Friedrich Hayek and his Visits to Chile by Bruce Caldwell and

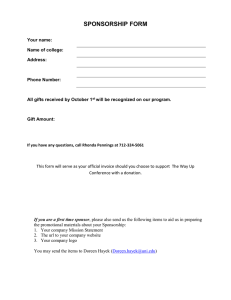

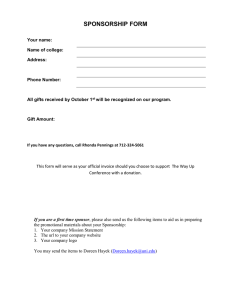

advertisement