What should an active causal learner value?

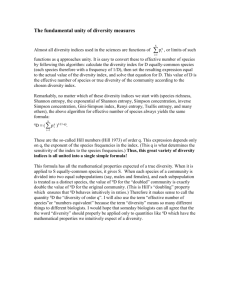

advertisement

What should an active causal learner value? 1 Bramley , 2 Nelson , 1 Speekenbrink , 3 Crupi , 1 Lagnado Neil R. Jonathan D. Maarten Vincenzo & David A. nrbramley@gmail.com, jonathan.d.nelson@gmail.com, m.speekenbrink@ucl.ac.uk, vincenzo.crupi@unito.it, d.lagnado@ucl.ac.uk 1 2 3 University College London Max Planck Institute for Human Development University of Turin Simulating many strategies in many environments Beyond Shannon: Generalized entropy landscapes Entropy is expected surprise across possible outcomes. Shannon entropy uses the normal P mean (e.g. x Surprise(x) × p(x)) as expectation and log(1/p(x)) for surprise. Different types of mean, and different types of surprise, can be used (Crupi and Tentori, 2014). SharmaMittal entropy (Nielsen and Nock, 2011) provides a unifying framework: P 1−β 1 ( i p(x)α) 1−α − 1 , where α > 0, α 6= 1, and β 6= 1 • Sharma-Mittal entropy: Hα,β (p) = 1−β • Renyi (1961) entropy if degree (β) = 1 • Learners based on 5 × 5 entropies in Sharma-mittal space α, β ∈ [1/10, 1/2, 1, 2, 10], plus our 5 weird and wonderful entropy functions. • Test cases: all 25 of the 3-variable causal graphs, through 8 sequentially chosen interventions. Repeated simulations 10 times each in 3 × 3 environments: 1. Spontaneous activation rates of [.2, .4, .6] 2. Causal powers of [.4, .6, .8] • Tsallis (1988) entropy if degree (β) = order (α) 0.35 • Error entropy (probability gain; Nelson et al. (2010)) if degree (β) = 2, order (α) = ∞ 5 =0 0.8 0.9 5 0.8 5 0.7 5 0.9 0.30 ● ● ● ● 0.10 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.3 0.6 0.4 0.4 0.2 0.5 p(x a=1/10 b=1/10 (Tsallis low) ● a=1/10, b=1 (Renyi low) a=10, b=10 (Tsallis high) ● a=10, b=1 (Renyi high) 0.2 0.4 0.4 0.25 ● 0.20 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Central kink ● Early kink Late kink 3 step ● 5 step ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 2) 2) 0.8 p(x 0.6 ● ● ● 0.2 0.6 ● ● 3) =0 p(x 3) =0 3) =0 3) p(x p(x 0.3 0.5 1 1 1 1 =0 3) 5 p(x 0.6 p(x1) = 0 p(x =0 0.6 =0 0.8 0.7 0.5 0.6 5 0.7 =0 p(x1) = 0 0.4 0.8 ● 0.15 =0 3) 0.6 0.2 5 p(x 0.3 0.5 0.4 5 5 0.2 0.4 0.3 0.1 5 5 5 5 0.9 0.8 2) 0.6 Probability correct =0 0.3 0.4 0.2 5 0.1 5 0.3 5 0.4 5 p(x 3) =0 p(x 3) =0 p(x 3) =0 p(x 3) =0 p(x 3) 1 Degree (β) 0.5 0.7 0.9 0 0.6 0.8 p(x p(x1) = 0 Shannon 1.2 ● ● 0.15 0.0 7 0.0 1 0.1 0.0 9 0.1 0.1 =0 0.6 0.7 0.5 0.6 0.6 p(x1) = 0 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.2 0.8 0.7 0.4 0.6 0.1 0.5 ● ● 0.9 1 0.3 0.5 Probability gain 0.7 0.25 9 p(x =0 2) 5 5 0.4 0.3 5 0.1 0.2 0.6 0.8 ● ● 0.10 0 3) = 0 p(x 3) = 0 p(x 3) = 0 p(x 3) = 0 3) = p(x 4 3 2 2) p(x p(x 0.8 =0 p(x 3) =0 p(x 0.8 0.6 0.8 p(x1) = 0 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 0 2 0.2 0.4 0.8 0.6 1 1 =0 p(x 1.6 0.8 0.8 1 • Shannon entropy achieves higher accuracy than probability gain p(x1) = 0 0.0 Ts a lli s p(x1) = 0 0.2 0.4 0.4 0.6 0.8 0.8 p(x1) = 0 0.6 1.4 1 0.2 1.2 0.8 0.6 0.6 1.2 0.8 0.4 0.6 0.4 0.8 p(x1) = 0 0.4 1.4 0.6 1.2 1 0.2 0.8 0.6 1.6 0.6 p(x1) = 0 0.0 ? 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 .1 1.0 .5 1 2 • many entropy functions achieve similar accuracy as Shannon entropy 10 Order (α) Probability of element N interventions performed 1.6 0.2 0.2 1.8 1.8 1.6 1.8 1.6 1.2 1 1.4 1.8 3) =0 p(x 3) =0 p(x 3) =0 3) p(x p(x 3) =0 1.4 1.8 =0 0.8 1.4 .1 2) 0.6 =0 =0 =0 1.2 p(x 0.4 2) 2) p(x 0.8 8 Results 0.2 0.6 p(x 0.4 0.4 1 6 p(x1) = 0 N interventions performed 0.8 1.6 4 0.2 1 0.4 0.6 0.6 0.4 p(x1) = 0 0.8 0.6 0.8 p(x1) = 0 0.2 1 0.8 0.4 0.6 0.8 p(x1) = 0 0.4 0.6 0.8 0.6 0.6 1 1.2 1.2 1 0.4 0.8 0.2 1.2 0.6 0.8 0.4 1.4 1.4 1.4 1.4 1.2 1 0.8 1.2 3) =0 3) p(x p(x 3) =0 p(x 3) =0 1 .5 1.4 0.4 Atomic surprise 1 0.2 0.4 0.3 p(x1) = 0 Renyi 0.6 2) Elementwise contribution to entropy 0.1 7 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 =0 ? 0.5 =0 1 0.5 p(x Posterior 0.4 2) 0.7 0.2 0.16 0.3 0.6 0.4 C p(x1) = 0 0.2 0.8 1 0.8 0.7 0.9 1 0.5 0.1 p(x 0.9 0.2 0.13 B Infinity 0.35 p(x1) = 0 0.5 0.09 C 0.5 1 2) Prior 0.06 B 5 0.5 0.3 0.03 C 0.0 5 0 B 0.4 0.5 =0 0.16 C B 0.1 0.3 5 0.2 5 0.1 1 0.7 2) C 0.45 0.4 0.4 p(x B C A 0.55 0.5 p(x1) = 0 =0 0.13 B A =0 0.4 0.3 0.5 2) 0.09 C A 0.6 0.65 0.9 p(x ? 5 p(x 0.06 B A 2) =0 0.03 C B A A p(x 2) C A 0.45 0.2 =0 B 0 ? 0.6 0.4 0.5 2) C A + ? 0.3 0.3 0.7 p(x A 0.4 0.65 p(x1) = 0 0.6 Generalised entropy C B 0.4 0.5 0.5 1 A C B Probability of element 0.6 0.4 0.3 C B 1.0 0.3 0.45 0.4 p(x1) = 0 =0 C B 0.8 C B A 0.6 0.6 2) C B C B A 0.4 A C B 0.2 0.55 0.5 0.5 0.4 0.45 p(x C B C B A A 0.0 0.65 p(x1) = 0 =0 B Example 2 + − C B C B A A A 0.5 0.6 0.55 0.5 C B 0.65 0.3 0.35 0.6 2) A 3. Observe the outcome ? A C B C B C B 0.5 0.55 0.65 A 0.2 0.25 0.4 0.45 0.8 ? Example 1 A C B C B C B A A 9 0.35 0.7 0.55 p(x ? A C B C B C B A A A 0 0.0 0.3 0.4 5 0.55 0.75 0.1 0.2 0.4 0.5 2 C B = 2) 0 9 0.0 0.3 0.5 1 − ? A C B C B A C B p(x1) = 0 1 ? ? A A C B C B A A C B 1 0.8 0.4 0.5 =0 1 1 ? C B A C B C B A C B 0.1 0.85 2) + A C B C B 1 0.9 p(x C C B 0.1 p(x A A + C B p(x = 2) 0 A B C B ● ● 0.95 5 0.4 C 0.11 p(x1) = 0 0.65 B p(x = 2) p(x A 0.1 A 0.11 =0 A 0.1 p(x1) = 0 2) A 0.09 0.11 0.11 p(x A A 0 A = 2) A p(x A 0.11 p(x1) = 0 =0 A 0.11 p(x1) = 0 2) 2. Choose an intervention 10 p(x 4. Update beliefs 0 ? = 2) ? Tsallis 0.1 Tsallis 0.5 Tsallis 1 (Shannon surprise) Tsallis 2 (Quadratic surprise) Tsallis 10 0.07 0.1 0.11 p(x ? 5. Repeat a=1, b=1 (Shannon) a=Inf, b=2 (Probability gain) 0.30 Generalised surprise values 'Bad' entropy simulations 0.35 Generalised entropy simulations 0.20 1. Reach into the system 0.05 • Intervening on a causal system provides important information about causal structure (Pearl, 2000; Sprites et al., 1993; Steyvers, 2003; Bramley et al., 2014) • Interventions render intervened-on variables independent of their normal causes: P (A|Do[B], C) 6= P (A|B, C) • Which interventions are useful depends on the prior and the hypothesis space • Goal: Maximize probability of identifying the correct graph Probability correct What is active causal learning? • but the interventions chosen vary widely: 1.0 Intervention choice type proportions (N = 18000) 'Bad' atomic surprise functions ● 0.7 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 1.0 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 Probability of element ● 0.1 0.18 0.3 0.22 0.2 0.8 0.1 0.1 0.4 0.9 0.2 4 0.1 4 2) 0.3 0.5 =0 0.8 =0 0.1 6 0.3 2) =0 8 0.1 =0 0.4 0.7 0.8 0.5 0.6 0.2 0.6 0.4 0.1 Sprites, P., Glymour, C., and Scheines, R. (1993). Causation, Prediction, and Search (Springer Lecture Notes in Statistics). MIT Press. (2nd edition, 2000), Cambridge, MA. 0.6 p(x 3) = p(x 3) = 0 0.2 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.6 0.2 p(x1) = 0 Three random steps 0.1 0.1 00.4 .5 0.7 0.9 0.8 0.1 4 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.8 0.1 0.4 0.2 Late kink 0.3 0.2 0.2 0.7 Early kink p(x1) = 0 .4 00.5 p(x1) = 0 0.3 0.1 0.14 0.8 0.16 0.2 0.24 0.2 .6 0.7 0 .4 0.5 0 0.14 0.28 0.3 0.18 0.3 0.26 0.22 0.9 Central kink 4 p(x1) = 0 8 0.1 0.5 0.1 Number of interventions performed 12 0.4 10 0.3 8 0.2 6 0.5 0.1 6 0.18 0.2 0.2 0.28 0.6 0 .7 0.4 0 .5 0.24 8 0.1 0.1 8 0.1 4 ● p(x 3) = 0 0.2 4 0 p(x 3) = 0 p(x 3) = 0.2 4 0 0.1 0.6 0 Renyi, A. (1961). On measures of entropy and information. In Fourth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, pages 547–561. p(x p(x 2) 2) p(x p(x =0 0.6 0.4 0.6 0.1 Number of interventions performed 0.2 0.2 0.1 2) 0.24 0.5 4 Five step 0.7 0.28 0.4 ● 0.2 0.6 0.26 0.3 2 Three step Pearl, J. (2000). Causality. Cambridge University Press (2nd edition), New York. 0.14 ● 0.24 12 Late kink Nielsen, F. and Nock, R. (2011). A closed-form expression for the sharma-mittal entropy of exponential families. arXiv preprint arXiv:1112.4221. 0.26 10 Early kink Nelson, J. D., McKenzie, C. R., Cottrell, G. W., and Sejnowski, T. J. (2010). Experience matters information acquisition optimizes probability gain. Psychological science, 21(7):960–969. ● ● 8 Central kink Crupi, V. and Tentori, K. (2014). State of the field: Measuring information and confirmation. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A, 47:81–90. 0.8 6 Renyi high Bramley, N. R., Lagnado, D. A., and Speekenbrink, M. (2014). Forgetful conservative scholars - how people learn causal structure through interventions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition, doi:10.1037/xlm0000061. 0.7 4 Tsallis high References Probability of element 0.9 2 Renyi low Csiszár, I. (2008). Axiomatic characterizations of information measures. Entropy, 10(3):261–273. ● ● Tsallis low • when are particular entropy functions cognitively plausible? 0.2 0.6 0.4 0.0 4 3 ● ● Shannon • which properties of entropy functions are important for particular situations? 0.0 5 0.4 ● ● ● p(x 0.2 ● ● 2 ● ● 1 0.6 ● ● Probability gain Information gain Random interventions Mean Shannon information gained 0.8 ● ● ● 0.0 Mean probability correct ● ● ● ● 0.2 Performance by simulated strategy 1.0 Performance by simulated strategy Atomic surprise Bramley et al. (2014), test performance learning all 25 of the 3-variable graphs in an environment with spontaneous activation rate p = .1 and causal power p = .8: Probability gain • in which instances do different strategies strongly contradict each other? Central kink Early kink Late kink Three step Five step 0.1 0.8 Elemental contribution to entropy Can information gain beat probability gain at probability gain? Human data Questions: 'Bad' elementwise entropies 1.0 Probability gain Choose intervention i ∈ I that maximises expected maximum probability φ in posterior over causal graphs G ∈ G P E[φ(G|i)] = o∈O φ(G|i, o)p(o|G, i) where φ(G|i, o) = maxg∈G p(g|i, o) Information gain Choose intervention that minimises expected Shannon entropy P P E[H(G|I)] = o∈O H(G|i, o)p(o|G, I) where − g∈G H(g|I, o) = p(g|I, o) log2 p(g|i, o) To further broaden the space of entropy functions considered, we first created a variety of atomic surprise functions. From these we derived corresponding entropy functions, always P defining entropy as x Surprise(x) × p(x). The resulting entropy functions vary in which entropy axioms (Csiszár, 2008) they satisfy. 0.0 Strategies for choosing interventions myopically 0.8 Weird and wonderful (bad) entropy functions Observation One−on One−on, one−off Two−on One−off Two−off 0.1 0.2 p(x1) = 0 Five random steps Steyvers, M. (2003). Inferring causal networks from observations and interventions. Cognitive Science, 27(3):453–489. Tsallis, C. (1988). Possible generalization of boltzmann-gibbs statistics. Journal of statistical physics, 52(1-2):479–487.