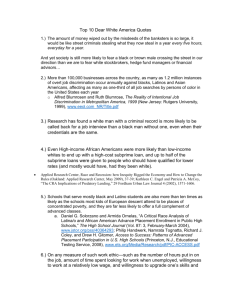

Race, Place and Poverty Revisited Michael A. Stoll, UCLA National Poverty Center Working Paper Series

advertisement