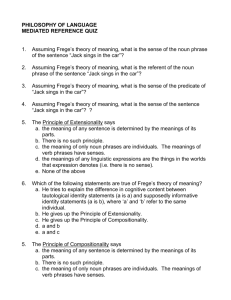

Did Frege Believe Frege’s Principle? 87 FRANCIS JEFFRY PELLETIER

advertisement