BEYOND HONG KONG: IS THE DOHA DEVELOPMENT ROUND DOOMED?

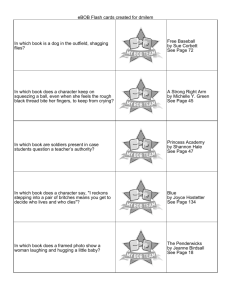

advertisement