Leading the Future of the Public Sector: The Third Transatlantic... University of Delaware, Newark, Delaware, USA

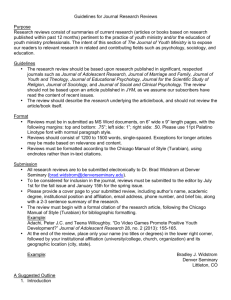

advertisement