TOMATOES AND THE CLOSER ECONOMIC ... WITH AUSTRALIA R. L. Sheppard

advertisement

TOMATOES AND THE CLOSER ECONOMIC RELATIONSHIP

WITH AUSTRALIA

R. L. Sheppard

Views expressed in Agricultural Economics Research Unit Discussion Papers

are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the

Director, other members of the staff, or members of the Policy or Advisory

Committee.

Discussion Paper No. 75

Agricultural Economics Research Unit

Lincoln College

Canterbury

New Zealand

November 1983

ISSN 0110-7720

THE AGRICULTURAL ECONO/'v1TCS RES.EARCH UNiT

Lincoln College, Canterbury, N.Z.

The Agricultural Economics Research Unit (AERU) was est3.blished in 1962 at Lincoln

College, University of Canterbury. The aims of the Unit arc LO assist bywayof economic

rcst:arch those groups involved in the many aspects ofNe',;;,' Zealand primary production

and product processing, distribution ;lnd n1<lrketing.

Major sources of funding have be.en annual grants from the Department of Scientific

and Industrial Research and the College. However, a substantial proportion of the

Unit's budget is derived from specific project research under contract to government

departments, producer boards, farmer organisations and LO commercial and industrial

groups.

The Unit is involved in a wide spectrum of agricultural economics and management

research, wi.th some concentration on production economics, naturai resource

tconomics, mHketing, processing and transportation. The results of research projects

rire published as Research Reports or Discussion Papers. (For further information

regarding the Unit's publications seethe inside back cover). The Unit also sponsors

periodic conferences and seminars on topics of regional and national interest, often in

conjunction with other organisation~.

. •.

The Unit is gUIded in policy formation hy an Advisqry Committee first established in

:982.

The AERU,the Department of Agricultural Economics and Mar\<:eting, and the

Department of Farm Management and Rural Valuation maintain a close working

relationship on research and associated matters.'fhe heads of these two Departments

He represented on the Advisory Cornrilittee, and together with the Director, constitute

in AERU PoHcy Committee.

.

UNIT ADVISORY COMlvIITTEE

G:W. Butler, M.Sc., Fi1;dr., F.R.S,N.Z.

(Assistant Director-General, Department of Scientific & Industrial Research)

B.D. Chamberlin

(Junior Vke-President, FederatedF?smers of New Zeilland Inc.)

F.D. Chudleigh, B.Sc.(Hons), Ph.D.

(Director, Agricultural Economics Research Unit, Lincoln College) {ex officio}

]. Clarke, -C.M~G.

(Member, Ne",. Zealand Planning C01Jn.ciJ)

J.B. Dent, 13.Sc.; M.Agr.Sc., Ph.D.

(}~:;-of::~sor & He£l.d of Departl-.nent of FarDJ. IviB.nagement & Rural v~~ju~..tion, Liricoin. Col1.ege)

E.J. Neilson, B.A.,B.Corh., F.eA., F.c.I.S.

(Lincoln Colkge Council)

B.]. Ross, M,Agr.Sc.,

(P'_ofessc,) & Head of Department of AgriccltlJ1'al Economics & Marketing, Lincoln ColJege}

P. Shirtcliffe, :S.Com., AeA

(I,Iorninee of Advis.Qry Committee)

Professor SirJ?iil.CS Stewart, M.A., Ph.D.,b~p. V,F.M., FNZIAS, FNZSFM

(Principd of Lincoln College)

E,J, Stonyer, B.Agr. Sc.

(Director, ECO;lomics Division, Ministry of Agl,'i<:uIture and Fisheries)

UNIT RESEARCH STAFF: 1983

Director

P.D. Chudleigh, B;Sc. (Hons), Ph.D.

Re.llltlrchFeli(Nu i1l Agrialltural Pollc.v

J.G. Pryde, O.B.E., M.A., F.N.Z,LM.

Senior Researc,~ Economists

A.C. Beck, B'sc.Agr., M.Ec.

KL. Leathers, B.S" M.S., Ph.D.

RD. Lough,RAgLSc.

R.L Sheppard, B;Agr.Sc.(Hons). B.B.S.

Research Economist

R:G. Moffitt, B.Hort.Sc., T-J.D.H.

il.ssi.rtant ReJeearrh 'EcoflomiJts

G. Greer, B.Agr.Sc.(Hons) (D.S.I.R SecQndment)

SA Hughes, B.Sc.(Hons), D.RA.

G.N. Kerr, B.A., M.A. (Hons)

M.T. Laing, B.Com.(Agr), M.Com.(Agr) (Hons)

P.J. McCartin, R Agr.eom:

P.R. McCrea,B.C6m. (Agr)

J.P. Rathbun, B,Sc., M.Com.(Hons)

Post Graduate Fellows

N. Blyth, B.Sc.(Hons)

c.rz.G. D,nkey, B.Sc., M.Sc.

Secretary

C.T. Hill

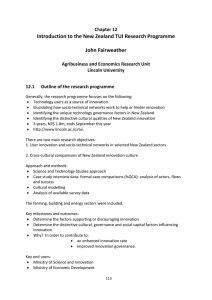

CON TEN T S

Page

LIST OF TABLES

( iii)

LIST OF FIGURES

(iii)

PREFACE

(v)

(vii)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

(ix)

SUMMARY

SECTION

SECTION 2

SECTION 3

SECTION 4

INTRODUCTION

I. I

CER Negotiations

1.2

CER Negotiations - Tomatoes

AUSTRALIAN TOMATO SUPPLY POTENTIAL

5

2. I

Introduction

5

2.2

Australian Tomato Supply

5

2.3

Queensland Production

5

2.4

Queensland Production Costs

6

2.5

Required New Zealand Returns

6

2.6

Queensland Fruit Fly

7

2.7

The Queensland Market

7

NEW ZEALAND TOMATO PRODUCTION AND PRICES

II

3. I

Introduction

II

3.2

Production Costs

12

3.3

Product Supply and Market Prices

14

THE POSSIBLE AUSTRALIAN SUPPLY IMPACT

19

REFERENCES

APPENDIX

2

23

Tomato Production Costs - Queensland

25

LIST OF TABLES

Table

Page

Australian Fresh Vegetable and Tomato Access to New Zealand

under CER

3

2

Monthly Average Tomato Prices - Brisbane Wholesale Market

8

3

Monthly Tomato Throughput - Brisbane Wholesale Market

9

4

New Zealand Tomato Production

11

5

Auckland Region Production Parameters 1981/82

13

6

Tomato Supply and Price at Auction 1982

15

7

Average Monthly New Zealand Tomato Prices at Auction

16

8

Access for Australian Tomatoes -Quantity

20

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure

2

Page

Monthly Tomato Prices and Throughput - Brisbane Wholesale

Market

10

Average Monthly New Zealand Tomato Prices

17

(iii)

PREFACE

The Closer Economic Relationship (CER) with Australia has evoked both optimistic

and pessimistic views on the impact on New Zealand manufacturing industries.

Views regarding the impact on the New Zealand agricultural and horticultural

sectors have been less well vented.

An exception has been in the glasshouse tomato industry where considerable

fears are held regarding the effect of the access given to Australian tomato

growers on the viability of New Zealand producers.

This paper presents information on the CER agreement and data on costs

and supply from both Australia and New Zealand. The paper concludes that the

impact of the CER agreement on the New Zealand industry is likely to be small,

at least for the next five years.

P D Chudleigh

Director

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research reported upon in this Discussion Paper was undertaken while

the author was on a period of Australian Conference Leave from Lincoln College.

The financial assistance of Lincoln College which enabled the research to

be undertaken following conference attendance in Brisbane is acknowledged.

The financial assistance received from the New Zealand Institute of

Agricultural Science through the Westpac Travel Award for 1982/83 is also

gratefully acknowledged.

(vii)

SUMMARY

The Closer Economic Relationship with Australia agreement (CER) was brought

into effect on I January 1983. The CER provided for the liberalisation of trade

between New Zealand and Australia. This liberalisation is to be effected

through the gradual elimination of barriers to trade following an established

formula. Some departures from the formula are provided for where specific

products would be treated in an inappropriate manner if the formula were followed.

The objective of the liberalisation procedure is complete removal of barriers

to trade by 1995.

The granting of access to the New Zealand market for Australian tomatoes

is included in the agreement. The level of access provided caused New Zealand

growers of hothouse tomatoes to express concern over the possible impact of

imports on the New Zealand industry. This Discussion Paper provides a report

on an investigation of the likely impact of Australian tomato supplies on the

New Zealand market. It is established that the most probable source of exports

to New Zealand is Queensland. A review of Queensland tomato production costs

indicates that a price of $A5.00/10 kg carton would be required by Queensland

growers to cover their variable production costs. Additional costs involved

in exporting to New Zealand result in a New Zealand market price of $NZI7.00/

10 kg carton ($NZI.70/kg) being required by Queensland growers. This price

can be achieved on the New Zealand market between June and November. Exporting

to New Zealand would therefore only be attractive to Queensland growers during

that period.

The New Zealand hothouse tomato growing industry supplies approximately two

thirds of the tomatoes for the freshmarket. These supplies are predominantly

during autumn, winter and spring when higher prices are available. During

summer, prices are lower as outdoor grown- tomatoes become available. The

hothouse tomato growing industry considers that the high winter prices are

essential to their profitability. It is probable that some price reductions

will occur as a result of imports from Australia being available during winter.

However, the quality of the Australian product is likely to be inferior to

that available in New Zealand and therefore the price impact will be less.

In addition, up to 1988 the quantity of tomatoes able to be imported from

Australia is limited to a level equivalent to between 0.57 per cent and 1.01

per cent of average New Zealand annual hothouse tomato production. The

average variation in New Zealand hothouse tomato production from year to year

(over 1975 to 1981) exceeded the total allowable Australian supply by between

14 and 25 times. Therefore the impact of New Zealand supply variations on

the market price is likely to be greater than the impact of supplies from

Australia.

Over the longer term, increased supplies from Australia can be expected

to have a greater impact on the New Zealand market. The establishment of

appropriate premiums for higher quality New Zealand tomatoes through the use

of an effective marketing system would reduce this price lowering effect of

imports from Australia. Some reduction in New Zealand hothouse tomato production

could be expected as less efficient growers fail to achieve adequate returns.

There is likely to be increased total demand for tomatoes during the winter

period when lower priced Australian tomatoes are available. Increased outdoor

tomato production during the summer months could also be expected to offset

reduced hothouse tomato supplies during summer. Overall, prices are likely

to be reduced (with premiums available for high quality product) and tomato

consumption could be expected to increase.

(ix)

SECTION 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1

CER Negotiations

The Closer Economic Relationship with Australia agreement (CER) emerged

as a concept during 1979. Following the annual NAFTA (New Zealand/Australia

Free Trade Agreement) Ministerial meeting in April 1979, the Australian and

New Zealand Prime Ministers requested senior officials in both Governments

to examine ways of achieving closer economic co-operation between the two

countries. In March 1980, the Australian Prime Minister visited New Zealand

and a communique was issued from the meeting of the two Prime Ministers that

established the framework for examination of possible arrangements for a closer

economic relationship. Negotiations continued between Australian and New

Zealand Government Ministers and officials, including extensive discussions

between Government officials and industry sector representatives in both

countries, during 1980 and 1981 culminating in a meeting between the New

Zealand Prime Minister (and other New Zealand Ministers) and the Australian

Deputy Prime Minister from 20-21 April 1982. This meeting finalised the

major content of the agreement that was brought into effect from 1 January 1983.

The New Zealand Prime Minister, in his Press Statement of 4 June 1982,

outlined the CER agreement as "a comprehensive agreement covering trade and

aspects of economic relations with our most important trading partner. It

is broad in scope and open-ended in duration although it is proposed that

there will be a major review of the arrangements after five years to examine

whether adjustments are needed to ensure that they are bringing benefits to

both countries on a reasonably equitable basis."

The objectives of the CER Agreement are:

"

(i)

to strengthen the broader relationship between Australia

and New Zealand;

(ii)

to develop closer economic relations between the Member

States through a mutually beneficial expansion of free

trade between New Zealand and Australia;

(iii)

(iv)

to eliminate barriers to trade between Australia and

New Zealand in a gradual and progressive manner under

an agreed timetable and with a minimum of disruption;

and

to develop trade between New Zealand and Australia under

conditions of fair competition." (CER, 1983)

The overall direction taken by the agreement is to liberalise trade

between the two countries. In New Zealand, this involves a removal of import

licencing for Australian goods, tariff reductions and removal of export

incentives for goods exported to Australia. Movement toward trade liberalisation has been tied to a formula in the agreement which involves a steady

reduction in trade barriers with the ultimate objective of complete liberalisation in 1995. Some special provisions have been established for particular

products outside the general formula.

1.

2.

1.2

CER Negotiations - Tomatoes

During the Closer Economic Relationship negotiations between Australia

and New Zealand, proposals were put forward regarding the levels of access

available for different classes of products. The CER access formula for

the fresh and chilled vegetable area was for access for Australia to New

Zealand of a total annual value of $NZ200,000 in the first year of CER.

Within this overall level, tomatoes were set at 10 per cent of the total,

an initial import value of $NZ20,000. These proposals had received favourable

consideration by the New Zealand tomato growing industry.

As CER negotiations proceeded, it became apparent that some changes in

the general access formulae for Australian goods to New Zealand would be

required in order to ensure the finalisation of a CER agreement. It was

therefore agreed (in association with a number of other changes for a range

of products) that the minimum base access level of $NZ200,000 CIF for fresh

and chilled vegetables would be increased to $NZ400,000 CIF. Within this

access level for fresh and chilled vegetables it was further agreed that the

initial access level of $NZ20,000 for tomatoes was not commercially viable.

Therefore the provision for tomatoes was increased from $NZ20,000 to NZ$ISO,OOO.

This access level for tomatoes was agreed to by the New Zealand Government

subject to agreement being reached on a suitable and acceptable method of

minimising the impact of imports of Australian tomatoes on the New Zealand

market. Negotiations on this aspect between the New Zealand Vegetable and

Produce Growers' Federation and the Queensland Committee of Direction of

Fruit Marketing (C.O.D.) in association with the Australian Commonwealth

Department of Primary Industry took place during November/December 1982.

As no agreement was reached in these negotiations, further discussions were

held between Government officials of both countries in December 1982.

These discussions resulted in an import procedure for Australian tomatoes

being established for the first 18 months licencing period from I January 1983

to 30 June 1984, under which 100 per cent of the EAL'slwill be allocated

to Fruit Distributors Ltd (FDL)2 who will act as a sole importer during that

period. Prior to 30 June 1984, consultations will take place between the

2

Exclusive Australian Licences

Fruit Distributors Ltd (FDL) is an unlisted public company, established

at the request of Government on I January 19SI. It was established to

import and distribute citrus fruits, bananas and pineapples in New Zealand.

Fresh grapes were included in 1961. At present there are 39 shareholder

companies which operate in the wholesale fruit and produce business. The

obligations imposed on FDL by Government are:

"(a)

To import adequate supplies of fresh citrus fruits, bananas, pineapples and grapes and to distribute these equitably throughout the

country at reasonable prices.

(b)

To encourage the development of the fruit business in certain

Pacific Island nations.

(c)

To accord a reasonable measure of protection to the citrus fruit

and fresh grape growing industries in New Zealand.

In return for meeting this obligations, the company has the sole right to

import bananas, citrus fruits, pineapples and grapes." (Fruit Distributors

Ltd, 1981).

3.

industries and officials of New Zealand and Australia to consider whether

FDL will remain the sole importer beyond 30 June 1984. In the absence of

an agreement for FDL to continue as the sole importer, EAL's will be allocated

in each licencing year from I July 1984 to 30 June 1988 on the basis that

not less than 40 per cent is allocated by open tender. A review of the allocation of EAL's will be undertaken in 1988. In addition (where agreement

regarding FDL is not reached), EAL's applicable from the licencing year I July

1984 will be tagged as being required to be used as follows: 50 per cent in the

period I July to 30 December and 50 per cent in the period I January to 30 June.

This agreement results in the level of access shown in Table 1 where real

(after inflation) increases from year to year of 15 per cent have been included

plus an allowance of 10 per cent for inflation: it should be noted that the

initial access at $NZ400,000 for fresh vegetables is for a twelve month period

based on a June year. The agreement did not come into effect until I January

1983 therefore only half of that initial access is available in the first June

year.

TABLE I

Australian Fresh Vegetable and Tomato Access to New Zealand under CER

a

Tomatoes

07.5% of

Fresh Vegetables)

Total Fresh

Vegetables

January 1983

July 1983 to

July 1984 to

July 1985 to

July 1986 to

July 1987 to

a

b

to

30

30

30

30

30

30 June 1983

June 1984

June 1985

June 1986

June 1987

June 1988

200'00~1 706 OOOb

506,000

640,090

809,714

1,024,288

1,295,724

'

75,000} 264 750 b

189,750

'

240,034

303,643

384,108

485,897

Tomatoes are included in the "Total Fresh Vegetables" access.

The Exclusive Australian Licence for I January 1983 to 30 June 1984 will

be issued as one block for $706,000 for fresh vegetables, including $264,750

for tomatoes.

The New Zealand Vegetable and Produce Growers' Federation has indicated

that it believes imports would only occur during the period of relatively

higher prices for tomatoes on the New Zealand market (during the New Zealand

winter months) and this would lower prices at that time. The effect of this,

according to the New Zealand Federation, would be the loss of adequate income

for the New Zealand glasshouse industry and the loss of New Zealand based

tomato supply. It was further considered that the loss of the hothouse tomato

supply for New Zealand would result in imports from Australia over the total

year at a higher average cost than was available from the New Zealand industry.

(This was based on the assumption that almost all fresh tomatoes for the New

Zealand market were grown in hothouses. However, only approximately 65 per

cent of fresh market supplies are hothouse sourced (Table 4).)

4.

The level of controversy apparent in the situation indicated a need for

an objective study of the likely impact on the New Zealand tomato industry of

imports of Australian tomatoes. Section 2 of this report presents the findings

from the review of the Australian tomato growing industry, Section 3 presents

information on the New Zealand glasshouse tomato production system and Section 4

of the report presents some conclusions regarding the likely impact of Australian

tomato supplies.

SECTION 2

AUSTRALIAN TOMATO SUPPLY POTENTIAL

2.1

Introduction.

A review of the potential for tomato imports to New Zealand from Australia

was undertaken during a visit by the author to Australia in February 1983. The

review involved an examination of the basis of tomato production in Australia

(i.e. indoor vs outdoor, importance of supply regions) and the costs involved

in tomato production. From this information, an assessment of the most likely

supply areas, the potential of those areas to supply tomatoes to New Zealand

and the required returns in New Zealand could be undertaken. Where a potential

for tomato supply from Australia could be identified, the required returns

could be compared with the New Zealand tomato prices (prior to imports) and

the possible impact of Australian tomato supply assessed.

2.2

Australian Tomato Supply

The Australian fresh tomato market is based primarily upon the ability

of the Queensland area to grow tomatoes under field conditions for a large

portion of the year. This has meant that the Queensland industry has developed

to a point where it supplie.s a major proportion of the total fresh market

for tomatoes in the Eastern and South-eastern part of Australia. The development has resulted in the virtual elimination of glasshouse grown tomato supply

in New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia. The development of the

Queensland industry has largely been a result of the development of the variety

of tomato called "Floradade". This tomato is bigger than that normally grown

in New Zealand, has a firm texture, a strong skin and is therefore able to

withstand considerable post harvest treatment, transport and storage. A

shelf life for this product in excess of two weeks is· accepted.

In view of this situation, the investigation of the Australian tomato

growing industry has been limited to a review of the Queensland situation

as it is unlikely that significant supplies of tomatoes to New Zealand will

come from any other area of Australia.

2.3

Queensland Production

In 1980-81, total Queensland production of tomatoes was 55,660 tonnes.

This represented approximately 20 per cent of total Australian tomato production, but in excess of 70 per cent (author's estimate) of Australian production

of fresh market tomatoes. Queensland tomato production has been increasing

steadily with 1980-81 production representing an increase of 80 per cent over

the 1975-76 production level. The area planted to tomatoes has increased

from 2,400 to 3,400 hectares over the same period. Also, tomatoes are the

most valuable vegetable crop in Queensland being worth an estimated $A37

million in 1980-81. Since 1980-81, production in the Bundaberg region has

continued to increase dramatically as the transfer from sugar cane growing

to other forms of land use has occurred.

In the Northern growing area around Bowen, which is the major production

area, the harvest time is spread from May to November with peak production

occurring from July to October. In the Bundaberg district there are two

5.

6.

distinct peaks of production, in June and early July and in October/November.

In the southern parts of Queensland, the main harvest period is from December

to March. Therefore, the northern regions of Queensland have a supply period

which is predominantly within the winter months. The ability of Queensland

to supply tomatoes over the temperate climate winter period is of significance

to the New Zealand supply situation in view of the CER agreement.

2.4

Queensland Production Costs

In the Bowen area of Queensland, the variable production cost per 10 kg

carton of tomatoes is estimated to be $A4.80 as at January 1983 (Appendix),

This cost is assessed as the variable cost associated with the placing of

the product in the Brisbane market. In the Bundaberg district the variable

cost per 10 kg carton has been assessed at $A4.91 as at January 1983 (Appendix).

The equivalent cost for the south-east Queensland region has been estimated

at approximately $A4.8s per carton (Appendix). These costs represent in

January 1983 dollars the cost of production during the peak of the season for

each district. Therefore, it would appear to be appropriate to assume a

variable cost for Queensland tomato production at around $As.OO per 10 kg

carton for the 1983 production season (representing an average for all districts).

As this is an estimate of the average production cost, there will be

considerable variation around this level. Where production is undertaken

on a family basis, it is common for the cost of production to not include

a return to the family labour. For production from larger enterprises, the

inclusion of higher labour costs will mean a higher recognised specific

production cost.

2.5

Required New Zealand Returns

In order for a long term commitment to be made to the New Zealand market,

it would be necessary for Queensland growers to be able to achieve a return

of approximately $A 5.00 per 10 kg carton at a point equivalent to the Brisbane

market. In order to achieve this, the New Zealand price would need to cover

the transport to New Zealand plus the Queensland production cost and handling

costs. At present, the airfreight rate for the transport of tomatoes to New

Zealand is $AO.70 per kg, or $A7.00 per 10 kg carton. Additional handling

costs of $AI.OO could be expected to be incurred. Therefore a total return

on the New Zealand market of $AI3.00 would be necessary. At an exchange rate

of $NZI.33 per $AI.OO, a New Zealand market price of at least $NZI7.00 per

10 kg carton would be required.

If it was possible to transport tomatoes to New Zealand by sea, the

freight component would be reduced from $A7.00 per carton to $A3.00 and

this would result in the reduction of the required New Zealand price to

approximately $NZI2.00 per carton. The period required for the transport

of tomatoes by sea from Australia to New Zealand, including time for arrival

at the Australian wharf and delivery from the New Zealand wharf to the New

Zealand market, is approximately 7 days. The variety of tomato grown in

Queensland (Floradade) would probably withstand this period of transport

without undue deterioration. However, the uncertain nature of trans-Tasman

shipping arrangements and the necessity for the product to be guaranteed

delivery within the specified time, would probably act to inhibit movement

of tomatoes by sea. The availability of lucrative markets within Australia

would counteract the usefulness of the New Zealand market given the uncertainties associated with sea transport. Therefore, it is likely that only

tomatoes transported by air would become available in the New Zealand market.

7.

2.6

Queensland Fruit Fly

Imports of fruit and vegetables from the Queensland area are at present

banned by the New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries on plant health

grounds. This ban is imposed because of the danger of introducing Queensland

fruit fly into New Zealand. Tomatoes are not able to be fumigated as they

cannot withstand the treatment and therefore an alternative treatment method

will need to be established before imports of tomatoes can occur. Investigations are presently underway in Queensland to develop such a treatment.

Present research indicates that a 3 minute dip in a solution of Dimethoate

at a concentration of 425 mg per litre provides an adequate kill of fruit fly.

This form of treatment has recently been accepted by the Victorian state

authorities in Australia. Correspondence between the Australian Health

Department and the New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries would

indicate that it is probable that New Zealand will accept a similar treatment.

However, it is likely that the negotiations on the treatment will be protracted

given the importance of the inhibition of fruit fly arrival in New Zealand

and the likely pressure that will be brought upon the New Zealand authorities

by the agricultural/horticultural industry in New Zealand.

2.7

The Queensland Market

With an annual production level in excess of 55,000 tonnes and significant

increases in tomato production occurring it is apparent that the Queensland

tomato growing industry has a considerable potential to supply tomatoes to

New Zealand. Such supply would be dependent upon the achievement of an acceptable return to Queensland growers. It would appear that a price level of

approximately $NZI7.00 per 10 kg carton would be required in the New Zealand

market before supply from Queensland would be an economic proposition. This

assessment assumes that the supply of tomatoes from Queensland to New Zealand

would be undertaken on a continuing basis and therefore would be required to

provide a return which offsets at least the variable production and marketing costs incurred by Queensland growers. However, if prices available in the

Australian market fall to levels lower than the variable cost of production and

marketing, it is probable that Queensland growers would consider supply to

New Zealand where the return from the New Zealand market exceeded the returns

available in Australia. During 1982, the average price on the Brisbane wholesale market fell below $A5.00 per 10 kg carton during June, July, August and

December. This would imply that during those months there exists a potential

for supply to New Zealand at prices lower than the variable cost of production

and marketing.

A further factor that must be considered is the degree of supply and

price variability that exists on the Australian market. As an indication

of this, Tables 2 and 3 present the monthly average prices for coloured

tomatoes and the monthly throughput on the Brisbane Wholesale Market. This

information is also shown in Figure I.

Prices on the Brisbane Wholesale Market (Table 2 and Figure I) indicate

a constant general price level from 1978 to 1982 with substantial fluctuation

around this level. In real terms (after inflation) prices have declined

over the period. The fluctuations in price have some relationship with the

movements in throughput quantities with higher prices being related to lower

throughputs.

Over the period (1978-82), the monthly market throughput has tended to

increase from around 1,450 tonnes per month in 1978 to approximately 2,100

tonnes per month in 1982. This increase in throughput (approximately 45 per

cent) reflects the increased Queensland tomato production and is reflected

in declining real prices (after inflation).

8.

TABLE 2

Monthly Average Tomato Prices Brisbane Wholesale Market

Tomatoes - Coloured a

($A/I0 kg carton)

1978

1979

1980

1981

1982

January

5.55

5.00

13.52

6.39

6.84

February

6.27

5.21

6.65

8.75

5.04

March

7.85

5.20

8.50

9.91

6.07

April

9.06

3.43

7.83

12.37

5.72

May

II. 59

3.76

5.90

10.80

5.37

June

7.38

3.41

4.43

8.06

4.76

July

4.49

3.73

4.71

6.07

3.90

August

4.92

3.05

7.37

12.61

4.70

September

8.78

4.70

9.16

8.53

11.58

October

8.07

5.25

5.13

6.57

6.57

November

7.53

5.02

4.24

7.88

5.68

December

6.90

10.47

6.27

10.53

3.82

Annual Average

7.35

4.79

6.80

8.91

5.82

a

Green tomatoes are also sold through the Brisbane Wholesale Market. Supplies

have diminished in importance, however, and in 1982 a marked price difference

between coloured and green tomatoes only existed in January, February, April

and May when green tomato prices were approximately 20 per cent below coloured

tomato prices.

Source: Prices and Market Throughput on the Brisbane Wholesale Market,

Rocklea; Queensland DPI, Marketing Services Branch, February 1983.

9.

TABLE 3

Monthly Tomato ThroughputBrisbane Wholesale Market

(tonnes)

1978

1979

1980

1981

1982

January

1276

1972

1782

1717

1815

February

1432

1667

1658

1651

1923

March

1714

1695

1755

1712

2564

April

1352

1749

2068

2056

2034

May

1396

2111

1657

1429

1825

June

1063

1487

1386

1469

2129

July

1195

1523

1668

1994

1731

August

1616

2106

1421

1363

1678

September

1364

1950

1759

2356

2268

October

1251

2735

2485

1911

2103

November

2055

1972

2142

1710

2150

December

1886

1487

1905

2583

2820

17600

22454

21686

21951

25040

Total

Source: Prices and Market Throughput on the Brisbane Wholesale Market,

Rocklea; Queensland DPI, Marketing Services Branch, February 1983

The highest monthly average price achieved on the Brisbane Wholesale

Market between 1978 and 1982 was $AI3.52 per 10 kg carton in January 1980.

This is equivalent to $NZ1.80/kg. Over the June to November period (when

N.Z. prices are highest), the highest monthly average price on the Brisbane

Wholesale Market was $AI2.61 per 10 kg carton in August 1981. This is equivalent to $NZ1.68/kg. (The lowest price on the New Zealand market between 1980

and 1982 for the June to November period was $1.60/kg ~n June 1981 (Table 7).)

It would therefore appear that even though there is considerable price

variability on the Brisbane Wholesale Market the general level of prices

has remained relatively constant (a decline in real terms). Even when prices

have peaked, the level is equal to or lower than New Zealand seasonal peak

prices. Increasing Queensland production will probably tend to restrict real

price increases On the Brisbane Wholesale Market, if not lead to a further

reduction.

In order to assess the potential for Queensland to supply tomatoes to

New Zealand, it rema~ns to examine the New Zealand industry in terms of its

production, the cost of that production and the prices achieved on the New

Zealand market. Comparisons between the New Zealand return and that required

by Australian producers (given their own market situation) can then be made

and an assessment of the potential impact provided.

FIGURE I

o

Monthly Tomato Prices and Throughput ~.

Tomato Price

~

Market Throughput

Brisbane Wholesale Market

(Actual Prices)

14

Price

$A/IOkg

Carton

12

10

8

6

4

2

o

3000

~

2600

2200

1800

1400

J F M A M J J

1978

A S 0 'N D

J F M A M J J A SON D J F

1979

M A M J

.. ':r

~~~~~~~

J A SON D J F M A M J J

1980

1981

A SON D J

F M A M J

J A SON

1982

D

1000

Market

Throughput

(tonnes)

SECTION 3

NEW ZEALAND TOMATO PRODUCTION AND PRICES

3. I

Introduction

The New Zealand fresh tomato market is predominantly supplied by tomatoes

from the hothouse industry with approximately two thirds of the fresh market

tomatoes coming from this source. However, fresh market tomatoes constitute

only approximately 50 per cent of total tomato production (Table 4).

TABLE 4

New Zealand Tomato Production

(a)

Volume (tonnes)

Freshmarket

Year

Processing

(Outdoor)

Total

Outdoor

Hothouse

Total

1975

8984

15534

24518

25709

50227

1976

8383

19060

27443

19779

47222

1977

6025

21055

27080

33819

60899

1978

9992

14864

24856

31935

56791

1979

8271

15618

23889

1930 I

43190

1980

9528

18306

27834

29454

57288

1981

9523

8672

18266

27789

20185

47974

17529

26201

25740

51941

Average

(b)

Proportion from Each Source (%)

Year

% of total

% of total freshmarket

1975

36.6

63.4

48.4

51.2

1976

30.5

69.5

58. I

41.9

1977

22.2

77 .8

44.5

55.5

1978

40.2

59.8

43.8

56.2

1979

34.6

65.4

55.3

44.7

1980

34.2

65.8

48.6

51.4

1981

34.3

65.7

57.9

42. I

Average

33. I

66.9

50.4

49.6

Source: New Zealand Horticulture Statistics 1983, Economics Division, Ministry

of Agriculture and Fisheries, Wellington.

II.

12.

It is apparent from the supply information that a considerable degree of

annual variation occurs in the level of hothouse tomato supply. Over the

seven year period (Table 4), this annual variation averaged 2532 tonnes or

14.4 per cent of the average annual supply for the period. Total average

annual freshmarket supply variation was 1745 tonnes or 6.7 per cent of average

annual supply, indicating that outdoor tomato production tended to move in the

opposite direction to hothouse production. This indicates a degree of substitutability between the two types of production.

The majority of production for the fresh market is located around major

population areas. The greatest concentration of hothouse tomato production

occurs in the area surrounding the Auckland metropolitan district.

It is claimed by the New Zealand hothouse tomato industry that the profitability of this form of production is dependent upon the achievement of reasonably high prices during the winter period. This achievement, it is suggested,

enables growers to produce tomatoes during the summer period in competition

with the outdoor grown tomatoes and enables the acceptance of a lower price

during that period as the majority of their costs have been covered during the

winter production season. There is therefore a considerable degree of crosssubsidisation between the winter season, which is exclusively supplied by

the hothouse industry, and hothouse production in the summer, when outdoor

grown tomatoes are also available.

3.2

Production Costs

The

Growers'

cropping

November

Protected Crops Profile Committee of the Vegetable and Produce

3

Federation has undertaken a survey of the Auckland region protected

industry for the 1981-82 season. This research was reported in

1982 (Protected Crops Profile Committee, 1982).

The report established that approximately 78.5 per cent of the total

value of output of the protected crop industry in this area was from sales

of tomatoes which amounted to approximately $13m for the 1981-82 season.

Other crops of importance were carnations at 10.8 per cent of the total

revenue, cucumbers at 5.4 per cent and grapes at 2. I per cent. The total

protected area allocated to tomatoes was approximately 607,000 square metres

with 386 growers reporting that they were involved in tomato production.

Approximately 90 per cent of growers had

3,000 square metres with 79 per cent being on

metres. Approximately 60 per cent of growers

properties for less than 10 years with nearly

properties for more than IS years.

protected areas of less than

areas of less than 2,000 square

had been occupying their present

31 per cent being on their

The major sales outlet used by protected crop growers was the central

market (or auction system) with 83.6 per cent of the value of produce passing

through that outlet.

The number of persons employed on an equivalent full-time permanent

basis was established at approximately 860 in the Auckland area. When

casual labour is included in this calculation, the total employment on an

equivalent full-time basis was determined'at approximately 1,200 persons.

3

Crops growing under environmental protection (mainly glasshouses).

13.

The information presented in Table 5 provides a summary of the financial

data reported in the Protected Crops Profile Committee Report, 1982

TABLE 5

Auckland Region Production Parameters 1981/82

Average

for Region

Number of Properties

469

Average Production:

kg/m2

17.20

7 kg cartons/m2

2.5

Average Price:

$ / carton (7 kg)

I 1.44

J. 63

$/kg

Average Income:

29.00

$/m2

Average Costs:

Production Costs $/m2

Overhead Costs $/m2

I 1.17

Total $/m2

19.88

$/carton (7 kg)

8.71

7.95

Average Net Profit:

$/m2

9.18

$/carton (7 kg)

3.67

Source:

Protected Crops Profile Committee Report (1982), "A

Profile of the Auckland Region's Protected Cropping

Industry 1981-82 Season", New Zealand Vegetable and

Produce Growers' Federation.

These data indicate that the overall average cost of production for a

7 kg carton of tomatoes for the 1981-82 season was $7.95 ($1. 14/kg). The

data also indicate that this cost was associated with a net profit of $3.67

per carton ($0.52/kg) and an average price of $11.44 per carton ($1.63/kg).

An important element of the financial profile which has not been reported

is the degree of variability over the year in the volumes of product marketed

per month and the prices received for that product. As there is a marked

seasonal variation in price and quantity marketed, the impact of any variation

in the monthly supply on the grower returns will be considerable. Any analysis

that does not take these factors into account can therefore only be indicative.

14.

3.3

Product Supply and Market Prices

A breakdown of a grower's sales and returns during 1982 is given in

Table 6 (N.Z. Commercial Grower, 1983). This analysis indicates a consistently

high price between the end of August and the middle of November when sendings

to the particular auction were low. However, this information can only also

be considered as an indication of the likely return given that there will

be considerable variations in price according to the quality of the product

sold and the general distribution of product supply to the market.

The Department of Statistics has provided a monthly analysis of average

prices for tomatoes sold at auction for 1980, 1981 and 1982. This information

is presented in Table 5. Figure 2 illustrates the seasonal nature of tomato

prices.

The following auction companies were contacted and asked to provide

information on tomato revenue and quantities sold on a monthly basis for

1981 and 1982: Produce Markets Ltd, Turners & Growers Ltd (Auckland),

Radley & Co. Ltd, Turners and Growers (Wellington) Ltd, MacFarlane and

Growers Ltd and Market Gardeners Ltd. The informativn requested has, however,

not been provided.

IS.

TABLE 6

Tomato SupplZ and Price at Auction 1982

(Single Grower Records)

Week

Starting

June

July

August

September

October

Quantity

(cartons)

Source:

a

a

Average Price

($/kg)

21

5

10.08

1.44

28

45

16.29

2.33

5

136

10.28

1.47

12

81

10.32

1.47

19

80

12.43

1. 78

26

114

11.86

1. 69

2

110

9.83

1.40

9

156

9.60

1. 37

16

136

13.71

1. 96

23

142

13.93

1. 99

30

121

22.60

3.23

6

77

23.62

3.37

13

66

17.45

2.49

20

53

17.69

2.53

27

55

16.70

2.39

4

67

16.17

2.31

11

43

22.51

3.22

18

36

29.89

4.27

25

35

23.44

3.35

56

19.14

2.73

8

71

19.31

2.76

15

82

6.62

0.95

22

/17

6.80

0.97

29

97

6.17

0.88

6

84

8.65

1. 24

13

94

7.70

I. 10

20

52

4.54

0.65

27

10

4.80

0.69

November

December

Average Price

($/7 kg carton)

"How Imports Could Put Growers out of Business", N.Z. Commercial

Grower, Vol. 38, No. I, January/February 1983; N.Z. Vegetable

and Produce Growers' Federation Inc.

The average price per 7 kg carton for the June to December period

was $13.24 ($1.89/kg) for the 2221 cartons sold.

FIGURE 2

4 ..

Average Monthly New Zealand Tomato Prices

,.

1980

---0

1981

)Co- - - - - t (

1982

)4

0- -

3

$/kg

2

~

/J\

/~~~--~ \

\

~

/

\

/

r

/'

//

I

/

I

"'~-~:.

-d

-.j/

I' .....\

-0- - -

o Jan.

Feb.

Mar.

Apr.

May

June

Months

July

Aug.

Sept.

Oct.

Nov.

Dec.

.......

SECTION 4

THE POSSIBLE AUSTRALIAN SUPPLY IMPACT

The level of Queensland tomato production and the growth of production

that has occurred indicate that there is a considerable potential for Queensland

tomato growers to supply tomatoes to the New Zealand market. Such supply

would be economic when the price on the New Zealand market exceeded $NZI7.00

per 10 kg carton ($1.70/kg). (This is equivalent to $11.90 per 7 kg carton.)

This conclusion is based upon the likelihood that supplies of Queensland

tomatoes would be airfreighted to New Zealand rather than consigned by sea.

This assumption is likely to be valid as the time delay in transporting

tomatoes by ship would be considerable and would tend to have a very significant

effect upon the shelf life of the product once it arrived and was sold in

New Zealand. It should be n.oted that further developments in controlled

atmosphere transport systems would tend to make shipment of tomatoes by

sea a more attractive proposition.

From the information provided in Table 7 it can be observed that the

export of tomatoes from Australia to New Zealand could be attractive from

June until November. This is the period when the average New Zealand price

exceeded $1.70/kg in 1982. Under the most pessimistic assumptions, it

could be suggested that the average price for tomatoes would be reduced

to a maximum of $1.70/kg over the period when Australian imports were occurring. This would reduce the annual simple average price from $2.08/kg (from

Table 7) to $1.46/kg. This is a reduction of $0.62/kg or a fall in the

average price of 30 per cent. Such a fall in prices would result in increased

demand for tomatoes. It is assumed that the increased demand would be met

by imports from Australia. From the average prices given in Table 5, a

fall of 30 per cent from the average of $1.63/kg is equivalent to $0.49/kg.

Average production per square metre is given as 17.20 kg. A price reduction

of $0.49/kg would ,therefore be equivalent to $8.43/m 2 . Such a decline would

reduce the average net profit from $9. 181m 2 to $0.75/m2. This would be likely

to result in a decrease in the New Zealand supply of tomatoes. Australian

tomato supplies would then be required to offset the reduced New Zealand

tomato supply as well as meet the additional demand resulting from the decreased

price. Such a situation would require substantial tomato supplies from

Australia.

The situation as described should be regarded as an extreme scenario.

The aspects of Australian supply volume and quality differences must be

considered.

The level of access for Australian tomatoes is given in Table I. The

access level can be converted into equivalent tomato quantities using the

assumed import price. These quantities are given in Table 8 where the

January 1983 price has been given as $1.70/kg and inflated at 10 per cent

per year.

From the analysis given in Table 8, it can be observed that annual

Australian tomato supplies can only be between approximately 100 and 177

tonnes up to June 1988. This is equivalent to between 0.38 per cent and

0.68 per cent of total annual average freshmarket production (for 1975-1981)

and 0.57 per cent to 1.01 per cent of average hothouse production (from

Table 4). This level of Australian supply is not likely to have any significant impact on the total New Zealand tomato market. If the total additional

supply were to be directed to anyone market over a short time period, some

19.

20.

TABLE 8

Access for Australian Tomatoes - Quantity

(Assuming a 1983 eIF price of $1.70/kg and a 10% inflation rate)

kg

January 1983 to 30 June 1983

44, 118

July 1983 to 30 June 1984

101,471

July 1984 to 30 June 1985

J 16,692

July 1985 to 30 June 1986

134, 195

July 1986 to 30 June 1987

154,325

July 1987 to 30 June 1988

177 ,473

impact could be expected, especially where product is sold through an auction

system. However, this is more a result of the marketing system used and

the consequent over-reaction of the price to changes in supply. Where growers

establish firm supply arrangements with specific buyers, the price impact of

the Australian supplies is likely to be very small.

It should be noted that the average annual variation in New Zealand

hothouse tomato supply for 1975-1981 was 2532 tonnes. This variation is

14-25 times the allowed access for Australian tomatoes through to 1988.

The effect of local hothouse supply variations could therefore be expected

to be much greater than that likely to occur as a result of imports from

Australia.

It is, however, probable that where imports are concentrated in any

one area (city) the price impact could be substantial over a short period.

However, it would not be in the interests of Queensland exporters to drive

prices down for the small volume of product they are able to send to New

Zealand. Therefore, it is more likely that product releases on the New

Zealand market would be under some commercial control. The longer shelf

life of Floradade tomatoes would contribute to a controlled release onto

the New Zealand market.

Quality differences between Australian and New Zealand tomatoes must

also be considered. A likely situation is the replacement of poor quality

New Zealand tomatoes with the supply from Australia at the lower price ranges

while the price for top quality tomatoes continues to be high.

This scenario

is based upon the observation of the quality of Australian field crop Floradade

tomatoes. The type of tomato is significantly different to that produced

in New Zealand. The taste characteristics, the shape and the skin texture

differ from that presently accepted by the New Zealand market. It is generally

agreed that the Queensland product is of an inferior quality to the product

presently available in New Zealand and that the Queensland tomato type usually

competes because of its high yields, low per unit production costs and long

shelf life. As the Queensland product would still be at a comparatively high

price (i.e. versus the prices achieved during the summer period in New Zealand)

the product may not be as acceptable to consumers as the traditional New

Zealand tomato type. This would mean that the Queensland product would move

into

lower quality areas of the market and would therefore tend to replace

21.

part of the poorer quality production of the New Zealand varieties at a lower

price. This may encourage an increase in consumption at the lower price end

of the market which may tend to absorb the limited supply of Queensland tomatoes

that would be possible under the CER arrangements. The impact on the price

achieved for higher quality glasshouse produced tomatoes in New Zealand may

be small. Where New Zealand growers are able to establish a satisfactory

marketing arrangement that ensures the price for higher quality product is

reflected in the returns that they receive, their ability to compete with

supplies from Australia would be enhanced. This may require movement away

from the traditional auction system of tomato selling to, perhaps, a co-operative

approach to price negotiation between groups of producers and individual buying

enterprises.

It is considered that the most likely result of access for Australian

tomatoes to the New Zealand market would be some further economic pressure on

growers who are at present operating on a marginal basis and the encouragement

of increased efficiency amongst the remaining growers of high quality product.

The price required by Australian growers will ensure that supply will only be

viable for six months of the year. Also, the present access arrangements only

allow for very small quantities to be imported and the price-effect of these

imports is likely to be small. Over the longer-term, when access levels are

likely to increase substantially, more pressure on the New Zealand hothouse

tomato sector is probable. Increased competitive pressure from Australia

is likely to result in some reduction in New Zealand hothouse tomato production.

The time span over which this will occur is relatively long, however, and

alternative uses for the resources employed in the sector, are likely to be

available. In any case, the capital resources involved in hothouse tomato

production should have been written-off prior to the competitor pressure

becoming substantial. Where the quality aspects of New Zealand hothouse

tomatoes are effectively emphasised, the premiums available are likely to

be adequate to ensure that a continuing supply is required, at a lower level

than at present.

Reduced production of New Zealand hothouse tomatoes is likely to result

in reduced summer supply from this source as well as in winter. Any price

increases in the summer would however, result in increased outdoor tomato

production and any price changes are therefore likely to be small. Overall,

the annual average price of tomatoes in New Zealand is likely to be lower,

with a higher level of consumption, reduced hothouse supplies, increased

outdoor production, and increased Australian supplies.

REFERENCES

Anon. (1981); The Who, What and Why of Fruit Distributors Limited.

Fruit Distributors Ltd, Wellington.

Anon. (1982); A Profile of the Auckland Region's Protected Cropping

Industry 1981/82 Season. Protected Crops Profile Committee, Vegetable

and Produce Growers' Federation Inc., Wellington.

Anon. (1983); Australia New Zealand Closer Economic Relationship.

Agreement. Government Printer, Wellington.

Trade

Anon. (1983); How Imports Could Put Growers out of Business; N.Z. Commercial

Grower, Vol. 38 No. I; N.Z. Vegetable and Produce Growers' Federation Inc.,

Wellington.

Anon. (1983); New Zealand Horticulture Statistics, 1983; Statistics Section,

Economics Division, Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, Wellington.

Muldoon, R.D. (1982);

Press Statement, 4 June 1982.

Sing, W.C. (1981); Costs and Returns - Tomatoes - Bowen; Farm Note; AGDEX

262/821, No. F 100/Jul 81; ISSN 0155-3054, Queensland Department of

Primary Industries.

Wickstead, L.T. (1982); Costs and Returns - Ground Crop and Trellis Grown

Tomatoes - Buudaberg District; Farm Note; AGDEX 262/821, No. FI/Jan B2;

ISSN 0155-3054, Queensland Department of Primary Industries.

Wilson, R. (ed.) (19B3); Prices and Market Throughput on the Brisbane Wholesale

Market, Rocklea. Marketing Services Branch, Queensland Department of

Primary Industries, Brisbane.

23.

APPENDIX

Tomato Production Costs - Queensland

I.

Bowen Region

(Source: Farm Note: AGDEX 262/821 No. FIOO/Jul 81)

(Assumed yield 15 000 kg per hectare)

(Costs as at July 1981)

Preharvest costs:

$A/ha

Land preparation

Planting

Fertiliser

Crop Protection

Irrigation

$A/IO kg Carton

56

308

180

714

55

Total

$A 1,313

$AO.87

Harvesting and Freight Costs:

Picking and packing

Freight

I. 72

0.80

Total

$A2.52

Selling Costs:

Commission, levy, sales promotion

- 12.33% of gross income

Handling costs - $AO.02/carton

$AO.74

0.02

$AO.76

Variable Costs Summary:

Preharvest Costs

Harvesting and Freight Costs

Selling Costs

$AO.87

2.52

0.76

Total Variable Costs

$A4.15

In order to convert the cost from a July 1981 level to a January 1983

estimate, the Queensland Department of Primary Industries recommended the

use of a 10 per cent annual rate of increase, viz.

July 1981

July 1982 (+10%)

January 1983 (+5%)

$A4.15

4.57

4.80

25.

26.

2.

Bundaberg Region

(Source: Farm Note: AGDEX 262/821, No. Fl/Jan 82)

(Assumed Yield 75,000 kg per hectare)

(Costs as at January 1982)

Preharvest Costs:

Land preparation

Planting

Fertiliser

Crop Protection

Irrigation

Total

$A/ha

$A/ !okg Carton

234

1630

938

2702

1650

$A7154

$AO.95

Harvesting and Freight Costs:

Picking and packing

Freight

$AI.83

0.90

$A2.73

Selling Costs:

Commission, levy, sales promotion (12.33% of

gross income)

Handling costs

$AO.76

0.02

$AOo78

Variable Costs Summary:

Preharvest Costs

Harvesting and Freight Costs

Selling Costs

$AO.95

2.73

0.78

Total Variable Costs

$A4 .46

In order to convert the cost from a January 1982 level to a January 1983

estimate, the Queensland Department of Primary Industries recommended the use

of a 10 per cent annual rate of increase, viz.

January 1982

$A4.46

January 1983 (+10%)

4.91

27.

3.

Coastal South-East Queensland

(Source: K. Bengston, Farmer, pers. comm.

Department of Primary Industries)

(Assumed yield 30,000 kg per hectare)

(Costs as at January 1983)

Confirmed by Queensland

$A/ha

Preharvest Costs

4500

$A/lOkg Carton

I. 50

Harvesting and Freight Costs:

Picking and Packing

Freight

$AI.80

0.70

$A2.50

Selling Costs:

Commission, Levy, Sales Promotion (12.33% of

gross income)

Handling Costs

$AO.84

0.02

$AO.86

Variable Costs Summary:

Preharvest Costs

Harvesting and Freight Costs

Selling Costs

$AI.50

2.50

0.86

Total Variable Costs

$A4.86

RECENT PUBLICATIONS

RESEARCH

105.

135.

REPolrr's

Potatoes: A Comu7rJi?f Suroiyof Chri§!tburchand Auckld'rdHoUJe-

SJ.irt;eyoj i-lfew Zealand Farmer Infeiztioizfand Opinions, J!I!Y~

Sepie'nber, ]979,J:G. Pryde, 1980, .

.

107. A Survey oj Pestnmd Pestidde. [}sefl1 Canterb£!yyandSouihia;·u/.

JD~ M11mford, 198(L.

.

.'.

..

.

.•.....

108. '. Aj,Ecoiujmic Sm7!eyo/iVdvZea14nd. Toliin Milk PYfJditcers, i97g:

79, RG. MQffit(1930..

'..

. ....

109. Chango', ill UmiedKz;"1gdim llfleai Deindnd,RL ShePi?ard;.

106.

1980~

.

i983.

1980.

'.

.'

. . . . . . ..... .' ..... .

.AnATlalysis ojAlternaJive WbeatPricing Schemes; M.M. Rich;

LJ Foulds, 1980'.

.'

...... ..•....... .•........

M.M. H.ith,-1980,

Multiplie,'s fro", Reg/oQal.Non~Sttrvey.lnP!it-O!itpritTI1.bir:sfor

New' Zeid:in.l.~ L.J·:I:"Iu:1?bard \Xl:..lL~~ Bro::vn... 19~.r:;

118 Smve-j of the H eafth of NeY.} Zealand F arJlle;s.' Ot:tober~ NovemiJ.er

1980) ].G. Pryq.e 1981.

..

119 I-fari"ia.i!ture il2 Aktiroa County,

RIo. Shepparii..., 19EP~

An Economic Survey 0/ NewZeaiand Totv1! Milk ProdlJcers,1.979-'-

117

EconomiCkelationship; witbin ihejapaniseFeehmdLivestoci.·.

Sector, M. Kagatsume, AC Zwart, f983.

.

.

49:

The Cost oj Overseas Shippi,1g: Who

DISCUSSION PAPERS

·50

. 55.

J.

56.

7

SO, i1~G. Ivfoffit~:!<~9En.

121. . Ail :E.cO)-;o)'lJ,ic S;.j'lVej! of ]Ve-di 'Ze!1~aT1d hV7hetitgrozi!e;?". ·.Ef1tiirPr~~~

./i;u:fy5iJ~_ Si1,,·ziey]vo. 5 1980-81>7 R. D~ L011gh, P.]: ¥cCartin,

MJvL }lic"i-"i] 1981.

.

.

i23.

'57.

18.

. 59.

.

.

.

S.hcpparci, 1.982.

l'l5e f\Jr:;UJ .Z~e{xi'j?!r!1Jvheat (flit/Flo1-1,? IrJdustry.- .iviarket ~tr!.t~~.~~ it"nd"

Policy Xmp!it:.:Jt:!o.'1J, B·.l,~·. Bo:rYell~ A.. C~ Zwart; 1?l8l. . : ..

125.

Tbe ECOYfl'JITJics of Soil', COiJ-fervai'ion OJ::d· Wat~r ..IIlQn.'!c;6r!ent

J?olicii.·J in t~e .Otago ijigb·CotJ7i.t'i'Y~ G~T.·Harri~,.?~~~._: .'. "

126.

St!J"vry of Flew Zealand F~'mi.?7 J;-ztmtirJIIS a.1d OpiJit'ons,Se"pttfrnberNovembei, 1981, ].G. Pryde, 1';}82.

. ' ..... ~

The New ZealdndPostordDves/oc.k Sector: Ail E!:{;'li8mdtii/M'-ode!"

(i/emo71 TtvoI M.T.Laing, 1982.

. ',«

128. A Farm-love/.Madetto E';tiluate the .impactsof c:!t"rr~llt Energy

Policy OptiO>7J, A.M.IvL rhompspIl, 1982.

..

.....

Ail Economic Stlri1ey ojNezu. Zedland Town .Milkl'rodij;~rJ 1913.r)~

81,

130.

131.

132.

RG.

Moffitt, 1982

'[be New ZeaijiidPofatoMarketing Systffllj

1982.

.

.'.

.....

'ItLSheppai-d/

.... .•....

An Ecollllmic Survey oflVew Zealand Wbeat-growe7Tf.~t~jJrisi

lJlllilysL~ S!!rrfey /:[0.

19fJ1-82,ICD.Lough, P,J;l\1cCairlii/

lVLM. Rich, 19SL

..

... .

An EWl/{mic Survey of New Zedarld WbeatgrolVers:Fi11,1Flcial

,Ailf]~VJtJ~. 19BO-8J._ ~D.· L<;i:ugh, P-J. lv1-cCartiI), 198~:· .

.

Tbe BE C Sheepmeat Regime:' Arrangements'ttnd ImpliclJtions,

N. Blyth,. 1980.

....

Proceerlings ;/a Seriiindi- OJ1 FittttreDirect!o;sforNewZealand

La172bJllIarketing. edited byRL Sheppaid;Rj:'1:3rqdie~19S0,

.The Evaldation of Job Creati071ProRrarr:~elwitb.Partr~ltIar

Rejefe11£';' trj the Farm Emj>ioyment Pmi!.rtimmr:, G. T. HartiS>

1981.'

.

.'.

..

.

nf New Zealand Pew'oral Livt/Jt~dc Sector-: a jJte!imzl{ary

.ewfmmeiric model. M. T. Laing, A.C'Zwart, ~98L .

.

TheSchedll/f?f'rii"e System and theiVewZea!onJpmoProdlJcer;

N.M; Shidboit, 198.1.

.

The ,FJIY"/her Prot(,5.ring fJf Mt'a!, K. M. Silcod:, RL Sheppard,

198L

. Japanese .-1,~riclI/tll?"a! Polity Developme."1!: Imp/ieattonI/or NeuI·

Zealand. A: C Zwart, ] 981.

. '

!l;teresl RqtcJ:

Fact's

and Fallacies, leE. Woodford. 1981,

The EEC Sbeepmeat Regi-me: One Year On, N. Blyth; 198L

62.

The New Zealand Meat Trade in ,be ':980',-: a proposalfor change;

B-J-Ross,R.L Sheppard, A.C. Zwart, 1982. '.

SU?p!eia¢?!tary lVft!Ji~!Jm Prices: a production .t:~c¢7Ztlp¢? R.f.~

Sh.eppatd;J.M. Biggs, 1982.

Pfoceedingsoja Seminar on Road 'Transparlin RuralAYeas, ~dited ...

by P~D.Chudleigh, AJ. Nichoison, 1982; .

. .

.

J\L Blyth; 1981.

.·63.

Evaluolion of FB'i7lJ

K.B. Woodford, 1981.

{)WT.?TS£lip

Sayings

Accoz!Jitj~

QiJality int~e New Zealand Wbeat and FloUI'Marhets,M.M.

Rkh,1982.

'.

.....

.'

66;

DeSign . CO~Si(le-lations jor Computer Bas~a..Miltket~·ngand

Irzjo-/mation Systi:1ns, .P.L Nuthal!, 1982:"

..'

67.

ReagaJ']of72its'dtid fhi New Zealand

I3ohaJl; 1983.

Agricplf!lral$.e~(Ofii;w:

.

.'

68 . '. '.' Energy. We in N~w Zealand Agrii:Jif::m:!fprodllct!o~,'iDi" .

69

¢hudleigh,Glen'breer,1983.

.c·

Ft,rm j:ina~r:eDatti.: Avazlability alid Reil"/re1l1e';ts>Gl~n G~eer,

.1983

. ..... .... '.' . '

'.

6,

Th;

.

P~storaiiivesto!:k

.

-

-

Sector and tbe SitppleJJzentJ&:Mt17t1l1um

Price Poiicy,M;T. Laing,

A.c. Zwart, 1983;

.

.

.

71.

.Marketing Im'titlltiOf/S for Neif.l Zealand Sbeepmetits,ACZ.wart,

·fo~~

72.

S!lpporting fbe Agriculturtil Sel:tor:' RatiOllale and PoliGy, P.D.

ECOlJOrfh!:,r

,?/ !-'he Sbe.ep B'Tee~/iilg Operation; of the DepoT/ment 0/

73.

!jJZlq

La.m{r

SJ';"OJc,)"

133. /1lt :;']';It.n'iu.t.-,

JH(/7J£lge!l?t'?I~<. ~;r~'~Jgi~J

Jrr"·~~'(l(.,!c! r:al'licrbftrjl

134.

. .

.

.

Lin

127.

129.

Green

Spiqu!iiig Broi:colJ; R.L Sheppafd.1980:

61.

. ,

124.

Chudleigh,

A Review. oj {,be World S}Jer:jJn,eat Market: Va!. j ~ .Overvie-.u of

In/ematfono! Trade, .vol. 2 - .t1lhTTalia; New Zealond&A,-gjlfJ1tint:f,

Vol. 3 - 1;~eEEC (10), VotA - North America, Japal1& The

il'liddle Etm~ Vol. 5 - Et25te?1J Bloc, U.S.S.K &. l'llongolia,

.

S,?t!j"orJal;~)! it.! tbe l\f..~;; .Ze?iland Afeut Py'ocessing I~d~itry~. ·Itt.

Pays? Pop,

1980..

Market EViJlu(liio~: a Sysle7llaticAppro(2ch~Fmzeiz,

60.

~~a~~f;;[:;~9~;;~_K ir~:~~?~~f f:!~ft:,e:~.::n::~:

1.931.

.

14°·

11.3. An Econorlt.1c Suweyoj New Zealand Wheatgrower"s;:E11terjJrisi< 51.

An:lysij, Slimey tva 4 ~~7?-80, RD. Lough,RlvL MacLean,"

P.J. McCawn, M.M. .Kich~ 1980.

.

.....••....

114. A Review oj tb.e Rural eredi".! System in ReI{! ZedliJiid,1964

1979; J.G. Pryde;S.K~ Ma~tin, 1980.

.

.' .

115. ·A Socio- Ecorw)YzicStudy of Far??! Workers afJd Farm' Md1iagt;r5,:'

G.T.Harris; 1 9 8 0 . .

..

116. An EC07iOl7lic Suroey·of.New·Zcaland Wheatgrowd;j;F(m:J"l1dal

, 54.

Analysis, 1978-79,RD. Lough, Rll.1.: MacLean, PJ. Mceartin;

122.

...'. .

139: AT/Economic Sljrveyojliew Zeti~nd T{}w~Milk PrOducers, .198182, RG. Moffitt, 1983;

..

....

. .

jjrureflosis Eradication: a descrtption oj a planning irlOdel,.kC.

Beck, 198.0.

.

,.. .

111.. F/sh: A ConSlJm~rSMroey ofChristchurch Hotisel;oldS;~J- Btbdi(:l,

112.

Survey of New Zealand Fanner IntentionJandOpinions, OctoberDecember! 1982,J.G. Pryde. P.J.McGirtin,1983:

137. IJi.ves/ment and Supply Response in the N.di'ZctlitmdPastrJra!

Sec/or: AT/ EcojlOinetr/cMIJ/{el. M.t~Liing;A.C.fv,>'art, 1983

TiJe .World Sheepmeai Mill-kef; aiJ ew~omejric model; N. Blyth,

136.

. holdj, M.M. Rich, }iLJ. Melior>.; 1980.

110.

Water and Choice i11 Canterbury. K.L Leathers, B.M.H. Sharp,

W.A.N.Brown,1983 .

'..

dYf.J

Sbee.b F!.!rmJ.

Ci!7ti

l\I_~\tL

DrrlJftiilg

Policie"j

Shadbolt. 1982:

A. T~G. J1.AcJ\.rthur, 1983.

i9B3.

.

Chudleigh, Glen Greer, RL. Sheppard. 1983.

Re!atillg to the Funding of PrimaryProtessillgReJearcb

Throllgh R eJearch Associa/lollI, N. Blyth, lLC. Beck, 1983.

!~,_ddit.i.:::nd '.:-opies ofResea.rch R.eport3, ;.;lpart from complimentary copies? are available at :~6.00 each. Discussion

a~e usu~.lly $4.00 bu't COpi.ES GfConference Proceedings (which are usually published as Discussion Papers) are

o;,~~. :C;iS':'ES5~OD Paper I'fo.

is available ;l1:.~4.00 per. volurne(S20 for the set). Remit,(2..I!ce shou!d accornpany orders

~" ..;.... l;"~:~:,·::d (;): J3ookshop, LiIlc01.n Co(L:ge, C3.l.:l:erbury, l\J(~w Zea.!.?nc. Please add ~)O.90 pe:.: Co:)?}," to cover postage_

on