Phonetics at Mountview Rick Lipton, Mountview Academy of Theatre Arts

PTLC2005 Rick Lipton & Matthew Reeve Phonetics at Mountview: 1

Phonetics at Mountview

Rick Lipton, Mountview Academy of Theatre Arts

Matthew Reeve, Mountview Academy of Theatre Arts

1. Background Research

Throughout all of the publicly funded drama schools in the UK, phonetics is a part of the curriculum. This tradition goes back to Elsie Fogerty and The Central School of

Speech and Drama at the Royal Albert Hall. In the early 1900's she liaised with

Daniel Jones and WA Akin to put the cutting edge studies of speech sound and resonance to use in voice training. She trained generations of teachers who then brought her curricula to drama schools. The National Council for Drama Training

(NCDT), the regulating body for public funding in drama training, has phonetics as a curriculum guideline for voice tuition in drama school. For the better part of a century, phonetics has been drilled into drama students generation after generation.

Why? How? What follows is a brief summary of the phonetic content of actor training and how phonetics is utilized at Mountview Academy of Theatre Arts.

When phonetics is discussed in the context of drama training by voice teachers, it usually refers to the phonetic symbols of the International Phonetics Association, and at a stretch, the phonemics of Pike (1947), Jones (1957), and others. The phoneme of phonemics is rooted in the principle of minimal pairs, with a catalogue of minimally contrastive units as the basis. At drama school, there was little discussion of allophones, or predictive variants of the phonemes, and little if any use of diacritics.

To become a voice teacher, one is either trained at the Central School of Speech and Drama's MA in Voice Studies (MAVS) Postgraduate Diploma in Voice Studies

(PGDVS), or Advanced Diploma in Voice Studies (ADVS), or one apprentices with a master teacher of voice, whether spoken or sung. On the course at Central, there is a phonetics class. It is phonemics. As of 1996-7, phonology was taught by a PhD candidate at UCL Phonetics. For the majority of training voice teachers, there was resentment at having to learn it. Speaking as an MA Phonetics graduate from UCL, there was nothing inaccurate or misguided about the phonology class. The issue was, from within the performance voice world, phonology had no apparent relevance.

The phonetics component, which was dictionary phonology, was also met with negativity. Why?

The challenge of uncovering this mystery was brought into focus after taking a job at

Mountview Academy of Theatre Arts, then Mountview Theatre School, in Wood

Green. The forum was teaching phonetics to six BA and three PG groups. It was

Mountview's second year of NCDT accreditation, and 'phonetics' was explicitly in the curriculum. Without anyone to give guidance, it was interpreted to be a class on the phonemics of RP, much like on the MAVS course at Central. There was also occasion to mention some specific detail about predictable positional variants.

Phonetics was a means to drill the students to iron out their RP. There was even a test at the end of the class. All these years later, do any of those early students use phonetics now? Probably not. Even then it seemed like a losing battle. That did not stop the determination to find a way to make phonetics more accessible and more relevant to training actors.

The MA in Voice Studies research to formally explore this is Phonetics in Actor

Training: Serving the Needs of the Professional Actor (Lipton 2001). It involves the interviewing of five dialect coaches, ten performers and ten students. The performers are performers in Saturday Night Fever , a show coached by Lipton in the

PTLC2005 Rick Lipton & Matthew Reeve Phonetics at Mountview: 2

West End, the students are Lipton's students from Mountview. The coaches are colleagues.

The first assumption is that coaches would advocate for phonetics. The findings are that each coach uses phonetics to inform her/his own personal practice, but did not use phonetics directly in her/his work. Most of accent tuition happens in situ, and the performers' own experience of the accent is the foundation from which the rest of the work comes. Most of the coaches said that phonetics can confuse performers, and gets them out of performance mode. The first assumption seems to be invalid.

The second assumption is that professional actors use phonetics. About two in ten in the study used phonetics, and much of it was cursory at best. One of the two who did use phonetics is a former student of Lipton. This assumption is also doubtful.

The third assumption is that the findings would support completely advocating the teaching and learning of phonetics for actors. After gathering the data, it seems that phonetics in its incarnation at that time lacks the necessary utility that actors need to perform. What actors really need is the ability to think phonetically, not the ability to use phonetic symbols. This is where the phonetics currently taught at Mountview begins. What do the students need to learn?

2. Phonetics in Drama School

Phonetics at Mountview is taught as an element of the Speech Class that forms part of the general voice curriculum. The Speech Class turns its focus to phonetics after examining the anatomy and physiology of speech production. This usually happens at the end of the first term and is integrated into the general focus on learning RP as a reference accent in the first year of study.

The objectives are to encourage students to identify underlying contrastive sounds in the individual's sound catalogue (phonemes), develop an understanding how these sounds are realized and how they manifest in connected speech. This detailed work provides vital 'ear training' for the student, allowing them listen to her/his own voices and the voices of others with 'new ears'. It becomes an important tool for approaching a role, making character choices about speech, accent, and the interpretation of text. This intellectual underpinning supports the students' practical work where they need to gain skills in appropriate articulation, RP, develop a facility to learn accents and deliver text in modes that reflect realistic current or recent historic patterns of speech.

Initial classes encourage the students to explore the diversity of speech sounds using The Craft of Speech (Lipton 2004). This is done through play and discussion.

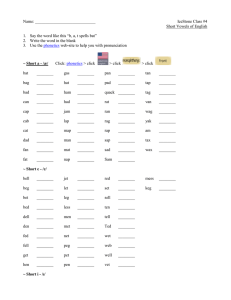

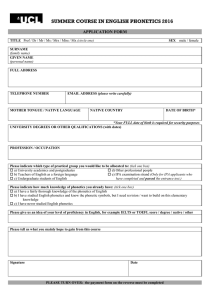

As part of these early classes games such as 'phonetics countdown' are played, where students are given a random array of phonemes that are sequenced into words. The learning experience can be enhanced by each student creating phoneme 'phonetic' placards for the game. The placards focus on a single phoneme by choosing a word that contains it, drawing a picture that includes the phoneme as a part of the illustration, writing the word orthographically and underlining where the sound is in the spelling. These pictures are often memorable and unwittingly the students acquaint themselves to the notions of 'sound systems' and 'lexical sets'

(Figure 1).

PTLC2005 Rick Lipton & Matthew Reeve Phonetics at Mountview: 3

Figure 1. A Sample Phonetic Placard

After the students have delineated the phonemes of English, attention can be drawn to the similarities and differences among them. They learn what a 'fricative' is, how a

'nasal' is formed and so on. This begins the process of the students understanding their own personal speech issues. The differences between their own accents and the accent of their peers are made apparent. Speech habits such as substitutions and omissions can be deconstructed. The students start to hear these details by themselves – and begin to realize the distance between their current level of articulation and the requisite level of speech for the stage. By the beginning of the second term, students have received a written personal voice agenda to pinpoint their accent and speech habits. This is based on their audition notes and an accent biography, which every student presents to peers in the first class of the year. The accent biography is an account of where the student has lived, where they have been educated, and any feedback received before coming on the course. The accent biography gives every student a tailored vocabulary to describe her/his speech habits. This enables students to compare notes and develop 'study buddies' to help address similar speech and voice training issues.

The second stage of phonetic training uses basic reverse transcription exercises and discussion of some of the phenomena that can occur in connected speech. At

Mountview the students are provided with a list of practice sentences. They contain indications of stress, assimilations of place and coalescence. There are instances of syllabic consonant formation, strong and weak forms, acceptable omissions and intraspeaker variation. The majority of students at Mountview have an accent other than RP. At first, when it comes to trying to sound like an RP speaker, they sound more like computer-generated speech. The reverse transcriptions attempt to illustrate the human side of this seemingly distant, formal dictionary speak.

The students will then move on to the basic transcription of short pieces of text in

RP. In the first instance, a sonnet by William Shakespeare is chosen for them. This exercise helps the student graphically illustrate the difference between the written and the spoken word. It is an introduction to iambic pentameter and making choices about the locations of stress within a thought. Completing the transcription the students further their knowledge of strong and weak forms and the various options within connected speech. The emphasis is not on right or wrong or on dictating rules; the phonetics are there to help visualise, explain and understand what the students already hear or feel. The students are encouraged to make their own

'informed' choices about their stage speech and to develop an ear for consistency. A key reference text in this exercise is the Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (Wells

2000).

Training actors need tools that can be taken away and used autonomously. The ability to understand, hear and, importantly, use lexical sets lies at the heart of the phonetic training at Mountview. No emphasis is placed on the phonetic symbol:

PTLC2005 Rick Lipton & Matthew Reeve Phonetics at Mountview: 4 although very useful for some students, the symbols can be counter-productive for others. As early as possible, students are encouraged to refer to the

FLEECE

vowel, for instance, to notice factors like her/his

STRUT

vowel sounds identical to her/his

FOOT vowel and so on. The use of lexical sets then speeds up the process of learning and understanding accents, that forms part of the curriculum in the second year of the students’ training. To support different learning modalities, the phonetic training is reinforced with visual representations of the phonetic symbols being discussed, aural repetitions of the sounds, and kinaesthetic, physical articulations. Through this experience of phonetics, the student is given awareness, a vocabulary, and an experience to be used during and beyond the training. Rather than teach actors to be phoneticians, they are taught to become phonetically aware.

REFERENCES

Jones, Daniel (1957). The History and Meaning of the Term “Phoneme”.

London:

International Phonetic Association.

Lipton, Richard (2001) Phonetics in Actor Training: Serving the Needs of the

Professional Actor . MA dissertation Central School of Speech and Drama.

Unpublished.

------(2004) The Craft of Speech . Unpublished.

Pike, Kenneth L. (1947). Phonemics . Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Wells, J.C (2000). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary . Essex: Pearson Education

Limited.