Mining For Psycho-Social Dimensions through Socio-Linguistics

advertisement

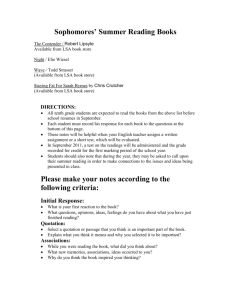

Sociotechnical Behavior Mining: From Data to Decisions? Papers from the 2015 AAAI Spring Symposium Mining For Psycho-Social Dimensions through Socio-Linguistics Peggy Wu, Christopher Miller, Tammy Ott, Sonja Schmer-Galunder, Jeff Rye Smart Information Flow Technologies PWu@sift.info; CMiller@sift.info; TOtt@sift.info; SGalunder@sift.info; JRye@sift.info can cause survey fatigue among participants. During debriefs, some of our study subjects questioned the validity of the answers they provided, despite their best intentions and efforts to provide accurate data. A data collection tool and validated analysis methods that utilize naturally occurring behaviors will alleviate survey and reporting burden. Such a tool would not only be useful in research, but we believe that it could be used to facilitate the selfmonitoring of psychosocial dimensions through automated analysis of communications or narrative self-reports such as journals. Abstract Communication is social by nature, and reveals psychosocial dimensions about an actor’s perceptions of themself and others. While grammar and spell-check can help polish the presentation of communication, it does not reflect the way that a message will be received in a particular social space. A means to analyze the communication for actor beliefs can help the author and others understand the underlying social climate and message that is being transmitted. NASA has identified the need to monitor individual behavioral health and team dynamics as crucial to ensuring high performance and mission success. We describe an application that integrates theories from sociolinguistics with natural language processing techniques to successfully detect individual moods, attitudes, and team dynamics relevant to long duration exploration class missions. The methods were used to analyze data gathered from human subject experiments at three diverse analog studies, with results showing high correlation with subject self-reports and third party observations. We discuss preliminary results and implications for the tool’s potential wide-spread use. Virtually all team performance and psychosocial problems manifest themselves in “transactions”—interaction and communications between team members. (Salas et al. 2007, p. 189) define a team as “two or more individuals who interact socially and adaptively, have shared or common goals, and hold meaningful task interdependences.” Communication behaviors can be a rich data source for identifying and evaluating team health indicators. Communication, with all its nuances, may be even more important for long duration space flights (Stuster 2010) especially under the circumstances of social monotony, possible discrepancies in cultural assumptions, and delayed communications with ground crews. Therefore, our approach examines observable communication behavior to detect and assess factors affecting team dynamics and individual emotions. Introduction and Motivation Future astronauts will work in a unique environment in which they are placed in multicultural teams and are socially isolated and confined to a small environment for an extended period of time, all while subject to constant monitoring and scrutiny. To evaluate relevant psychosocial states at both the individual and team levels, an accurate, objective, repeatable, efficient, accepted and minimallyintrusive means of data collection and assessment is needed. In this domain and others for behavioral health, researchers heavily depend on the use of surveys. This reliance on introspection and surveys has many pitfalls for both participant compliance and accuracy, especially in the context of long duration missions. Survey data are subject to a participant’s memory, biases, vigilance, personality (e.g. some participants are simply not very reflective), and Communication behavior observations are inherently nonintrusive, represent a large portion of a person’s social and work relationships, and can be correlated with data from other measures (e.g. circadian desynchronization, extended wakefulness, work overload, task performance) to arrive at a holistic picture of serious performance threats and situational contexts where they occur. We developed such a tool under the NASA funded project called ADASTRA— Automated Detection of Attitudes and States through Transaction Recordings Analysis. The goal of ADASTRA Copyright © 2015, Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (www.aaai.org). All rights reserved. 33 sition of an act might start off as nominal, but we draw inferences from the transaction itself. When imbalance is perceived in an interaction, we try to explain it by adjusting our assumptions about the relationship or imposition— or the character and knowledge of the participants. is to create minimally intrusive, valid and efficient assessment methods to identify and track key individual and team psychosocial states using communications data streams and written introspection by leveraging analytic methods based in socio-linguistics and sociology theory. ADASTRA extracts individual and team psychological dimensions using spoken and written behaviors rather than surveys. The advantages of this method are twofold: firstly it allows unobtrusive detection to reduce subject survey burden and secondly, it enables in-depth data-mining to identify factors not identified a priori in surveys. ADASTRA techniques have been performed on data collected from multiple missions in three analog space exploration environments, as well as with historical spaceflight data. Our results provide empirical evidence of some hypothesized key threats and indicators for team and individual psychological health; they also uncover correlations that were not previously studied or anticipated. Below, we describe the ADASTRA system, the analog environments in which data was collected, and some of the results that support the validity of this analysis method. Brown and Levinson’s politeness model is a subjective framework that inspired our algorithms for detecting the difference between expected and exhibited redress behaviors. This differential can then be used to infer power difference and social distance between interlocutors. When combined with other measures such as attitudes and affect, we begin to arrive at a computationally tractable description of the complex landscape of social relationships and their changes over time. Related Work Over the past decade and a half, there has been a veritable explosion in social science research that capitalizes on the fact that more and more of our lives and activities are either conducted online or recorded via audio, visual and/or textual means. While many techniques exist to derive emotion from audio (e.g. voice prosody) and video (e.g. facial expression recognition), we believe a strictly semantic approach is needed for those data sources that contain only text (e.g. written journals, blogs, emails, instant messaging, and other text correspondence). ADASTRA focuses on three primary techniques to derive insight from text: • LIWC—Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (Tausczik and Pennebaker 2010) is perhaps the best known of a family of software approaches that simply count the frequency (and sometimes the position) of words that a researcher targets. There are a variety of emerging empirical and theoretical approaches linking specific words and word classes to psychological, behavioral, and biological phenomena. • LSA—Latent Semantic Analysis (Landauer et al 1998) goes beyond LIWC by examining not just the occurrence of specific words, but the occurrence and relative position of words and their semantic equivalents. Records can then be characterized in terms of the concepts they contain and the proximity of those concepts—for example, the frequency of “jihad” and similar/related terms to positive emotional terms might serve to characterize the news articles in a nation’s press. • Etiquette EngineTM—Our own work (e.g., (Miller et al 2010a; 2010b)focused specifically on the appropriate use of politeness terms (broadly defined) as a measure for interpersonal relationships. We have explored the use of variants of both LSA and LIWC, but have been guided in their use by the role that politeness plays in managing and signaling relationships as expressed in the Brown and Levinson theory. This has the unique strength of guiding cross- Theoretical Background Much of our work has centered on a computational model of the role and interpretation of politeness in human interactions, based on the work of (Brown and Levinson 1987). Brown and Levinson proposed that the function of politeness is to redress the face threat inherent in social interaction. Goffman hypothesized that individuals are motivated by positive face (i.e. the desire to be seen as a valuable member of the group) or negative face (i.e. the desire to be autonomous) (Goffman 1967). In Brown and Levinson’s model, social interaction invariably threatens either or both of these aspects of face, and measures must be taken to maintain the social status quo. Brown and Levinson believe that politeness usage is one of these measures. The degree of face threat that needs to be addressed is a function of the power and social distance (roughly, familiarity) of the interlocutors, plus the degree of imposition of the interaction. We make use of polite “redressive strategies” to offset face threat. If less redressive value is used by the speaker than the listener deems necessary, the interaction will be perceived as rude; if more, then “overly polite”— but the value of both the threat and the redress is based on the perceptions of the individual, which are personally and culturally informed. This explains how the same utterance can be polite or rude depending on context—and how one individual can intend an act as nominal while another sees it as rude. A final aspect of the Brown and Levinson model important to our work is that politeness perception is a cognitive process. Our perceptions of social relationships and the impo- 34 cultural and cross-language interpretations of politeness usages, as we demonstrated for ISS crew in video records in (Rubino et al, 2010). Next, we describe how these techniques are used in the ADASTRA tool. The ADASTRA Toolset The goal of ADASTRA is to utilize naturally occurring textual data (e.g. journal entries, conversation transcripts, written communications) to derive individual and team psychological dimensions relevant to spaceflight. We believe that using observed behaviors as a data source can yield more insight, and perhaps more accurate insight, than self-reports and surveys. Figure 1 depicts the major components of the ADASTRA system. In addition to the textual discourse, we added components that analyze free text, such as journal/blog entries, using extensions of the LIWC and LSA techniques. We applied these methods to naturalistic data observed from spaceflight analog facilities. days and carry out science research tasks as well as spaceflight simulations. We collected journal and survey data, as well as transcribed speech and text chat from a total of 16 crew members. In summary, we collected a corpus of written and transcribed data from 45 subjects across three analogs. Next, we summarize our analytic methods for the different types of data collected from the analogs. We performed studies at three different ground-based facilities where various aspects of spaceflight were simulated. They include: Analysis Methods Bedrest—This facility’s primary focus is to study the effects of microgravity on human physiology. Participants undergo 14 days of intake protocols, and are then confined to bed rest for 70 days, followed by 14 days of recuperation and post-treatment protocols. They maintain a 6degree head down angle for all activities during the 70-day bed rest period. Participants are monitored by a human 24/7 to ensure compliance. We collected journal and sur- In our data exploration and through the process of adapting our methods to three different analogs, analog subjects, and data types, we expanded on known analysis and discovered previously unknown but significant analysis methods that address NASA’s concerns about team and individual psychological health. Below, we provide an overview of a subset of methods used. Power Difference Network—Based on the Etiquette Engine and Brown and Levinson’s theory, this algorithm uses conversational transcripts to produce a snapshot of the power hierarchy among actors, similar to an organizational chart. For validation, these results were compared with a crew’s organizational structure. Individual crew members were assigned the roles of commander, engineers, or mission specialists, with the commander as the leader of the group. Crew members also completed surveys regarding their perceived power difference throughout the mission. Salience and Trend—This is a collection of keyword category counts. Trending topic frequency over time can provide useful indicators of emergent topics such as the unfolding of specific events or concerns (e.g. the emergence of concerns over a leg injury in a subject). The method also serves as a preliminary step to assist in down-selecting valence and other specialized techniques described below. Figure 1 Basic Architecture of ADASTRA vey data from a total of 18 bedrest subjects. HI-SEAS—The Hawaii Space Exploration Analog is a long-duration Mars simulation located in the barren landscape of Mauna Loa, HI, at an elevation of approximately 8000ft. In each mission, six crew members are confined to the isolated habitat for four month. They perform science research projects inside the habitat and conduct two to three Extra Vehicular Activities (EVAs) in the form of geological surveys outdoors while donning prototype space suits. We collected journal and survey data as well as crew to mission support written communications from a total of 11 crew members. HERA—The Human Exploration Research Analog is a Mars mission simulation based in Houston at the Johnson Space Center. It contains three primary modules where four crew members per mission are confined for seven 35 or present-tense verbs respectively. This measure is useful as it may be combined with others, such as sentiment towards past, present or future, to arrive at a measure of happiness versus meaningfulness (Baumeister et al 2013). • A significant negative correlation between the use of terms about physical state (both our own defined category and words derived from Tausczik and Pennebaker’s work) and survey ratings of physical state (rs=-.273, p<.001). Thus, subject’s increase in their use of terms related to their physical state was generally indicative of their reporting feeling worse. We do not believe that one can generalize this finding to the interpretation that increased mentions of any topic is automatically correlated with negativity towards that topic. However, this finding is consistent with the psychological phenomenon that bad events tend to “stand out” over good ones (Baumeister et al 2001) explains that negative emotions and events ranging from bad social relationships to physical trauma have higher impact on individuals and necessitate more reflection and processing across a number of domains, possibly because one is motivated to avoid future negative events. Note that the data source used is a journal where subjects are explicitly asked to reflect on their day. Valence - closed vocabulary Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA)—This provides trends of general mood as well as topic-specific sentiment (e.g. attitude regarding habitat, food). Some topics, such as general emotion, are based on work by (Tausczik, and J. Pennebaker 2010) and (Pennebaker, 2011), while others are manually generated based on the language-use specific to the source data (e.g. names of places, people, technical their semantic distance to the affective norms of English words (ANEW 2014). These results were compared with the Positive Affect Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), as well as survey questions. Specialized LSA: past/present/future—This collects and analyzes a subject’s use of words associated with the past, present, and future to provide insight into an individual’s temporal focus. These results were correlated with survey questions that immediately followed journal writing. Specialized LSA: self vs. others—This presents a subject’s use of words associated with him/herself as opposed to others, which provides insight into an individual’s focus and introspection. These results were correlated with survey questions that immediately followed journal writing. Results While our approach is proving powerful at finding general trends across subjects, we believe that its greatest contribution comes from its ability to track and identify cognitive, attitudinal, and emotional trends within an individual over time or relative to others. The degree to which our analyses provide accurate data for individuals is difficult to validate statistically, but we present several interesting ways to gain individual insights into the emotions and attitudes of individual crew members that will aid in both individual and team psychological support. • First, there were marked individual differences in word count per entry and in emotional content and ratings. While it is statistically true to say that most subjects showed a slow downward trend in PANAS positivity scores and in use of positive emotional terms over time, this is not uniformly true. For example, one subject showed almost no variation in his PANAS scores. Two others showed much more dramatic declines, while yet another actually shows a probable rise in PANAS positivity scores and positive emotion term usage. As of the time of this writing, we are in the processing of collecting, transcribing, and formatting data for analysis. Below, we present results using a subset of bedrest journaling and survey data. In general, the data has supported the validation of our methods. Below, we discuss a select set of findings. • A significant positive correlation between the proportional use of negative emotional terms (Spearman’s Rho rs=.187, p<.001), anger terms (r s=.179, p<.001), and anxiety terms (r s=.160, p<.001) (as based on (Pennebaker 2011)) and PANAS negativity scores. This confirms that when subjects rate themselves as having more negative mood, their journal writing reflects this. • A significant negative correlation between our past/present survey question (indicating perceived past focus) and use of past verb forms (r s=.-.314, p<.001) and significant positive correlation between our survey question and use of present (rs=.169, p<.001) verb forms. This confirms that when subjects see themselves as more past- or present-focused, they use a higher proportion of past tense 36 References Salas E, Stagl KC, Burke CS, Goodwin G. 2007 Fostering team effectiveness in organizations: toward an integrative framework. Nebr. Symp. Motiv. Paper, 52:185–243. Stuster, J. 2010. Behavioral Issues Associated with LongDuration Space Expeditions: Review and Analysis of Astronaut Journals. Experiment 01-E104 (Journals): Final Report. Accessed Nov 2010, http://ston.jsc.nasa.gov/collections/TRS/_techrep/TM-2010216130.pdf Brown, P. & Levinson, S. 1987. Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage. Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, UK. Goffman, E. 1967. Interactional Ritual. Chicago: Aldine. Tausczik, Y. & Pennebaker, J. 2010. The Psychological Meaning of Words: LIWC and Computerized Text Analysis Methods. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, Vol. 29(1), 24-54. Landauer, T., Foltz, P. & Laham, D. 1998. Introduction to Latent Semantic Analysis. Discourse Processes 25, 259–284. Miller C., Ott T., Wu, P. and Vakili, V. 2010a. In Blanchard, E. and Dalhousie, D. (Eds.) Handbook of Research in Culturally Aware Information Technology: Perspectives and Models. IGI; Hershey, PA., pp. 387-411. Miller, C., Schmer-Galunder, S. & Rye, J. 2010b. Politeness in Social Networks: Using Verbal Behaviors to Assess SociallyAccorded Regard. In IEEE Second International Conference on Social Computing, Aug 20-22, Minneapolis, MN, pp. 540-545. David, E., Rubino, C., Keeton, K., Miller, C. and Patterson, H. 2010. An Examination of Cross-cultural Interactions aboard the International Space Station. NASA Technical Report prepared by WYLE Scientific, Sept. 24. J. Pennebaker. The Secret Life of Pronouns. Bloomsbury Press, NY, 2011. ANEW dictionary accessed Oct 2014: http://personal.stevens.edu/~rchen/readings/anew.pdf Baumeister, Roy F., Vohs, Kathleen D., Aaker, Jennifer L., and Garbinsky, Emily N. (2013). Some key differences between a happy life and a meaningful life. Journal of Positive Psychology DOI: 10.1080/17439760.2013.830764 Baumeister Roy F., Bratslavsky Ellen, Vohs Kathleen D., Finkenauer Catrin, 2001. Bad is Stronger Than Good. Review of General Psychology Vol 5. No. 4 323-370. Accessed Oct 2014: http://assets.csom.umn.edu/assets/71516.pdf Figure 2 A depiction of general positivity and negativity of journal entries for one individual using LSA analysis • LSA Valence analyses can be calculated for individual subjects over time and can be used to provide an indication of emotional state (as inferred from the journal entries). Figure 2 provides a daily computed valence score for a subject, along with two representative journal entries for high and low valence points. LSA sentiment analyses give us a finer-grained sense of what individual subjects are feeling good and bad about by comparing the overall valence scores for their entries to the topics that correlate with those scores. This analysis can be extended to be topic-specific so we can derive the LSA valance for food, exercise, habitat environment etc. over time. Conclusion and Discussion ADASTRA can act as a monitoring tool to “listen in” and alert when something has, or seemingly might, go awry. It can be highly customized to individuals and can provide an objective third person perspective for corroborating with other subjective opinions. Sudden and unanticipated shifts in power, social dynamics, and individual general emotions and sentiment can indicate potential problems while helping to identify positive events that are otherwise not obvious. A nonintrusive method of detecting them can help make the connections between precipitating events to changes in moods and attitudes. We believe that self-monitoring might be an ideal application for such a tool to help an individual increase selfawareness. It can also inform an author about how a message might be perceived by others before the message is sent. ADASTRA can enable the objective self-monitoring of psycho-social dimensions, physical wellbeing, and perceived workload, all of which in turn help individuals improve their own abilities to recognize reasons and catalysts for changes in individual moods and team climate. Acknowledgments The above work was sponsored in part by the U.S. Office of Naval Research under contract # N00014-09-C-0264 and NASA’s Human Research Program under contract #NNX12AB40G. We would like to thank our ONR program managers Dr. Martin Kruger and Ms. Maya Rubeiz for the opportunity to participate in the 2013 Empire Challenge military exercise at Ft. Huachuca, AZ. We would also like to thank our NASA sponsors Lauren Leveton, Laura Bollweg, Brandon Vessey, Holly Patterson, the BHP element, and the subjects and staff at the various space- 37 flight analog facilities for their oversight, direction, and support. 38