Health Divide: Economic and Demographic Factors Associated

advertisement

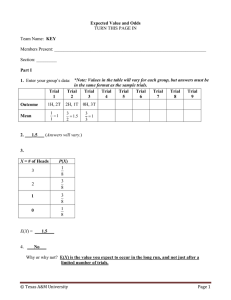

J Fam Econ Iss (2010) 31:328–337 DOI 10.1007/s10834-010-9207-2 ORIGINAL PAPER Health Divide: Economic and Demographic Factors Associated with Self-Reported Health Among Older Malaysians Sharifah Azizah Haron • Deanna L. Sharpe Jariah Masud • Mohamed Abdel-Ghany • Published online: 9 June 2010 Ó Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 Abstract Data from the 2004 Survey of Economic and Financial Aspects of Aging in Malaysia were analyzed to determine factors associated with self-reported health status among older Malaysians. Odds of self-reporting health as bad versus moderate or good were higher for respondents who were in lower income quintiles, who perceived their financial situation as bad, who were older and who were not married. Malay, Chinese, Indian, and Bumiputra ethnic groups had lower odds of perceiving their health to be bad as compared with those in other ethnic groups. Keywords Asian Health inequality Health status Older Malaysians Introduction Between 1990 and 2001, the life expectancy of men and women in Malaysia lengthened by almost 3 years (68.8– S. A. Haron J. Masud Department of Resource Management and Consumer Studies, Faculty of Human Ecology, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia e-mail: sh.azizah@putra.upm.edu.my J. Masud e-mail: jariah@putra.upm.edu.my D. L. Sharpe (&) Personal Financial Planning Department, University of Missouri-Columbia, 239 Stanley Hall, Columbia, MO 65211, USA e-mail: sharped@missouri.edu M. Abdel-Ghany Consumer Sciences Department, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487, USA e-mail: mabdel-g@ches.ua.edu 123 71.4) and 6 years (70.3–76.0) respectively (Abdel-Ghany 2008; Department of Statistics 2008; Economic Planning Unit 2002). This increase in life expectancy does not necessarily indicate an improvement in the health status of older Malaysians, however. Although declining health is not an inevitable consequence of aging, older individuals constitute the majority of those with health problems (Grundy and Sloggett 2003). Consequently, as the proportion of older persons in the Malaysian population increases, their health status becomes a concern. As such, identifying determinants of health status and health inequality among older Malaysians is of interest to researchers and policy makers. Health status has been measured in various ways. Some researchers have focused on objective measures of health such as the presence of a specific disease (e.g. diabetes, heart disease), observed levels of physical or mental functioning, or mortality rates (i.e. Kivimaki et al. 2003). Although objective measures provide important information about health status, they often depend on technical assessment by a trained professional and can be narrow in scope. Therefore, objective health measures might be less effective as assessments of global health status, as well as difficult to implement in survey research of broad populations. Respondents’ subjective rating of their own health has been used as an alternative, especially in health research in gerontology (e.g. Baron-Epel and Kaplan 2001; Grundy and Sloggett 2003). Although the efficacy of selfreported health status has been debated, it has support in the literature as a viable alternative to objective assessments (Baker et al. 2001; Idler and Benyamini 1997; Kim and Lyons 2008; Meer et al. 2003; Miilunpalo et al. 1997). Health inequality refers to differences in health status between two or more groups that are distinguished by some salient characteristic such as income level, gender, or J Fam Econ Iss (2010) 31:328–337 ethnicity (Todd 1996). Marked inequalities in health status have been described as a health divide when such inequality aligns with differences in economic status or social class to highlight the rift between haves and havenots (Whitehead 1987). Previous studies have found evidence that disparities in health status can originate from differences in individual internal factors such as health history and genetics as well as from inequalities in external factors such as physical environment and living conditions (i.e. Palloni 2000; Todd 1996). To date, studies that have examined determinants of health status have largely focused on western developed countries such as the United States or Europe (e.g. Carlson 2004; Starfield and Shi 2002) or on developing countries (e.g. Marmot 2005). Little attention has been given to Asia in general or to Malaysia in particular. This study addresses this gap in the literature, focusing on older Malaysians. Specifically, this study uses data from the 2004 Survey of Economic and Financial Aspects of Aging in Malaysia to examine the factors associated with self-reported health status of Malaysians aged 55–70. Age 55 is considered normal retirement age in Malaysia, so this age grouping captures the early years of retirement (Masud et al. 2008). Understanding determinants of health variation in later life is important because older individuals’ health status largely determines their ability to remain independent and autonomous (Arber and Ginn 1993). Also, identification of factors associated with health disparities can point to potential ways to narrow the gap in health status between certain groups. Older Malaysians are of particular interest because government statistics indicate that this group has the highest incidence of poverty in the country (22%) (Eight Malaysia Plan 2001). A significant link between poverty and poor health outcomes is widely supported in the literature (Smith 1999). In addition, older Malaysians are a heterogeneous group that differ considerably in religious belief and practice, cultural background and socioeconomic status; all factors which may affect health-related behavior. Literature Review Health Status The health history of older persons as well as their access to satisfactory medical care influences their current health status (Palloni 2000). Health history chronicles the influence that biological, environmental, behavioral, lifestyle and psychological factors have on a person’s health and well-being (Palloni 2000). For example, risk of contracting serious illness can depend on such things as early childhood exposure to health risks (e.g. quality of prenatal care), 329 lifetime behavioral risk profiles (e.g. habits of smoking or exercising), or past use of health inputs (e.g. taking a vitamin supplement) (Palloni 2000). Health status can be assessed objectively or subjectively. Objective indicators of health status include physician reports and assessment of physical capacity (e.g. mobility and muscle strength), motor performance and psychological functioning. Subjective measures utilize perception and self-ratings of one’s own general health to indicate one’s sense of well-being (Grundy and Sloggett 2003). Baron-Epel and Kaplan (2001) proposed that older individuals form their perception of their own health by comparing their current health status with: (1) their own health at other times, (2) health status of other people of the same age, and (3) health status of other people that have the same illness. They noted that the last two comparisons could help explain the positive health perceptions that older persons often have even when experiencing serious or debilitating illness. The most commonly used subjective health measure is a single item that asks study participants to rate their present health status using a five-point Likert-type scale that ranges from ‘‘very good’’ or ‘‘excellent’’, ‘‘good,’’ ‘‘fair,’’ ‘‘poor,’’ to ‘‘very poor’’ (i.e. Grundy and Sloggett 2003; Ren 1997; Sargent-Cox et al. 2008). To capture a broader view of survey respondent health, researchers have used various alternatives to a single scale measure (Mete 2004). Some have used several scales. For example, Sargent-Cox et al. (2008) used three scales. Respondents used the first scale to rate their current overall health status. Using the second scale, respondents compared their current health status to that of others their age. With the third scale, respondents compared their current health status to their own past health status. Taking another approach, some researchers have asked respondents to rate general and specific aspects of their health. For instance, in a study of health inequality, Grundy and Sloggett (2003) asked respondents for selfreport of presence and duration of long-standing illness along with a self-report of general health. Still another approach has been to use both objective and subjective health assessments. For example, Rautio et al. (2005) considered physician report of respondent’s blood pressure, ECG performance, sensory and motor performance and psychological functioning along with respondent selfreport of health. Although the reliability and validity of self-reported health measures has been debated, there is evidence across a number of studies that such measures offer a reliable assessment of actual health status (Baker et al. 2001; Idler and Benyamini 1997; Kim and Lyons 2008; Meer et al. 2003). Zimmer et al. (2005) found support for using a general self-assessment of health to predict mortality. They argue, similar to Baron-Epel and Kaplan (2001), that self- 123 330 assessment of health status reflects not only current health status, but a lifetime of experience that allows comparison of current health status to one’s past health status and to the health status of others. Relationship Between Socioeconomic Characteristics and Health Prior research has identified significant relationships between health status and education, economic resources, age, gender, ethnicity and, marital status (Adler and Newman 2002; Hayward et al. 2000). Higher levels of education attainment have been consistently associated with better health status across various health measures (Baron-Epel and Kaplan 2001; Murrell and Meeks 2002; Masud et al. 2006). Education level reflects the quantity and quality of resources that were available early in life (Murrell and Meeks 2002) and influences subsequent occupation, financial and social resources, and better selfcare through middle age and older adulthood, which could contribute to better health in later life. Considerable attention has been given in the literature to the empirical relationship between income and health status (i.e. Nummela et al. 2007; Smith 1998). There is evidence of a reciprocal relationship. Considering health as a determinant of economic resources, Smith and Kington (1997) found that older individuals with excellent health had 2.5 times more household income and five times more wealth than older individuals with poor health. In a similar vein, Kim and Lyons (2008) found that medical expenditures made by older individuals in poor health placed a significant drain on financial resources. Some studies (e.g. Wilkinson 1996; Ullah 1990) have indicated that the subjective experience of financial strains is more closely related to health status than it is to the actual level of income. Conversely, economic resources can be viewed as a determinant of health status. For example, poverty can influence health outcomes through several mechanisms including detrimental early life conditions, inadequate use of or access to medical care, injurious health behaviors, environmental exposure to toxins or poor working conditions (Williams and Collins 1995). Functional disability is associated with advanced age (e.g. Ng et al. 2006). Rampal et al. (2008) concluded that the prevalence of hypertension increased with age in both men and women. Nummela et al. (2007) found that those aged 52–56 in both rural and urban areas reported the best self-rated health, as compared with their older counterparts. Gender differences in health status of older individuals have been found. In a study of the problems of older Malaysians, Masud et al. (2006) noted that although more than half of all the respondents rated their health as good, the older men in the study were more positive about their 123 J Fam Econ Iss (2010) 31:328–337 health than the older women. Arber and Cooper (1999), on the other hand, found that self-assessment health measures showed minimal gender differences until age 80. Ethnicity represents differences in biological, demographic, and social environment as well as psychological and behavioral characteristics that contribute to one’s health (Lillie-Blanton and Laveist 1996). Hamid et al. (2006) noted among Malaysian elderly, the Chinese had the longest lifespan followed by Malays and Indians. Indians had lower life expectancy than the national average for males of 70 years (Hamid et al. 2006). Lee et al. (2009) noted that, in Malaysia, Malays and Indians fared worse than other ethnic groups in hospital admissions and mortality for congestive heart failure. They concluded that racial differences might exist in the rate of disease progression or response to drug therapy. Or, socio-cultural beliefs and knowledge levels might differ, which would affect treatment compliance and, eventual outcome. Culture may also affect use of various forms of self-care. For example, Aziz and Tey (2008) found that the odds of Malay using herbal medicine were 1.35 times higher than Chinese and 5.81 times higher than Indians. Marital status is closely associated with health condition. As compared with the married, the unmarried tend to have higher age-adjusted mortality rates from all causes of death, use more health services (Verbrugge 1979), have a higher level of psychological distress (Wertlief et al. 1984), and assess their global health and well-being as relatively worse than the married (Mauldon 1990). Ren (1997) noted that, as compared with the married, the separated, divorced, and cohabiting were all more likely to report poor health (2.23 times, 1.31 times, and 1.35 times, respectively). But, Bos and Bos (2007) found Brazilian widows were 20% more likely than married women to report better health. Methods Data The data used in this study were from the 2004 Economic and Financial Aspects of Aging in Malaysia funded by the Intensified Research Priority Area (IRPA), Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, the government of Malaysia. A multistage random sampling approach was used. First, the total number of older persons in different age categories in each mukim (county/territorial division) within each state in Peninsular Malaysia was obtained from the Department of Statistics, Malaysia. From this sample, 6% of the mukims with the highest proportion of older individuals were selected. A total of 3,000 older persons between ages 55 and 70 were systematically selected from J Fam Econ Iss (2010) 31:328–337 these mukims to participate in the survey. Of these, 2,327 responded, for a response rate of 78%. One person per household was surveyed. In married couples, the typical respondent was the husband. The data were collected through personal interviews conducted by trained enumerators. Questionnaires were developed in four languages: Malay, English, Mandarin (Chinese) and Tamil to facilitate interviews with the different ethnic groups in Malaysia. Data were obtained from 1,296 Malay (51% male, 49% female); 523 Chinese (52% male, 48% female), 162 Indian (38% male, 62% female) and 346 other (51% male, 49% female). Conceptual Framework Health status pertains to individual characteristics (e.g. genetic disorders), as well as to private and social investment in health capital (Grossman 1972; Pincus et al. 1999). The latter is especially important when considering the health status of Malaysians who were born before or near Malaysia’s independence in 1957. At that time, agriculture was the primary base of the Malaysian economy, educational opportunity was limited, and money income for most households was quite low (United Nations Development Programme 2007). The rapid transformation of the Malaysian economy to an industrial and information base has had little direct effect on the economic circumstances of Malaysians age 50 and older, due largely to their low levels of education and limited job skills (United Nations Development Programme 2007). Based on economic theory and prior research, human capital, economic, and demographic variables are used to explain differences in self-reported health status of Malaysians age 55–70. Of particular interest in this study is ascertaining whether there is evidence of a health divide, that is, a significant difference in health status between those with relatively higher or lower resource levels. Empirical Model The model dependent variable was self-reported health status; categories were ‘‘bad,’’ ‘‘moderate,’’ or ‘‘good.’’ Since the response variable was comprised of multiple categories, multinomial logit was used to estimate the effect of the independent variables on the log odds of reporting a good, moderate or bad health condition. The logistic model was specified as: Log½P=1 P ¼ b0 þ b1 E þ b2 Y þ b3 D þ e where P was the probability that a respondent reported moderate or bad health (good health was the reference category). E represented human capital, Y represented level of economic resources, and D represented a set of 331 demographic variables that included age, gender, ethnicity and marital status. Variable Measurement Dependent variable coding was based on survey respondents’ answer to the question: ‘‘How would you rate your present state of health?’’ Bad health was coded 1 if a respondent indicated ‘‘bad,’’ 0 otherwise. Similarly, moderate health was coded 1 if a respondent indicated ‘‘moderate,’’ 0 otherwise. Good health was the reference category. Education was used as a proxy for human capital. Since this birth cohort would have had low levels of education, it was measured by a dummy variable set equal to 1 if the respondent had a primary education or less, 0 otherwise. Malaysia follows the British education system. Primary school, for children age 7–12, consists of standard one through standard six and corresponds to first to sixth grade in the American education system. Objective and subjective measures of income were used to proxy economic resources. The objective measure was respondent report of own income measured as annual amount of Malaysian ringgits (RM) (at time of this study 1 RM = $3.60 US) received from salary or wages, profit from business, pension, rental income, transfers from sons, transfers from daughters, transfers from grandchildren or other relatives, agricultural sales, dividends, bonuses, annuities, or other sources. Reported income was recoded into income quintiles to indicate respondent’s relative position within the income distribution of the sample. The subjective measure of financial status was respondent answer to the question: ‘‘How would you rate your present financial situation?’’ Possible responses were ‘‘bad,’’ ‘‘moderate,’’ and ‘‘good (reference category).’’ Dichotomous variables were created for bad and moderate, each set equal to 1 for those giving that response, 0 otherwise. The subjective assessment of income status was included in this study to provide a perspective of income adequacy from the respondent’s point of view. The demographic variables in this study were age, gender, ethnicity, and marital status. Age was a continuous variable. Given the relatively longer life spans of women, gender was coded 1 if female, 0 otherwise. Malaysia has several distinct ethnic groups, each with their own history, culture, dominant religion, and social customs. Ethnicity was coded as a series of dummy variables. Malay was coded 1 if Malay, 0 otherwise. Chinese was coded 1 if Chinese, 0 otherwise, Indian was coded 1 if Indian, 0 otherwise. Sabah and Sarawak natives were coded as Bumiputra (1 if yes, 0 otherwise). The name ‘‘Bumiputra’’ means ‘‘the son of soil,’’ referring to the original inhabitants of the country prior to the colonization era. Other 123 332 J Fam Econ Iss (2010) 31:328–337 ethnic groups, which would be any ethnicity other than those specified, were the reference category. Given potential for a relatively large number of widows among the older women in the sample, marital status was coded 1 if not married, 0 otherwise. Findings and Discussion Sample Characteristics The socio-demographic characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 1. As expected, slightly over a third of respondents (34.6%) had no formal education. Close to half (46.6%) had only a primary education. Somewhat less than 20% had completed secondary education, whereas only 1.2% has completed tertiary education. About 31% of the older individuals in the sample were in the bottom 40% of income quintile. A large percentage of the study respondents (30.1%) clustered within the middle-income quintile, whereas about 19% of study respondents belonged to the top income quintile. Interestingly, despite the large percentage with relatively low income levels, only 12% of survey respondents perceived their financial situation to be ‘‘bad.’’ The remainder of the respondents either rated their financial situation as moderate (46%) or good (42%). The mean age of the respondents in the sample was 63.47 years old. The sample had almost equal proportion of males (50.6%) and females (49.4%). At 55%, Malays Table 1 Socio demographic background and perception of health status All sample (n = 2,327) Freq/mean %/SD Health perceptions Chi-square/F-value Bad (n = 400) Moderate (n = 837) Good (n = 1,090) Freq/mean Freq/mean Freq/mean %/SD %/SD %/SD Highest education obtained No formal education 806 34.6 206 25.6 308 38.2 292 36.2 1,085 46.6 157 14.5 387 35.7 541 49.9 408 17.6 34 8.3 137 33.6 237 58.1 28 1.2 3 10.7 5 17.9 20 71.4 Quintile 1 468 20.1 117 25.0 167 35.7 184 39.3 Quintile 2 267 11.5 57 22.3 94 40.6 116 37.0 Quintile 3 700 30.1 145 19.5 284 37.6 271 42.9 Quintile 4 460 19.8 55 12.0 173 37.6 232 50.4 Quintile 5 432 18.6 26 6.0 119 27.5 287 66.4 279 1,061 12.0 45.7 118 191 42.3 18.0 106 486 38.0 45.8 55 384 19.7 36.2 980 42.2 88 9.0 242 24.7 650 66.3 64.87 5.623 Primary education Secondary education Tertiary education 97.291** Quintile 128.946** Perception of financial situation Bad Moderate Good Mean age 63.47 5.729 63.95 5.702 62.59 5.647 353.929** F = 28.525** Sex Male 1,178 50.6 174 14.8 400 34 604 51.3 Female 1,149 49.4 226 19.7 437 38 486 42.3 20.812** Ethnicity Malay 1,296 55.7 214 16.5 488 37.7 594 45.8 Chinese 523 22.5 74 14.1 183 35.0 266 50.9 Indians 162 7.0 20 12.3 56 34.6 86 53.1 Bumiputra 337 14.5 88 26.2 107 31.8 142 42.2 9 0.4 4 44.5 3 33.4 2 22.3 Other ethnic groups 33.995** Marital status Not married Married Divorced/separated ** p \ 0.01 123 47 2.0 15 31.9 12 25.5 20 42.6 1,532 748 65.8 32.1 212 173 13.8 23.1 522 303 34.1 40.5 798 272 52.1 36.4 65.247** J Fam Econ Iss (2010) 31:328–337 represented the largest ethnic group, followed by Chinese (22.5%), Bumiputra (14.5%), Indians (7.0%) and others (0.4%). These figures correspond to national population data for older persons aged 50 and above stratified by ethnic group—47% Malay, 35% Chinese, 9% Bumiputra, 7% Indian and 0.87% other ethnic groups (Department of Statistics 2008). Most sample respondents were married (65.8%). Interestingly, almost a third of respondents (32.1%) reported being divorced or separated, of which most were women. Self-Reported Health Table 1 presents respondent’s health perception by their socio demographic background. About half (47%) of the respondents assessed their health as good, 36% rated their health as moderate and 17% rated their health as bad. The percentage distribution of older individuals who perceive their health as good was higher for those with higher levels of education. Specifically, 71% of older individuals with tertiary education assessed their health as ‘‘good’’ as compared with 58, 49.9 and 36.2% of those with secondary, primary and those with no formal education, respectively. The converse was true for those who perceived their health as moderate. In this situation, those without formal education formed the highest percentage of those who judged their health condition to be moderate. A similar distribution pattern is observed between income quintile and health perception. In general, the percentage of those rating their health as ‘‘good’’ was relatively higher for those in the higher income quintiles. These findings are consistent with previous research that confirmed a positive relationship between income level and health status (Nummela et al. 2007; Smith and Kington 1997). Interestingly, the perception of older respondents regarding their health aligned with their perception of their financial situation. Specifically, the highest percentage of those who perceived their financial situation as bad also judged their health as bad (42.3%). Similarly, the highest percentage of those who perceived their financial situation as moderate or good, also perceived that their health as either moderate (45.8%) or good (66.3%), respectively. Such findings correspond with Kim and Lyons’ (2008) work that suggested financial stain is a consequence of poor health. The mean age of the sample that judged their health as good or moderate (62.59 and 63.95, respectively) was smaller than the mean age of the sample that judged their health as bad (64.87 years old). This finding supports the idea that health condition and hence self-rating of health, decline with age. 333 Findings indicated gender differences in health perception exist. A slightly higher percentage of male (51%) as compared with female (42.3%) perceived their health as good. Conversely, a relatively higher percentage of females (19.7%) as compared with males (14.8%) judged their health status as bad. These findings are consistent with that of Masud et al. (2006) who found that older men were more positive about their health as compared with women. Also, women were living longer but had more health problems than men. Respondents perceiving their health as ‘‘good’’ comprised the highest percentages across all ethnic groups. The percentage of Indians who rated their health as good is the highest of all ethnic groups (53%), followed by Chinese (51%) and Malay (46%). The percentage of respondents that rated their health as moderate was the highest among Malays (37.7%), followed by Chinese (35%) and Indian (34.6%). Bumiputra and other ethnic groups formed the highest percentage (26.6%) among those who rated their health as bad followed by the Malays (16.5%). An interesting pattern emerged when health perception was analyzed across marital status. The highest percentage (32%) of those who perceived their health as bad were among those who never married; the divorced and separated formed the highest percentage among those who perceived their health as moderate, while the majority of older individuals who assessed their health as good (52%) were currently married. These findings were consistent with Ren (1997) who found that older individuals that were divorced, separated or cohabiting reported having relatively poorer health as compared with those who were married. Ren (1997) cautioned, however, that such perceptions may depend more on the quality of marriage than on marital status alone. Factors Influencing Health Perception Table 2 summarizes the result of the multivariate logit analysis. To facilitate understanding, discussion of results for those who rated their health as ‘‘bad’’ or ‘‘moderate’’ is presented in separate sections: 1. Older individuals who rate their health as ‘‘bad’’ Among those who rated their health as ‘‘bad’’ the following variables were found significant: income quintile, financial perception, age, ethnicity, and marital status. The odds for those who were in the lowest income quintile was 2.90 times as high as the odds for those who were in the highest income quintile to rate their health as bad instead of good. The odds for those who were in the second lowest income quintile was 2.36 times as high as the odds for those who were in the highest income quintile to rate their health as bad instead of good. The odds for those who were in the third income quintile was 3.11 times as high as the odds for 123 334 J Fam Econ Iss (2010) 31:328–337 Table 2 Result of multivariate logit on perception of health Variable Respondent perception of own health Bad b Moderate Std Error Wald Sig level Exp (b) b Std Error Wald Sig level Exp (b) Education: (Ref C secondary) Primary education or less Income quintile (Ref = Q5) Q1 0.253 0.216 1.361 1.066 0.268 15.777 Q2 0.859 0.289 8.811 Q3 1.135 0.252 20.214 Q4 0.586 0.268 4.778 0.243 1.287 -0.034 0.138 0.060 0.806 0.967 1.332 7.13E-05 2.903 0.287 0.179 2.568 0.109 0.003 2.359 0.190 0.197 0.935 0.334 1.210 6.93E-06 3.111 0.560 0.157 12.691 0.000 1.750 0.029 1.797 0.348 0.160 4.734 0.030 1.41 Perception of financial standing (Ref = good) Bad 2.504 0.207 146.809 8.6E-34 12.233 1.568 0.187 70.494 4.62E-17 4.797 Moderate 1.273 0.149 72.767 1.46E-17 3.574 1.235 0.105 139.487 3.45E-32 3.439 Age 0.051 0.012 19.330 1.1E-05 1.053 0.037 0.009 17.170 3.42E-05 1.038 -0.141 0.144 0.956 0.328 0.869 -0.184 0.109 2.859 0.091 0.832 Malay -2.435 0.973 6.259 0.012 0.088 -1.074 0.950 1.278 0.258 0.342 Chinese -2.572 0.978 6.919 0.009 0.076 -1.195 0.952 1.577 0.209 0.303 Indian -2.987 1.006 8.826 0.003 0.050 -1.303 0.964 1.825 0.177 0.272 Bumiputra -2.078 Marital status: (Ref = married) 0.982 4.477 0.034 0.125 -1.219 0.958 1.618 0.203 0.296 Sex: (Ref = male) Female Ethnicity: (Ref = other) Not married 0.467 0.151 9.524 0.002 1.594 Intercept -3.923 1.214 10.448 0.0012 – -2 Log likelihood 3996.2 those who were in the highest income quintile to rate their health as bad instead of good. The odds for those who were in the second highest income quintile was 1.80 times as high as the odds for those who were in the highest income quintile to rate their health as bad instead of good. The odds for those who rated their financial situation as bad, to rate their health as good instead of bad was 12.23 times as high as the odds for those who rated their finances as good. The odds for those who rated their finances as moderate, to rate their health as good instead of bad, was 3.57 times as high as the odds for those who rated their finances as good. For age, the odds of rating health as bad instead of good increased by 1.05 times with 1 year increase in age. As for ethnicity, the odds for Malays is 0.09 times as high as the odds for those who were classified as others to rate their health as bad instead of good. The odds for the Chinese was 0.08 times as high as the odds for those who were classified as others to perceive their health as bad instead of good. The odds for Indians was 0.05 times as high as the odds for those who were classified as others to perceive their health to be bad instead of good. The odds for ‘‘other Bumiputra’’ is 0.12 times as high as the same odds for those who were 123 0.300 0.120 6.270 0.012 1.350 -2.499 1.097 5.188 0.023 – classified as others to perceive their health to be bad instead of good. The odds for those who were not married was 1.59 times as high as the odds for those who were married to rate their health as bad instead of good. 2. Older individuals who rated their health as ‘‘moderate’’ The odds for those who were in the third income quintile was 1.75 times as high as the odds for those who were in the highest income quintile to rate their health as moderate instead of good. The odds for those who were in the second highest income quintile was 1.42 times as high as the odds for those who were in the highest income quintile to rate their health to be moderate instead of good. The odds for those who rated their financial situation to be bad, to rate their health to be moderate instead of good, was 4.80 times as high as the odds for those who rated their finances as good. The odds for those who rated their finances to be moderate, to rate their health moderate instead of good is 3.44 times as high as the odds for those who rated their finances as good. The odds of rating health as moderate instead of good increased by 1.04 times with a 1-year increase in age. The odds for those who were not married was 1.35 times as J Fam Econ Iss (2010) 31:328–337 high as the odds for those who were married to rate their health as moderate instead of good. Conclusion This study used data from the 2004 Survey of Economic and Financial Aspects of Aging in Malaysia to examine the factors associated with self-reported health status of Malaysians aged 55–70. The study provides insights into the circumstances of a population group that has received little attention in prior literature on health inequality. Study findings indicate that there is a health divide among older Malaysians. Income appears to be the main dividing factor, although age, ethnicity, and marital status also play a role. Those who were in the lower income quintiles and those who perceived their financial standing to be bad were significantly more likely to also rate their health as bad. Odds of rating health as bad were also greater for older individuals, those of ‘‘other’’ race, and single individuals. Interestingly, when other factors were controlled, neither education nor gender had a significant influence on self-reported health status. Results of this study have several implications. First, the presence of different levels of health among older Malaysians indicates that members of this group do not fare equally well. Consequently, attention must be given to potential reasons for differential health status among this population group. Second, study findings imply that the health status of older Malaysians cannot be attributed to the aging process alone. The influence of economic and social factors on health status must be considered as well. Those interested in improving the health status and consequent quality of life of older Malaysians should note that, of the factors found significantly related to health level in this study, income is the key factor that would be amenable to change via public policy. Given the significant link between poverty and poor health indicated in the literature (Smith 1999), exploring means of improving the financial status of low income older Malaysians would appear to be an important policy goal. Finally, education and gender were not significant factors in explaining health differences among older Malaysians. This finding is contrary to prior research, suggesting that this birth cohort may have some unique characteristics. Indeed, we know this is the case. Respondents in this study witnessed a remarkable and relatively rapid transformation of the Malaysian economy from agriculture to industry and technology. Their low levels of education and training limited their opportunity to participate in the gains from that change, however, a problem not uncommon to developing economies (Fuess and Hou 2009). Further research is needed to determine whether the economic development that Malaysia has 335 experienced since independence in 1957 will serve to widen or narrow this health divide for future generations. The relatively low levels of economic resources of the current older generation suggest that they will need financial support during their remaining years (Rubin and White-Means 2009; Sheng and Killian 2009; Ulker 2009), whether from family, community, or government sources. References Abdel-Ghany, M. (2008). Problematic progress in Asia: Growing older and apart. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 29, 549–569. Adler, N., & Newman, K. (2002). Socioeconomic disparities in health: Pathways and policies. Health Affairs, 21(2), 60–76. Arber, S., & Cooper, H. (1999). Gender differences in health in later life: The new paradox? Social Science and Medicine, 48, 61–76. Arber, S., & Ginn, J. (1993). Gender and inequalities in health in later life. Social Science Medical, 3(1), 33–46. Aziz, Z., & Tey, N. P. (2008). Herbal medicines: Prevalence and predictors of use among Malaysian adults. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 17(1), 44–50. Baker, M., Stabile, M., & Deri, C. (2001). What do self-reported, objective, measures of health measure? NBER Working Paper 8419. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Baron-Epel, O., & Kaplan, G. (2001). General subjective health status or age-related subjective health status: Does it make a difference? Social Science and Medicine, 53, 1373–1381. Bos, A. M., & Bos, A. J. (2007). The socio-economic determinants of older people’s health in Brazil: The importance of marital status and income. Aging and Society, 2(3), 385–406. Carlson, P. (2004). The European health divide: A matter of financial or social capital? Social Science and Medicine, 59, 1985–1992. Department of Statistics. (2008). Yearbook of Statistics Malaysia 2007. Putrajaya: Department of Statistics. Economic Planning Unit. (2002). Kualiti Hidup Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: Prime Minister Department. Eight Malaysia Plan: 2001–2005. (2001). Malaysian Department of Statistics. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysia Government Printing Office. Fuess, S. M., & Hou, J. W. (2009). Rapid economic development and job segregation in Taiwan. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 30, 171–183. Grossman, M. (1972). On the concept of human capital and the demand for health. Journal of Political Economy, 80(2), 223– 255. Grundy, E., & Sloggett, A. (2003). Health inequalities in the older population: The role of personal capital, social resources and socio-economic circumstances. Social Science and Medicine, 56, 935–947. Hamid, T. A., Ahmad, Z. S., Abdul Rashid, S. N., & Mohamad, S. (2006). Older population and health care system in Malaysia: A country profile. Serdang: Penerbit Universiti Putra Malaysia. Hayward, M. D., Crimmins, E. M., Miles, T. P., & Yang, Y. (2000). Status in explaining the racial gap in chronic health conditions. American Sociological Review, 65, 910–930. Idler, E. L., & Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38, 21–37. Kim, H.-S., & Lyons, A. (2008). No pain, no strain: Impact of health on the financial security of elderly Americans. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 42(1), 9–36. 123 336 Kivimaki, M., Head, J., Ferrie, J. E., Shipley, M. J., Vahtera, J., & Marmot, M. G. (2003). Sickness absence as a global measure of health: Evidence from mortality in the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. British Medical Journal, 327, 364–369. Lee, R., Chen, S.-P., Cahn, Y.-H., Wong, J., Lau, D., & Ng, K. (2009). Impact of race on morbidity and mortality in patients with congestive heart failure: A study of the multiracial population in Singapore. International Journal of Cardiology, 134(3), 422–425. Lillie-Blanton, M., & Laveist, T. (1996). Race/ethnicity, the social environment and wealth. Social Science and Medicine, 43, 83–91. Marmot, M. (2005). Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet, 365, 1099–1104. Masud, J., Haron, S. A., & Gikonyo, L. W. (2008). Gender differences in income sources of the elderly in Peninsular Malaysia. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 29, 623–633. Masud, J., Haron, S. A., & Hamid, T. A. (2006). Perceived income adequacy and health status among older persons in Malaysia. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 18(suppl), 2–8. Mauldon, J. (1990). The effect of marital disruption on children health. Demography, 27, 431–446. Meer, J., Miller, D. L., & Rosen, H. S. (2003). Exploring the healthwealth nexus. Journal of Health Economics, 22(5), 713–730. Mete, C. (2004). Predictors of older mortality: Health status, socioeconomic characteristics and social determinants of health. Health Economics, 14(2), 135–148. Miilunpalo, S., Vuori, I., Oja, P., Pasanen, M., & Urponen, Hl. (1997). Self-rated health status as a health measure: The predictive value of self-reported health status on the use of physician services and on mortality in the working-age population. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 50(5), 517–528. Murrell, S. A., & Meeks, S. (2002). Psychological, economic and social mediators of the education–health relationship in older adults. Journal of Aging Health, 14, 522. Ng, T.-P., Niti, M., Chian, P.-C., & Kua, E.-H. (2006). Prevalence and correlates of functional disability in multiethnic older Singaporean. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 54(1), 21–29. Nummela, O. P., Sulander, T. T., Heinonen, H. S., & Uutela, A. K. (2007). Self-rated and indicators of SES among the ageing in three types of communities. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 35, 39–47. Palloni, A. (2000). Living arrangement of older persons. Madison: Center for Demography and Ecology, University of Wisconsin. http://www.un.org. Pincus, T., Esther, R., DeWalt, D., & Callahan, L. F. (1999). Social conditions and self-management are more powerful determinants of health than access to care. Annals of Internal Medicine, 129(5), 406–411. Rampal, L., Rampal, S., Azhar, M. Z., & Rahman, A. R. (2008). Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in Malaysia: A national study of 16,440 subjects. Public Health, 122, 11–18. Rautio, N., Heikkinen, E., & Ebrahim, S. (2005). Socio-economic position and its relationship to physical capacity among older people living in Jyväskylä, Finland: Five- and ten-year follow up studies. Social Science and Medicine, 60, 2405–2416. Ren, X. S. (1997). Marital status and quality of relationship: The impact on health perception. Social Science Medical, 44(2), 241– 249. Rubin, R. M., & White-Means, S. I. (2009). Informal caregiving: Dilemmas of sandwiched caregivers. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 30, 252–267. Sargent-Cox, K. A., Anstey, K. J., & Luszcz, M. A. (2008). Determinants of self-rated health items with different points of references: Implications for health measurement of older adults. Journal of Aging Health, 20, 739–761. 123 J Fam Econ Iss (2010) 31:328–337 Sheng, X., & Killian, T. S. (2009). Over time dynamics of monetary intergenerational exchanges. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 30, 268–281. Smith, J. P. (1998). Socioeconomic status and health. Informing Retirement-Security Reform, 88(2), 192–196. Smith, J. P. (1999). Healthy bodies and thick wallets: The dual relation between health and wealth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13(2), 145–166. Smith, J. P., & Kington, R. (1997). Race, socioeconomic status and health in late life. In L. Martin & B. Soldo (Eds.), Racial and ethnic differences in health of older Americans (pp. 106–162). Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Starfield, B., & Shi, L. (2002). Policy relevant determinants of health: An international perspective. Health Policy, 60, 201–218. Todd, A. (1996). Health inequalities in urban areas: A guide to the literature. Environment and Urbanization, 8(2), 141–152. Ulker, A. (2009). Wealth holdings and portfolio allocation of the elderly: The role of marital history. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 20, 90–108. Ullah, P. (1990). The association between income financial strain and psychological wellbeing among unemployed youth. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63, 317–330. United Nations Development Programme. (2007). Malaysia: Measuring and monitoring poverty and inequality. Kuala Lumpur: United Nations Development Programme. Verbrugge, L. (1979). Marital status and health. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41, 267–285. Wertlief, D., Budman, S., Demby, A., & Randall, M. (1984). Marital separation and health: Stress and interventions. Journal of Human Stress, 10, 18–26. Whitehead, M. (1987). The health divide. London: Health Education Council. Wilkinson, R. G. (1996). Unhealthy societies: The afflictions of inequality. London: Routledge. Williams, D. R., & Collins, C. (1995). U.S. socio-economic and racial differences in health: Pattern and explanations. Annuals Review of Sociology, 21, 349–386. Zimmer, Z., Martin, L. G., & Lin, H.-S. (2005). Determinants of oldage mortality in Taiwan. Social Science and Medicine, 60, 457– 470. Author Biographies Sharifah Azizah Haron, Ph.D., IFPÒ is an Associate Professor in the Department of Resource Management and Consumer Studies, Faculty of Human Ecology at the University of Putra Malaysia, specializing in Consumer and Family Economics. Her research focuses on consumer behavior, empowerment, wellbeing and policy, as well as household economic well-being and poverty. She has served on the Malaysian national review committee for the Consumer Protection Act and as a member of the National Council of Consumer Advisory. She is currently involved in the formulation of Consumer Master Plan of Malaysia. She serves on the editorial board of the Malaysian Journal of Consumer and Family Economics. Deanna L. Sharpe, Ph.D., CFPÒ is an Associate Professor in the Personal Financial Planning Department at the University of Missouri. Her teaching and research center on factors affecting later life economic well-being, including labor supply, family resource management, financial planning, consumer expenditure patterns, retirement savings behavior, and financial planner/client relationships. She has won five Outstanding Paper awards. She is a past board member of the American Council on Consumer Interests and the Association of Financial Counseling and Planning Education. She has J Fam Econ Iss (2010) 31:328–337 served on the CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNERTM exam review team, the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Education Task Force, and has been an invited participant to the U.S. Department of the Treasury National Symposium on Financial Education Research. She serves on the editorial boards of the Journal of Family and Economic Issues, the Journal of Financial Planning and Counseling, and the Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. Jariah Masud, Ph.D. is a Professor Emeritus in Management and Family Economics, specializing in gender issues and poverty of the aged. She is currently a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Gerontology, University of Putra Malaysia. Her research focuses on family economics and financial well-being of the elderly, women’s role in the economy, gender and development. She has been actively involved in poverty, consumer and gender-related training, consultancy and advisory at the national and international level, and in the formulation of national policies such as the National Policy of the Aged, Consumer Master Plan of Malaysia and National Family Policy. She serves on the editorial board of the Malaysian Journal of Consumer and Family Economics, Malaysian Journal of Family Studies, and Malaysian Journal of Consumers and Journal of Islamic Education. 337 Mohamed Abdel-Ghany, Ph.D. is a Professor Emeritus in the Consumer Sciences Department at the University of Alabama. He is serving a third consecutive term as Associate Editor of the Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal. He has published more than 115 refereed articles in several journals and conference proceedings. He is a Distinguished Fellow of the American Council on Consumer Interests, and Distinguished Research Fellow of International Society for Quality of Life Studies. He is the 1998 recipient of the Family Economics Research Award (American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences). He served as a President of the American Council on Consumer Interests, the Asian Consumer and Family Economics Association, and Vice-President of Professional Affairs for International Society for Quality-of-Life Studies. He has served as a member of the Editorial Board of Journal of Consumer Affairs, Journal of Consumer Studies and Home Economics, Journal of Family and Economic Issues, International Journal of Consumer Studies, Malaysian Journal of Consumer and Family Studies, and the Family Economics and Nutrition Review. 123