Kinds of Scientific Rationalism: The Case for Methodological Liberalism by

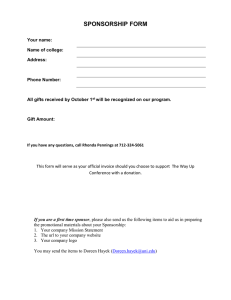

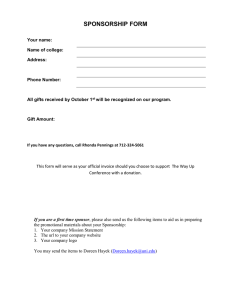

advertisement