Document 13959533

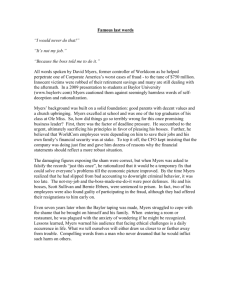

advertisement

[http://www.tampabay.com/news/humaninterest/world‐war‐ii‐vet‐sees‐self‐hypnosis‐as‐way‐to‐defeat‐ptsd/1179910] July 12, 2011 World War II vet sees self‐hypnosis as way to defeat PTSD By Justin George, Times Staff Writer Myers’ bottled up his World War II memories for years. After retirement, PTSD reared its head, putting him in a hospital. The 85‐year‐old man has a bad heart. He can't walk more than 10 steps. But Pat Myers has a message to share. So he wheels around his assisted living facility with a homemade sign on the back of his motorized chair: FREE CURE. Self‐hypnosis. That's his cure. Simple but effective, in his view. He wonders how life might have been different if someone had shared this with him after he returned from World War II, before all those years of suicide attempts, and shock therapy, and punching holes into walls. Like some of the soldiers who return home these days, Myers struggled with post‐traumatic stress disorder, fear and guilt stowed inside him for most of his life. Then, one night seven years ago, he read a self‐hypnosis book and recorded himself reading passages about draining negative emotions into an imaginary balloon that he would release forever. He envisioned it all in bed. One night changed everything, he says. He knows there are skeptics, including his own children. But even his kids can't deny something's different about him. He has a purpose. He remembers only bits of what happened in the Navy, like the time a suicide plane hit a ship in the South Pacific and killed several sailors. He should have been on the ship, but instead, was on sick leave. The man who replaced him died. Myers felt guilty, as if he had cheated death at someone else's expense. The seeds of mental illness took root. In 1944, he returned home to St. Mary, Mo., and never spoke of his experiences. He couldn't sleep for three months and tried drinking. But he found a coping method that suited him better. Pat Myers, in his assisted living facility in Lutz last week, experienced suicide attempts, counseling and shock therapy from post‐traumatic stress disorder. Then he hypnotized himself. He says he was a different man the next day. He became a workaholic, a salesman. He made enough money to put all five of his kids in private school. He was intense. Ultracompetitive. Driven. Feared. His son Steve remembers his father would stop in traffic if something was on his mind. He wanted it to be on everyone else's mind, too. His daughter Debbie McAuliffe remembers crouching low on the floorboard to be safe when her dad had a sudden flash of anger, punched the gas and hurtled through traffic. The salesman bought and sold houses over and over, forcing the family to move, and went through 45 cars like they were baseball cards. His children saw the cracks. But to Pat Myers, his breakdown was sudden, unexpected. In 1988, retired at the age of 62, Myers was with his wife, sitting on the water in Tampa. It was a calm day. But inside, he was boiling with anxiety. He told his wife to summon his daughter, who had grown up to be a psychiatric nurse. They sent him to Memorial Hospital, where he was committed for a month. For 15 years, he was treated for depression at the James A. Haley VA Medical Center. He thought about driving into a tree and killing himself. He rode his bike on the Gandy Bridge against traffic. He was committed six times. Doctors gave him shock therapy and prescribed drugs. He sat through group counseling sessions. A VA doctor finally suggested hypnosis. So Myers found a book, Self Hypnosis for a Better Life, by William W. Hewitt. It urged him to take deep breaths and focus on all the negative energy draining out of him. In his mind, he went to the beach, stuck his toes into warm sand and waded into an ocean of faith and courage. The book instructed him to forgive those who have wronged him and shut a door to the past, tossing the key into the waves. The next day, something strange happened. He watched a World War II program on television without getting upset or having to change the channel. Myers couldn't believe it. He watched another one, to test himself. He got through that one, too. He knew he couldn't keep this a secret. At the Lakeshore Villas Health Care Center in Lutz, the once‐strapping 6‐foot‐3 sailor requires constant blood pressure monitoring and is too weak for a pace maker. But he circulates the center in his wheelchair, evangelizing with instructional tapes and a portable cassette player. He said he's helped a Vietnam veteran. He's made his kids listen, too. "It halfway worked," said Steve Myers, now 56. "I pretty much challenge everything. Let me put it this way: I was surprised at the level of response I got." But he acknowledges a change in his dad. "It was night and day." His nurse daughter doesn't completely buy his methods. But she knows one thing: This mission has given her father a meaningful, positive focus — a "life's work." Pat Myers wants to talk to returning veterans, but he feels he lacks a stage. Every day, he reads the newspaper, looking for soldiers and trauma victims. He knows he may not have much longer to reach others. One day, he had his grandson put up a YouTube page called "PTSD: Your Exit Strategy." He sat near the edge of a bed and wore a suit. He looked into a camera and began: "I wish someone like me was there for me." Justin George can be reached at (813) 226‐3368 or jgeorge@sptimes.com.