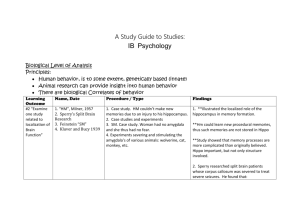

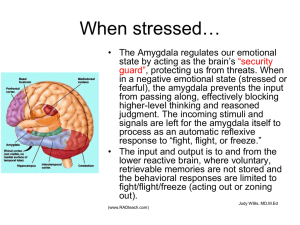

The Amygdaloid Complex: Anatomy and Physiology

advertisement