Business Case

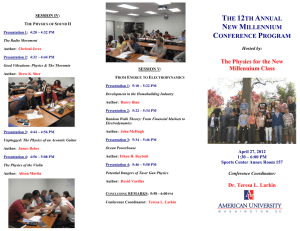

advertisement