Document 13893571

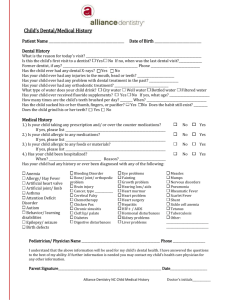

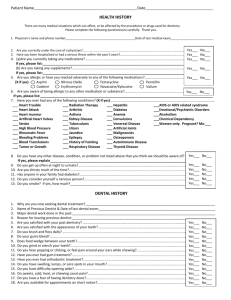

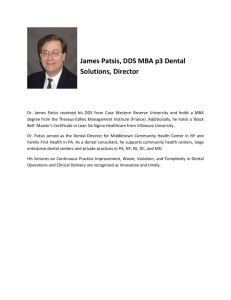

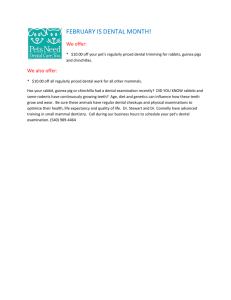

advertisement