Why Was It that Europeans Conquered the World? Philip T. Hoffman

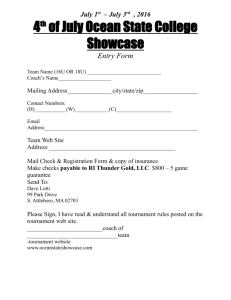

advertisement