 10.6% 90.9% 23.9% 35.9% 0.69 (1.10) The “Sect Effect” in Charitable Giving 711 712 The American Journal of Economics and Sociology Overall, the demographic characteristics of our exclusively religious giving group mirror those of sect members. As discussed previously: “Theologically conservative denominations (typically labeled ‘fundamentalist,’ ‘Pentecostal,’ or ‘sectarian’) draw a disproportionate share of their members from among the poorer, less educated, and minority members of society” (Iannaccone 1998: n.6). Exclusively religious donors constitute about 15 percent of our data set. It is difficult to ascertain a comparable national number of those in more sect-like denominations. This exercise is challenging in part because there is no universally accepted taxonomy of “conservative,” “fundamentalist,” or “sect-like” denominations. The problem is compounded by broad denominational categories that include radical splinter groups and the presence of some 500 to 1,000 cults or alternative religions in the United States (Barker 1986). However, we can consider a rough comparison with the American Religious Identification Survey (Kosmin, Mayer, and Keysar 2001), which indicates that about 8 percent of Americans belong to Pentecostal, Charismatic, Assemblies of God, Churches of God, Churches of Christ, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Christian Scientist, Apostolic, Foursquare Gospel, or LatterDay Saints (Mormon) denominations, with another 16 percent belonging to some form of Baptist church. Similarly, General Social Survey data from 1989–1996 showed that about a quarter of individuals affiliate with “Baptist or conservative Protestant bodies (e.g., Assembly of God, Churches of Christ, Church of God in Christ, Nazarene, Pentecostal)” (Sherkat and Ellison 1999: 366) Such statistical comparisons are problematic for the current analysis, as we do not anticipate that all sect members will be exclusively religious givers or that all exclusively religious givers will be sect members. Rather, the expectation, based upon previous studies, is that sect members are more likely to engage in exclusively religious giving than others and hence will be heavily represented in this category. B. First-Stage Probit Analysis The first stage of the double-hurdle model investigates the impact of the independent variables on the likelihood of participation in a particular category of giving, without considering the level of participation. The “Sect Effect” in Charitable Giving 713 In particular, the first set of results explores the relationship of various independent variables to the likelihood of being an exclusively religious giver, an exclusively secular giver, or a mixed giver. The results shown in Table 2 display an immediate, substantial difference in the impact of certain variables on the likelihood of participating in the three different forms of charitable giving. In examining the impact of income, we see a direct contrast between exclusively religious givers and other types of givers. Greater income significantly increases the likelihood of exclusively secular giving and mixed giving but significantly decreases the likelihood of exclusively religious giving. In the area of race, we again see a direct contrast between exclusively religious and exclusively secular giving. For exclusively secular giving, black racial status is significant at the 0.001 level and decreases the likelihood of giving as compared with nonblack racial status. However, for exclusively religious giving, black racial status is also significant at the 0.001 level and increases the likelihood of giving. The contrast continues when we examine education. Having less than a high school education significantly reduces the likelihood of being an exclusively secular giver or a mixed giver but has no such impact on the likelihood of being an exclusively religious giver. Conversely, graduate education significantly reduces the likelihood of being an exclusively religious giver while significantly increasing the likelihood of being a mixed or exclusively secular giver. Once again, the results are consistent with the posited influence of sect membership within the exclusively religious charitable giving. C. Second-Stage Truncated Regression Analysis As we might expect, the level of giving among those who have made the decision to be givers is more similarly affected by economic factors. All of the significant variables are of the same sign, and we see little of the contrast revealed in the first-stage probit analysis.3 (See Table 3.) D. Tobit Analysis It is instructive to note that many of the most interesting “sect-effect” phenomena are masked when using a standard Tobit analysis. If we Bachelor’s degree Some college Education level of reference person Less than high school grad Single female reference person Single male reference person Black Ln (Income) -0.211*** (0.043) 0.023 (0.033) 0.179*** (0.037) 0.178*** (0.014) -0.323*** (0.048) 0.106 (0.036) 0.096 (0.032) -0.046*** (0.012) 0.248*** (0.037) -0.331*** (0.038) -0.105*** (0.03) 0.008 (0.826) 0.081 (0.031) -0.008 (0.825) (Probit) Probability of Being an Exclusively Secular Giver (Probit) Probability of Being an Exclusively Religious Giver Results of Probit Analysis for Charitable Giving Types Table 2 -0.397*** (0.044) 0.210*** (0.032) 0.328*** (0.036) 0.191*** (0.015) -0.122 (0.044) -0.351*** (0.039) -0.155*** (0.031) (Probit) Probability of Being a Mixed Giver 714 The American Journal of Economics and Sociology 0.241*** (0.044) 0.029 (0.044) -0.089*** (0.013) 0.044 (0.036) -3.079*** (0.211) 2,508 -6,739.12 -0.220*** (0.05) -0.127 (0.04) 0.041*** (0.012) 0.173*** (0.034) -1.042*** (0.19) 2,668 -7,164.68 0.426*** (0.043) 0.043 (0.043) 0.017 (0.013) 0.817*** (0.039) -6.119 (0.233) 3,039 -7,104.40 (Probit) Probability of Being a Mixed Giver N = 16,442. ***Estimate is significant at the 0.1% level (p < 0.001). Given the large N, we note only those having this very high significance level. Group members Log likelihood Constant Ln (age of reference person) Number of minor children in household Urban residence Graduate education (Probit) Probability of Being an Exclusively Secular Giver (Probit) Probability of Being an Exclusively Religious Giver Table 2 Continued The “Sect Effect” in Charitable Giving 715 Bachelor’s degree Some college Education level of reference person Less than high school graduate Single female reference person Single male reference person Black Ln (Income) Truncated Regressions (OLS) -234.26* (118.56) 367.04*** (102.32) 254.16* (125.89) 314.28*** (47.50) 190.84 (114.13) -502.39*** (134.86) -387.30*** (102.11) Religious Giving of Exclusively Religious Givers -50.47 (108.21) 121.75 (74.64) 261.09*** (78.94) 149.13*** (28.30) -40.88 (120.61) -74.64 (76.71) -82.69 (69.51) Secular Giving of Exclusively Secular Givers -44.50 (393.13) 295.66 (249.50) 673.14* (270.29) 313.04** (103.50) -343.16 (365.84) 344.04 (321.97) 10.06 (242.43) Secular Giving of Mixed Givers Results of Truncated Regression Analysis for Charitable Giving Levels Table 3 -199.99 (425.64) 406.46 (270.14) 778.72** (292.64) 719.54*** (112.06) 480.91 (396.10) 256.87 (348.60) -258.04 (262.49) Religious Giving of Mixed Givers 716 The American Journal of Economics and Sociology ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05. N R2 Constant Ln (age of reference person) Number of minor children in household Urban residence Graduate education 856.03*** (174.73) -4.87 (124.80) -1.97 (37.14) 335.75** (112.78) -3,308.07*** (672.27) 2,668 0.07 498.37*** (90.74) 183.58 (101.14) -39.57 (31.24) 326.35*** (83.81) -(2,652.24)*** (463.77) 2,508 0.05 1,609.01*** (298.00) -310.27 (333.10) -33.96 (97.43) 1,071.10*** (317.32) -6,969.92*** (1,798.51) 3,039 0.02 1871.76*** (322.65) -102.48 (360.65) 101.45 (105.49) 1,622.47*** (343.57) -12,776*** (1,947.25) 3,039 0.04 The “Sect Effect” in Charitable Giving 717 718 The American Journal of Economics and Sociology simply estimate the effect of a variable on the overall population’s level of giving without any separate examination of participation effects, the impact of large gifts by the wealthy can cover significant behavioral trends among poorer donors. The Tobit coefficients (see Table 4) simply provide the standard results, seen in numerous other studies, that overall charitable giving is positively related to income, education, age, and marriage. Separating religious giving from nonreligious giving in the Tobit analysis is a positive step. This separation reveals the significant and opposite impact of black racial status on religious and nonreligious giving. But the sect effect impacts seen in income and education remain hidden. Just as the impact of sect affiliation is highlighted by examining exclusively religious givers as a separate group, it is masked when we pool them with other, generally more affluent, donors in the traditional Tobit analysis. V Conclusions A. It May Be Inappropriate to Analyze Charitable Giving as a Homogenous Activity It is not uncommon for studies of charitable giving to treat all types of charitable gifts as essentially fungible, in other words, as a homogeneous type of consumer transaction. The dangers of such an approach are demonstrated in the significant and opposite relationships of basic socioeconomic variables such as income, education, and race to different categories of charitable giving. If two-thirds of a group is traveling north and one-third is traveling south, it is not necessarily appropriate to describe the group as moving north, slowly. And yet a statement that decreased income and education is associated with a decreased likelihood of charitable gifting creates a similarly deceptive impression. We know, for our sample at least, that specific kinds of charitable activity, such as the exclusive support of religious organizations, relate to fundamental socioeconomic variables in ways directly contrary to other forms of charitable giving, such as the exclusive support of secular charitable organizations. However, if we Graduate education Bachelor’s degree Some college Education level of reference person Less than high school Single female reference person Single male reference person Black Ln (Income) -839.77*** (157.35) 910.99*** (125.06) 1,132.38*** (144.84) 1,736.60*** (173.30) 569.13*** (54.50) 570.86*** (156.81) -1,757.67*** (150.38) -799.151*** (121.13) (Tobit) Religious Contributions -1,181.13*** (144.66) 568.72*** (106.70) 1,215.55*** (119.75) 1,986.87*** (140.48) 779.30*** (46.21) -929.02*** (150.10) -412.50*** (121.06) -169.56 (102.97) (Tobit) Secular Contributions Results of Tobit Analysis for Charitable Giving for Entire for Entire Sample Table 4 -1,146.18*** (173.62) 975.30*** (137.03) 1,617.89*** (157.47) 2,733.60*** (189.06) 915.08*** (58.30) -44.48 (176.66) -1,340.74*** (158.17) -589.19*** (132.19) (Tobit) All Contributions The “Sect Effect” in Charitable Giving 719 ***Estimate is significant at the 0.1% level. Noncensored observations Censored observations Log likelihood Constant Ln (age of reference person) Number of minor children in household Urban residence (Tobit) Secular Contributions 114.60 (142.56) -152.85*** (42.25) 1,936.96*** (122.49) -18,566.9 (727.50) 5,547 10,895 -57,883.56 (Tobit) Religious Contributions -203.76 (162.35) 171.34*** (47.21) 2,669.49*** (143.09) -18,940.8 (836.52) 5,707 10,735 -61,131.68 Table 4 Continued -139.36 (179.84) -2.54 (52.60) 2,824.65*** (153.80) -22,442.8*** (894.45) 8,215 8,227 -86,809.37 (Tobit) All Contributions 720 The American Journal of Economics and Sociology The “Sect Effect” in Charitable Giving 721 were to examine only the Tobit analysis on overall charitable giving levels, we would see little to indicate the presence of this sect effect among exclusively religious donors. No doubt these distinctions can make descriptions more cumbersome, but the presence of multiple, highly significant relationships of opposite sign provide strong evidence that generalizations of charitable giving as a whole run the risk of ignoring important realities within specific classes of donors. It is also worth mentioning that we can’t simply say that religious givers are poorer and less educated, because mixed givers—also a class of religious givers—are, in our sample, demonstrably wealthier and more educated than both exclusively secular givers and the sample as a whole. B. The “Sect Effect” Provides a Potential Theoretical Basis for These Notable Results The curious result that participation in a certain class of charitable giving is made more likely by the presence of reduced income, lowered education, and black racial status is not predicted by the standard economic theories on charitable giving. In the absence of the club-theoretic model of sect affiliation, we might have some difficulty putting together a coherent theoretical underpinning for this unusual consumer behavior. Yet, these results are clearly consistent with the posited club-theoretic sect affiliation model. Sects provide a high reward option, but one that is only available at the cost of rejecting societal norms. Those with relatively lower secular opportunity costs should rationally be drawn to the sect value proposition. Lower income, less education, and black racial status all point to the likelihood of fewer societal opportunities. As predicted, these same factors are all associated with an increased likelihood of exclusively religious charitable giving, our posited proxy for sect-consistent behavior.4 C. A Rational Choice Model of Religion May Be Appropriate for Future Policy Considerations Recently, religious extremism has been associated with a variety of violent and offensive behaviors of geopolitical significance. Nobel 722 The American Journal of Economics and Sociology Laureate Gary Becker modeled the typical responses to offensive behavior as increasing the probability or magnitude of punishment (Becker 1968). These responses fall short, however, when religious extremists engage in intentional martyrdom, harming others in the process. In these situations, despite absence of government or other public policy intervention, the probability and magnitude of the punishment for the extremist (death) are high. Results of this study suggest that other responses to offensive religious behavior may warrant consideration. Specifically, if religious behavior is viewed as an irrational, exogenous, unmanageable constant, then we are unlikely to recognize the power of underlying economic factors in encouraging such extremism. A rational choice model of sect affiliation suggests that the future martyr’s initial decision to affiliate with the extremist group may have resulted from rational choice. As such, it may be worthwhile to consider the circumstances that made the initial affiliation appear to be utility-maximizing. For example, Iannaccone (2000), following an argument earlier presented by Adam Smith in the Wealth of Nations, discusses how an open religious market structure allowing the free formation of religious groups may reduce extremism by providing a wider array of strictness choices, instead of only extremes. Evidence that religious affiliation flows from rational choices—rather than being an irrational, exogenous factor—strengthens the value of such policy considerations. Notes 1. Other double-hurdle specifications examine the impact of an independent variable on the overall level of consumption in the population as a whole. Here our model’s use is dictated by the particular question being asked, that is: Given that an individual is in a particular participation category, how do various factors influence the level of participation? We specify this second question to explore differences among different category members in what influences nonzero levels of giving. For questions examining the impact of an independent variable on the overall level of consumption in the population as a whole, the standard complete dominance model is appropriate where the participation and consumption equations are independent (Heckman 1979; Blaylock and Blisard 1993). 2. The reference person is the first member mentioned by the respondent when asked to “[s]tart with the name of the person or one of the persons who owns or rents the home” (U.S. Dept. of Labor 2003: 250). The “Sect Effect” in Charitable Giving 723 3. The R 2 values are quite low in this analysis. As our goal in this second stage is to examine the impact of the independent variables at issue, rather than using the model to successfully predict the ultimate level of giving, we can perhaps be slightly less concerned with this issue. Nevertheless, these standard socioeconomic variables appear to be doing a poor job of explaining the variation in the ultimate giving levels among those who have chosen to be certain types of givers. 4. We see similar results even among those who are mixed givers. An ordinary least squares regression on the proportion of giving dedicated to religion within this mixed group, using the same dependent variables as our probit model, finds negative association of income [-0.01048 (0.00532)], bachelor’s-level education [-0.02771 (0.01389)], and graduate-level education [-0.08661 (0.01531)] while finding positive association of black racial status [0.12632 (0.018800)]. References Abrams, B., and M. Schitz. (1978). “The ‘Crowding-Out’ Effect of Governmental Transfers on Private Charitable Contributions.” Public Choice 33(1): 29–39. Andreoni, J. (1993). “An Experimental Test of the Public-Goods Crowding-Out Hypothesis.” American Economic Review 83(5): 1317–1327. ——. (1995). “Cooperation in Public-Goods Experiments: Kindness or Confusion?” American Economic Review 85(4): 891–904. Andreoni, J., and J. K. Scholz. (1998). “An Econometric Analysis of Charitable Giving with Interdependent Preferences.” Economic Inquiry 36: 410–428. Argyle, M., and B. Beit-Hallahmi. (1975). The Social Psychology of Religion. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Barker, E. (1986). “Religious Movements: Cult and Anticult Since Jonestown.” Annual Review of Sociology 12: 329–346. Barros, P. P., and N. Garoupa. (2002). “An Economic Theory of Church Strictness.” Economic Journal 112: 559–576. Becker, G. (1968). “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach.” Journal of Political Economy 76(2): 169–217. ——. (1974). “A Theory of Social Interactions.” Journal of Political Economy 82(6): 1063–1092. ——. (1976). The Economic Approach to Human Behavior. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Blaylock, J., and W. Blisard. (1992). “U.S. Cigarette Consumption: The Case of Low-Income Women.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 74: 698–705. ——. (1993). “Women and the Demand for Alcohol: Estimating Participation and Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 27: 319–334. 724 The American Journal of Economics and Sociology Brooks, A. C. (2004). “The Effects of Public Policy on Private Charity.” Administration and Society 36(2): 166–185. Brown, E., and H. Lankford. (1992). “Gifts of Money and Gifts of Time: Estimating the Effects of Tax Prices and Available Time.” Journal of Public Economics 47: 321–341. Carr, J., and J. Landa. (1983). “The Economics of Symbols, Clan Names, and Religion.” Journal of Legal Studies 12(1): 135–156. Clotfelter, C. (1980). “Tax Incentives and Charitable Giving: Evidence from a Panel of Taxpayers.” Journal of Public Economics 13: 319–340. ——. (1985). Federal Tax Policy and Charitable Giving. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Cragg, J. (1971). “Some Statistical Models for Limited Dependent Variables with Application to the Demand for Durable Goods.” Econometrica 39: 829–844. Dynes, R. R. (1955). “Church-Sect Typology and Socio-Economic Status.” American Sociological Review 20: 555–560. Garcia, J., and J. Labeaga. (1996). “Alternative Approaches to Modelling Zero Expenditure: An Application to Spanish Demand for Tobacco.” Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 58(3): 489–506. Giving USA: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 1999. (1999). Glenview, IL: AAFRC Trust for Philanthropy. Giving USA: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2003. (2003). Glenview, IL: AAFRC Trust for Philanthropy. Glazer, A., and K. Konrad. (1996). “A Signaling Explanation for Charity.” American Economic Review 87: 1019–1028. Gould, B. (1992). “At-Home Consumption of Cheese: A Purchase-Infrequency Model.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 74: 178–189. Greene, W. H. (1993). Econometric Analysis. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co. Heckman, J. J. (1979). “Sample Selection Bias as a Specification Error.” Econometrica 47(1): 153–162. Hill, C. (1971). “From Church to Sect: West Indian Religious Sect Development in Britain.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 10: 114–123. Hoge, D. R., C. E. Zech, P. D. McNamara, and M. J. Donahue. (1996). Money Matters: Personal Giving in American Churches. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox. Hrung, W. B. (2004). “After-Life Consumption and Charitable Giving.” American Journal of Economics and Sociology 63(3): 731–745. Iannaccone, L. (1988). “A Formal Model of Church and Sect.” American Journal of Sociology 94: S241–S268. ——. (1992) “Sacrifice and Stigma: Reducing Free-Riding in Cults, Communes and Other Collectives.” Journal of Political Economy 100: 271–292. The “Sect Effect” in Charitable Giving 725 ——. (1994) “Why Strict Churches Are Strong.” American Journal of Sociology 99(5): 1180–1211. ——. (1998). “Introduction to the Economics of Religion.” Journal of Economic Literature 36: 1465–1496. ——. (2000). “Religious Extremism: Origins and Consequences.” Contemporary Jewry 20: 8–29. Kingma, B. (1989). “An Accurate Measurement of the Crowd-Out Effect, Income Effect and Price Effect for Charitable Contributions.” Journal of Political Economy 97(5): 1197–1207. Kosmin, B. A., E. Mayer, and A. Keysar. (2001). American Religious Identification Survey. New York: City University of New York. Lankford, R., and J. Wyckoff. (1991). “Modeling Charitable Giving Using a Box-Cox Standard Tobit Model.” Review of Economics and Statistics 73: 460–471. Leece, D. (1995). “Rationing, Mortgage Demand and the Impact of Financial Deregulation.” Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 57(1): 43–66. Lin, J., and J. Milon. (1993). “Attribute and Safety Perceptions in a DoubleHurdle Model of Shellfish Consumption.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 75: 724–729. Lunn, J., R. Klay, and A. Douglass. (2001). “Relationships Among Giving, Church Attendance and Religious Belief: The Case of the Presbyterian Church (USA).” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 40(4): 767–775. Montgomery, J. D. (1996). “The Dynamics of the Religious Economy: Exit, Voice and Denominational Secularization.” Rationality and Society 87: 81–110. Olson, D. V. A., and P. Perl. (2005). “Free and Cheap Riding in Strict, Conservative Churches.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 44(2): 123–142. Reece, W. (1979). “Charitable Contributions: New Evidence on Household Behavior.” American Economic Review 89(1): 142–151. Reynolds, A. (1990). “Analyzing Fresh Vegetable Consumption from Household Survey Data.” Southern Journal of Agricultural Economics 22: 31–38. Schervish, P. G., and J. J. Havens. (1995). “Do the Poor Pay More: Is the U-Shaped Curve Correct?” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 24(1): 79–90. ——. (2001). “Wealth and the Commonwealth: New Findings on Wherewithal and Philanthropy.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 30(1): 5–25. Schwartz, R. (1970). “Personal Philanthropic Contributions.” Journal of Political Economy 78: 1264–1291. Sharpe, D., M. Abdel-Ghany, H. Kim, and G. Hong. (2001). “Alcohol Consumption Decisions in Korea.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 22(1): 7–24. 726 The American Journal of Economics and Sociology Sherkat, D. E., and C. G. Ellison. (1999). “Recent Developments and Current Controversies in the Sociology of Religion.” Annual Review of Sociology 25(1): 363–395. Stark, R., and W. Bainbridge. (1985). The Future of Religion. Berkeley: University of California Press. Sullivan, D. (1985). “Simultaneous Determination of Church Contributions and Church Attendance.” Economic Inquiry 23(2): 309–320. Taussig, M. (1967). “Economic Aspects of the Personal Income Tax Treatment of Charitable Contributions.” National Tax Journal 20: 1–19. Troeltsch, E. (1931). The Social Teaching of the Christian Churches. New York: Macmillan. U.S. Dept. of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2003). Consumer Expenditure Survey, 2002: Interview Survey and Detailed Expenditure Files [Computer File]. ICPSR Release. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics [Producer]. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research [Distributor], 2005. Van Slyke, D. M., and A. C. Brooks. (2005). “Why Do People Give? New Evidence and Strategies for Nonprofit Managers.” American Review of Public Administration 35(3): 199–222. Wallis, J. (1990). “Modeling Churches as Collective Action Groups.” International Journal of Social Economics 17(1): 59–72. Weber, M. ([1904/1905] 1989). The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. London: Unwin Hyman.