Keepsake from a Journey to the West

advertisement

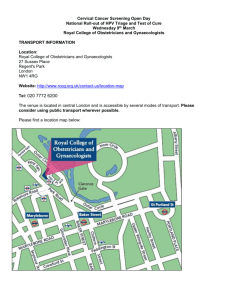

Sándor Márai Keepsake from a Journey to the West Szombathely: Helikon, 2004. English version by Owen Good We are staying opposite Regent's Park, in a close-of-the-century London house, frightfully identical to every other house in the neighbourhood; somehow being coy and of a good upbringing it doesn't differ from the others: a gentleman does not don tails when his entourage and his company wear grey day dress. Is it a pretty house? For four weeks now I don't dare look at it; I have a vague suspicion that in its outer appearance it's some ugly, Victorian construction, one part hunting lodge and one part phalansterian shack. It's an English house. […] The house is three-storeys; and there are three rooms on each storey. The kitchen, the larder, and the maids' spacious, elegant refectory are downstairs in the basement; the reception rooms and the dining room are on the ground floor, the bedrooms and guest rooms are on the two upper stories, and the maids' quarters are in the attic. An electric lift operates in the house, and the rooms upstairs lead onto a common hallway; but no room opens directly from the next, a narrow corridor, a little passage divides the rooms. You can't burst from a lodger's room directly, with sudden anger or passion, into a neighbour's: between them there always lies a little space, a strip of distance. These are they, the English people, this little dividing distance between the rooms. It's an instinct of theirs which forbids them to brush elbows with someone, even at home. There is always this little distance between rooms, between people; guests, family members live under one roof alongside one another in unnoticed isolation. The house is quiet, profoundly quiet. And the surroundings are equally free of noise, the street too. A single cat mews, some migrant, exotic cat, by no means at all an English cat, Heavens no! Nor does it belong to this house. The staff of the house deeply deplore the cat's presence and hunt it from time to time, afraid it might disturb me. To no avail I assure them that back home in Hungary I grew accustomed to even more tactless cats, more torturous mewing – I am a hardened soul, perhaps I can't be disturbed by noises and aggressions anymore. Later they catch the cat nevertheless, and after a telephone call the English Animal Lovers Association come for it, and in a chloroform box they take away the indelicate and unmannered animal. And so, there are no longer any cats in the house, the silence is absolute; undisturbed by any uninvited and foreign noises. The street is quiet too, the wide street, one bank of which is closed off by the low, emblematic iron fence of Regent's Park. All day long droves of buses and motorcars are herded along this bustling roadway, but even buses are quiet here, motorcars don't honk their horns, and I wouldn't hear a dog barking for weeks at a time. Indeed, this is silence. This is England. […] The sun is shining, and down below, on the frostbitten garden lawn of the neighbouring house a gentleman has been jumping for a quarter of an hour; I watch him and breath in my tea, this London curtsy, whose scent is full of affability and the diligent exotic; and I can't resign myself to opening the thick newspaper and staring boldly into the frightening, nightmarish grimace of the world. Holiday! – I think. – As if there were such a thing! Four weeks in which you don't have to acknowledge the world, four weeks in the seclusion of an English house… I watch the morning gymnast and envy him. I would have loved to do exercises exactly like this, every morning, in my garden. I would have loved to live so healthily. A quarter of an hour every morning with a skipping rope, then, stealing away within a world empire, a little useful work somewhere in an office or an a boat, or in an editorial, steel nerves, blonde children, a few trees in the garden, from four to six in the afternoon tennis and tea. Unfortunately none of this will ever be now. I could acquire a skipping rope – but in itself this prerequisite is not enough. I stand at the window for a long time and I watch the healthy gentleman. An idyllic silence surrounds me, in the centre of London, village tranquillity. […] At breakfast I am excused by my travelling companion: I don't need to show her London. I heave a sigh of relief, as I'm a bad explorer. From the reader, too, I now ask this exemption. We are not exploring London, we don't have the time for it, and the desire neither. A single person is more profoundly intriguing than a world city or a world empire; true, it's more difficult to explore a single person, to rove about them and to gain access to them. Perhaps the smartest thing, now, too, would be not to decide on anything in advance; let the moment plunge us between lions, museums and people, and deliver whatever it has in store for us. For the time being I will head down to Regent's Park. I have still never seen Regent's Park; there is no need to be ashamed of my ignorance, just as a Hungarian from westerly Szombathely wouldn't be ashamed of never having set foot in midland Kiskőrös. The number of London's residents surpasses Hungary's population by half a million; eight and a half million people live here, ten and a half million with the suburbs. To the people of Chelsea, Regent's Park is something similar to what the Great Plane of Eastern Hungary is to a lawyer of Győr in the North-West. One knows about it, and is proud of it, but doesn't have to see it necessarily, it isn't compulsory to get acquainted with it in this short life. True, it's a pity not to know it – it's past ten, the sun is shining, a light, fragrant vapour swims through the air, brewed from petrol, the smell of cured tobacco and the fragrance of grass and flowers, a moisture which brushes the foreigner's senses in a familiar way. Opposite the house, on the far side of the road, you cross a narrow iron bridge, and at the first corner behind the rusted cages of the zoo, Regent's Park opens out. Opens out? Appears, enters, reveals itself like an opera set the moment the curtain is pulled. You have to stop a second. ...this garden is England itself. It's what they love, that sort of spaciousness, airiness, extravagance in flat grassy fields, in lawns, in tree trunks centuries old, in slopes and arbours – a piece of salvaged England, which hasn't been gobbled up by the abhorred city, the town, felt by every Englishman as something of a prison. For them there is only one home and homeland: the country. The town is London, the beloved arch rival, the endless city, with no beginning and no end, where everything collects, and from where the Englishman must escape both figuratively and literally – he flees that which inevitably makes it a city, the metropolis' reign of terror, if by no other means, then with a family home and a symbolic patch of garden! An English person, in their heart and in their conduct, is deeply opposed to the town. This salvaged country in the middle of London is their longing for home. […] Nor is Regent's Park some unique London flora, it's a true section of the English countryside around which the town has settled. The continental man's heart always gives a leap the first time he treads upon the lawn in an English public park. I know a German writer who has lived in London for years, but in his Prussian sense of order he could never be so licentious as to trample the grass. I can, but I always have to think about it; and this kind of sense of freedom, which is deliberately practised and felt, is not real.